Introduction

March marks Neurodiversity Celebration Week (this year, 17-23 March), an annual event started in 2018 to raise awareness around neurodiversity and to help people understand, value, and celebrate the talents of those who identify as neurodivergent.

While it continues to develop, our understanding of neurodiversity has grown considerably since the term was first coined in the 1990s. One of the lessons learned from this developing awareness and understanding is the significant implications neurodiversity has in the workplace.

This article seeks to give you an initial understanding of neurodiversity, the underlying theories and models, the benefits of employing and supporting neurodivergent individuals, and ways we can better support our neurodivergent colleagues (among which, I count myself).

In this article:

What is Neurodiversity?

Sociologist and activist Judy Singer - herself diagnosed with Asperger syndrome - coined the term neurodiversity, initially as part of an effort to reduce the stigma associated with autism. Today, however, 'neurodiversity' "is...used to describe neurological differences in the human brain"1, that are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors.

Neurodiversity "takes neurological developments traditionally regarded as atypical or even as diagnosable disorders, such as autism or dyslexia, and conceptualizes them as normal human variation"2.

This includes a range of what have historically been labelled as disabilities, including autism, ADHD, dyslexia, development coordination disorder (previously known as 'dyspraxia'), dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and tic disorders (such as Tourette's syndrome). Other definitions also include other neurological differences such as those associated with mental illness, including depression or anxiety.

The UK's Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development suggests that neurodiversity can best be considered from the perspective of 'multiple intelligences' in which people function "multiple continuums of competence" and that, when talking about neurodivergent individuals, "we are talking about people who in one or several respects have a thinking style at the edges of one or more of these continuums"3.

Definitions of neurominorities

As noted above, there are some key neurominorities that are considered to fall under the neurodiversity 'umbrella'. While no two people are alike in terms of their experience and presentation of these conditions, there are broad similarities; these are briefly summarised below.

Prevalence rates

Internationally, around 10-20% of the population is estimated to be neurodivergent.

In Aotearoa, a 2022 survey undertaken by Diversity Works NZ found that 13% of the 421 respondents identified as neurodivergent. In contrast, the organisation DivergenThinking suggests "that as many [as] 40% of New Zealanders have strong neurodiverse traits". [25]

There is limited prevalence data available on the whole neurodiverse population in New Zealand, or the proportion of the neurodiverse group in the estimated 1.1 million disabled New Zealanders. The Neurodiversity in Education Coalition has estimated that around one in 5 (or 320,000) young people in New Zealand are neurodiverse.4

As the quote above illustrates, prevalence rates in Aotearoa are largely unknown.

Although prevalence estimates vary, and problems with diagnosis and identification persist, there is a shared understanding that neurodiverse individuals - whether diagnosed or not - make up a significant proportion of the population.

Underlying models

Underpinning the neurodiversity paradigm that drives the neurodiversity movement is a social model of disability.

This model takes the perspective that disabilities are "caused by the environment not being able to accommodate individuals appropriately"5 Furthermore, under this model, individuals who present with an impairment are 'differently able' and the associated disabilities are caused by "societal norms and structures"6 and the way these individuals are treated by society at large.

This approach is a direct contrast to the more traditional medical model, which treats neurodiversity (and associated diagnoses) as something that needs to be 'fixed', treated, or cured.

Consequently, impairments experienced by neurodivergent individuals are the result of a "failure of their environment to accommodate their needs."7

Based on this premise, changing the work environment to meet the physical needs of neurodivergent individuals and adjusting the cognitive and social expectations of their neurotypical coworkers should remove the impairments correlated with the neurodivergent conditions and the associated stigma.8

A strengths-based approach

As the description of the model provided above illustrates, the neurodiversity paradigm supports the view that differences in cognitive functioning are "simply differences and not deficits"9.

This position aligns with a strengths-based approach (sometimes referred to as the 'Dandelion Principle') that underpins the neurodiversity paradigm and its associated movement. This approach is seen as positive as it emphasises the positives neurodivergent people bring, while providing an opportunity to raise awareness and understanding and, in doing so, reduce stigma and discrimination.

As the chief executive of Workbridge noted in 2021: "Different doesn't mean inferior."10

From the perspective of the workplace, this should translate into a culture and approach to leadership in which businesses seek to:

identify what workers do well; and

leverage these strengths across individuals and teams' roles to meet individual and shared objectives.

Benefits of Neurodiversity

It is well-documented that diversity is important; this extends to diversity of thought and skills. Importantly, the benefits associated with diversity of thought and skills can benefit everyone, neurodiverse and neurotypical alike.

From an evolutionary perspective, humans are likely to have increased ability to adapt and survive if their population has a range of 'different brains' that have different strengths and view the world in different ways.11

Furthermore, it is important to remember "while [these conditions] definitely present challenges, they also...[bring] unique strengths and abilities".12

These unique strengths have the potential to bring a different way of thinking that "could lead to innovative solutions and give companies a competitive advantage"13, while also lifting teams' productivity, positively improving workplace culture, and boosting employees' quality of life and well-being.

As well as benefitting individuals, teams, and organisations, employing neurodivergent staff has additional 'external' benefits, particularly in organisations or businesses with a customer-facing component. Given the overall prevalence of neurodivergence, placing neurodivergent staff in roles where they are required to engage with customers ensures staff are better able to meet the needs of their customers.

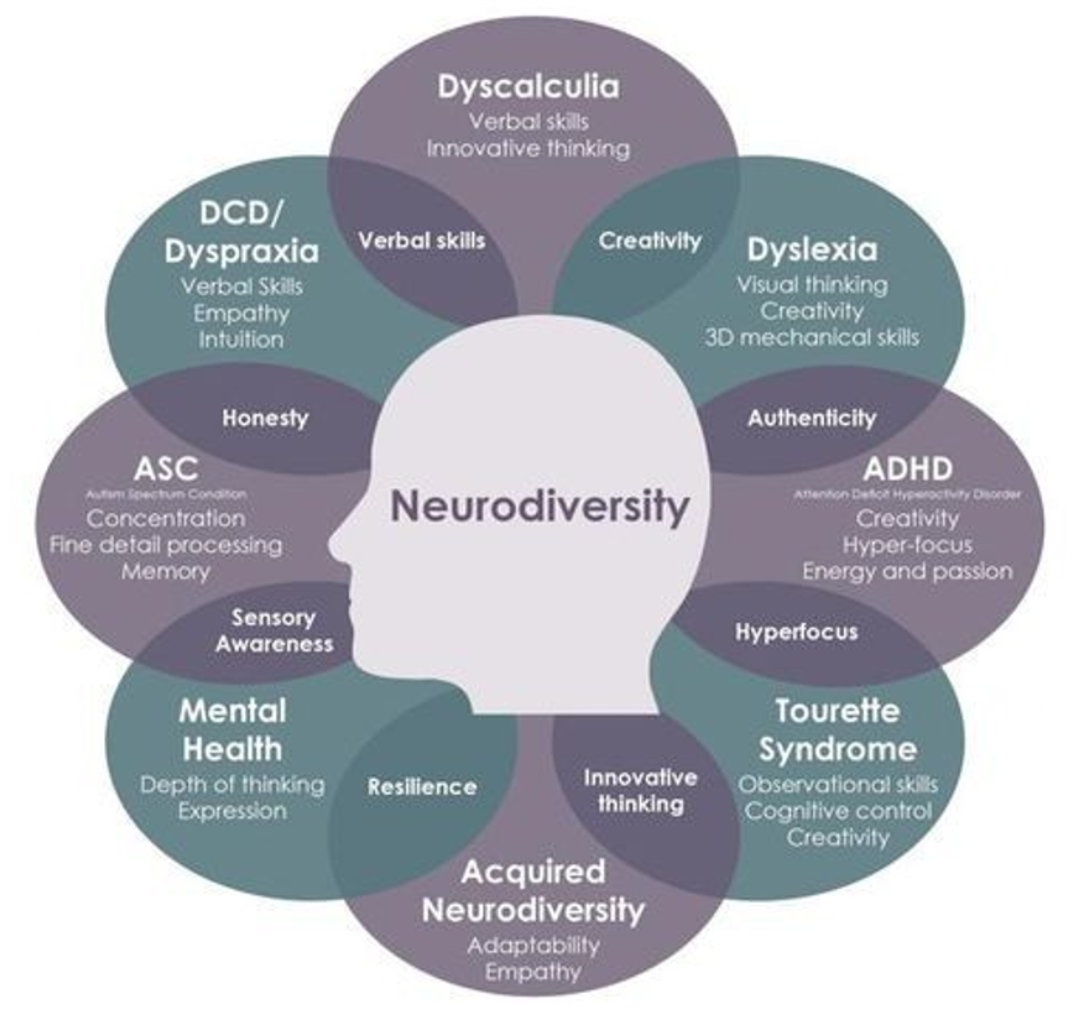

As the above image illustrates, neurodivergent individuals bring a vast range of skills that can benefit organisations, including (but not limited to):

pattern recognition and an ability to spot irregularities or inconsistencies in data

an "ability to focus on complex and repetitive tasks over a long period of time"14

high levels of creativity

high-level (often abstract) reasoning skills

a systematic and highly organised approach to work

an ability to visualise problems and solutions

bringing a unique perspective; and

highly resilient and empathetic.

An extension of this broad skill set is consideration of "the potential for neurodiverse teams to work together to deliver greater performance and innovation".15

Given the propensity for high-level analysis, creativity, and reasoning skills, among neurodivergent staff, such an approach has the potential to maximise the gains associated with hiring these individuals.

Challenges for Neurodivergent Employees

While neurodivergent staff bring a whole host of benefits, they can face several challenges in the work environment.

One of the biggest barriers for neurodivergent individuals is low levels of unemployment, with estimates indicating that as many as 50% of neurodivergent people are unemployed, as well as struggling to maintain employment because of some of the challenges discussed below.

A significant challenge in this regard is the recruitment process, with application and interview processes and psychometric testing being identified as particular barriers for neurodivergent candidates.

Another challenge for some neurodivergent workers is the sensory difficulties associated with too much noise, a high number of distractions, and other environmental effects that are often a feature of the modern workplace. As well as affecting focus and productivity, this sensory overload can lead to difficulties such as experiencing recurrent headaches and may also affect social interactions (because of the on-going strain associated with, for example, maintaining eye contact).

A common challenge for the neurodivergent is the cost associated with 'masking'. This refers to a feeling neurodivergent people have "to camouflage in social situations to appear neurotypical".16

Specific challenges for neurominorities

Some members of neurominority groups (e.g., Autistic workers) experience specific challenges at work. The not-exhaustive list below highlights some examples:

Some Autistic people may experience difficulties associated with social interactions, including struggling with 'reading' others or being misinterpreted as 'aloof' or unfriendly; this group may also struggle with time management, concentration/focus, and self-regulation.

Those diagnosed with ADHD can struggle with organisation because of becoming easily bored or distracted, and maintaining focus (e.g., in meetings); this may present as being disorganised or staying 'on topic' in conversations.

Some dyslexic workers may experience difficulties when they are expected to read/decode information quickly and may be perceived as unorganised as a result of struggles with working memory.

Neurodivergent staff diagnosed with DCD (dyspraxia) may struggle with operating machinery and/or equipment (e.g., a keyboard or mouse), as well as planning and time management.

Some staff with dyscalculia may struggle with sequencing, maths-based tasks, and/or reading and writing numbers (e.g., data entry).

Writing difficulties experienced by people with dysgraphia may affect tasks such as taking notes, copying information, or writing at pace.

The strain these challenges can place on staff, as well as the negative effects of hiding or tempering one's identity and sense of self, can have significantly negative effects on neurodivergent staff members' health and well-being.

While people living with mental illness can be considered to be neurodivergent, research suggests that some neurominorities experience higher rates of mental illness, such as depression or anxiety. This, of course, can have important implications for the health and well-being of neurodivergent staff at work.

Another challenge experienced by neurodivergent workers is a lack of awareness and understanding on the part of employers and colleagues. This can result in increased exposure to discrimination and oppression and can often lead to their difficulties being "attributed to behavioral [sic] issues or their unwillingness to 'fit in' with the other employees and [workplace] culture."17

The issue of disclosure

A particular challenge and source of anxiety for neurodivergent individuals is the decision around whether to disclose a diagnosis. Primarily, this is due to the stigma surrounding the labels of autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other cognitive variations that fall within the neurodiversity 'umbrella' and a fear of the consequences of disclosure.

It's important to be aware that, when applying for a job, an employer can ask if you have any medical problems or impairments that could affect whether you can undertake all necessary tasks to a certain standard. While you must answer such questions honestly, "you don't have to answer questions on the basis of an unlikely, worst-case scenario".18

However, an employer cannot ask "in blanket terms" about the presence of medical problems and/or impairments and cannot discriminate based on a disclosed impairment or medical condition. Finally, if you do disclose a disability, impairment, or medical condition, employers have "an obligation to take reasonable steps to accommodate a person with a disability by providing special services or facilities".19

whether you choose to disclose or not, how you do it, when, and who to, will vary based on your experience in the world. Your decision ought to be your own, and can depend on your place of employment, the kinds of people you work with and your own ideas on how to best approach the subject.20

Disclosing a diagnosis/label or neurodivergent status to an employer can have a positive effect, such as providing an opportunity to identify appropriate accommodations, strengthening relationships, or to upskill or educate leaders and colleagues.

Unfortunately, however, disclosure does not always have a positive outcome.

Consequently, it may be more positive to "rather than focus on disclosing your "label", you focus on your needs and communicate what you need to be successful and happy at work."21 The negative consequences of disclosure experienced by neurodivergent staff (e.g., discrimination and resulting poor mental health or negative effects on career progression) are most often why these staff members choose not to disclose and engage in masking behaviours.

Supporting Neurodivergent Employees

While it's important to remember that no two neurodivergent individuals are exactly alike, there are several steps organisations, employers, and leaders can take to support neurodivergent staff members.

Aside from this being the 'right' thing to do, providing such support has benefits for individuals, the teams they work in, and the business as a whole.

Previously, providing support for neurodivergent staff has been grouped into four categories: recruitment, selection, and engagement, managerial support, advocacy and policy, and accommodating individuals' needs.

Recruitment, selection, and engagement

There are several recruitment, selection, and engagement strategies workplaces can use to support staff:

Implement strategies to minimise recruiter and/or interviewer bias (e.g., eliminating applicants based on spelling errors).

Avoid including 'nice to have' skills as 'essential' components of a role.

Highlight core skills and tasks.

Provide alternative application processes (e.g., a video application).

Review interview questions and adjust accordingly, avoiding abstract questions and focussing on specific questions.

Consider providing interview questions ahead of interviews.

Avoid stereotypes, ensuring you do "not categorize people into certain skillsets based on the diagnosis"22

Ensure any engagement with neurodivergent staff is inclusive.

Ensure roles, positions, and responsibilities:

are strength-based (i.e., the skills and strengths of all employees are leveraged, rather than relying on 'generalists')

are matched to neurodivergent characteristics; and

include a degree of flexibility, allowing for role adjustments across/within a team.

Managerial Support

Leaders and managers can support neurodivergent staff by implementing a range of approaches.

Develop a people-centric style of leadership that is adopted as the default approach across the organisation.

Invest time getting to know your employees, identifying strengths and understanding needs and preferences (regardless of diagnosis or label).

Understand preferences for communication and feedback and adjust accordingly.

Role-model a "mindful approach to the different ways in which people work and communicate."23

Consider providing a mentor or 'buddy' who can advocate and support an employee.

Foster and support "a culture that offers and encourages both flexibility and inflexibility."24

Be aware of needs and preferences related to team-building and social activities (and respond accordingly).

Provide "tailored career paths that recognize [sic] the goals, capabilities, and strengths of the individual [my emphasis]"25

Advocacy and Policy

Businesses can also engage in a range of actions related to policy-setting and advocacy for neurodivergent staff.

Build a work culture that fosters acceptance and belonging and build this into organisational policies and practices.

Policies and supporting practices and processes should reflect a "mindful approach to the different ways in which people work and communicate." [15, p.4]

Build, maintain, monitor, and reward a high level of psychological safety across the organisation and within teams.

"Labels are less important than feeling safe to express your needs."26

Develop policies that support the needs and preferences of neurodivergent staff

ensure policies use clear, unambiguous language

ensure policies and procedures spell-out unspoken or assumed rules and expectations

Support neurodiversity by considering hiring targets.

Ensure any practices, policies, or initiatives take a 'for neurodivergent. by neurodivergent' approach.

Develop and provide training and education for leaders and staff on neurodiversity.

Provide access to an internal network where neurodivergent staff can exchange ideas and resources.

Ensure there are multiple options available for support and pastoral care for all staff, and that staff are aware of, and know how to access, them.

Ensure any policies and resources related to customer service are reviewed via a neurodiversity 'lens'.

Avoid a 'one size fits all' approach to advocacy, engagement, and support.

Accommodating individual needs and preferences

Alongside broader approaches, organisations need to do what they can to meet individual staff members’ needs and preferences.

It’s important to keep in mind that, while no two neurodivergent staff are exactly the same, there may be overlapping needs so, in other words, an accommodation introduced for one staff member may well benefit others.

Ensure leaders, HR, and health and safety professionals understand individual employees' needs and preferences.

Induction and training accommodations:

Ensure common activities (e.g. 'ice breakers') take account of neurodivergent needs and preferences.

Consider offering tailored one-to-one inductions.

Ensure training and development includes appropriate adjustments (e.g., sending resources in advance, providing more time for specific tasks, considering the environment in which training takes place).

See also: communication and engagement (below).

Environmental accommodations:

Consider lighting requirements, including providing neurodivergent staff access to natural light, positioning them away from bright lights, providing staff with control over lighting conditions (e.g., adjusting task-based lighting).

Consider noise levels in offices: give neurodivergent staff access to quiet work-areas and/or individual offices (without isolating them from colleagues), as well as access to noise-cancelling headphones.

Note: the latter should not be the default 'go to' solution, as they are associated with several risks to health and well-being.

Consider how shared areas can be redesigned to support the needs and preferences of neurodivergent staff.

Technological /equipment-related accommodations:

Dictation (text-to-speech and speech-to-text) software and tools.

Mind-mapping software.

Planning and memory software.

Specialised spell checkers designed for dyslexia.

Roller-ball mice.

Large-key keyboards

Ensure staff have access to resources that can support organisation and management (e.g., file trays, individual credenzas, individual notice or white boards).

Accommodations related to work-design:

Ensure autonomy for how work is undertaken and 'patterns' of work (e.g., frequent micro-breaks).

Ensure meetings take account of employees' needs and preferences (e.g., normalising standing or moving, breaking up long meetings, supporting preferences related to virtual meetings, such as leaving a camera off).

Ensure there is access to flexible work arrangements.

Ensure workload and planning requirements are transparent (e.g., ensure workflow is visible and accessible; provide greater autonomy for deciding how much work individuals can take on when).

Communicate metrics clearly - all team members should have a clear understanding of when a task or project has reached an acceptable standard or is complete.

Accommodations related to communication and engagement:

Leverage multiple modes of communication (e.g., providing accurate transcripts for multi-media).

Provide access to 'easy read' formats.

Provide instructions verbally and in writing.

Ensure processes are supported by visual aids (e.g., process maps).

Keep staff abreast of changes to plans or schedules, providing as much notice as possible as well as a reason for the change(s).

Providing templates for acceptable communiques that staff can edit (e.g., email or letter templates).

It's worth noting that many of the support mechanisms listed above overlap with the characteristics of mentally healthy work defined by WorkSafe. Providing this type of work is a legislative requirement under the Health and Safety at Work Act (2015).

Consequently, it's important workplaces provide the necessary support to neurodivergent employees, to ensure obligations are being met.

Key Principles

As this article has illustrated, the topic of neurodiversity is a complex one, but there are some key principles you can try to remember:

Neurodivergent people are not 'abnormal" or disabled; they have a type of cognitive functioning that is different from the 'typical'. In this way, neurodivergence is the same as other forms of diversity - such as ethnic or gender-based diversity - and, consequently, these differences have immense value and deserve respect and care.

Just like implementing universal design into workplace design, improving workplaces for neurodivergent staff will have benefits for ALL staff.

Businesses and organisations should aim to understand underlying diagnoses, while also recognising that "each individual is unique...and that each person needs to be accepted and accommodated differently."27

To support neurodivergent staff, workplaces "must apply curiosity, look past the hurdles flagged by our biases and cultural constructs, and see the potential in a neurodivergent employee."28

The key to supporting and including neurodivergent staff at work is to use a person-centred, strength-based approach characterised by kindness, manaakitanga, patience, and aroha.

When working with neurodivergent staff, it is vital you: "listen to them... believe them... and remember that support is more important than understanding"29

Bibliography

ADDitude (n.d.). Learning Disabilities

Aston University (2020). Neurodiversity Guide

Bainbridge, H. (n.d.). Reveal or conceal? The pros and cons of disclosure in the workplace.

Barnes, M. (2022, September 13). Masking: What is it and why do Neurodivergent People do it?

Burton, L., Carss, V., & Twumasi, R. (2022). "Listening to Neurodiverse Voices in the Workplace". Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture, 3(2), 56-79.

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2018). Neurodiversity at Work. CIPD: London, UK.

Community Law (2022, August 22). Employment: Access to Jobs and Protection Against Discrimination.

Day-Duro, E., Brown, G., & Thompson, J. (2020). Thinking Differently: Neurodiversity in the Workplace. Hult Ashridge: Hertfordshire.

Deloitte Center for Integrated Research (DCIR) (2022). A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats: Creating a Better Work Environment for All by Embracing Neurodiversity

Disabled World (2022, November 29). What is: Neurodiversity, Neurodivergent, Neurotypical?

DivergenThinking (2022, April 11). What is Neurodiversity?

DivergenThinking (2021, September 23). Neurodiversity in New Zealand

Diversity Works (2022). New Zealand Workplace Diversity Survey 2022. Diversity Works NZ: Auckland, NZ.

Doyle, N. (2020). 'Neurodiversity at Work: A Biopsychosocial Model and the Impact on Working Adults'. British Medical Bulletin, 735, pp.108-125. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldaa021

Fitzgerald, J. [Editor] (2022). Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand: Short Essays on Important Topics. Worksafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

Harris, K. (2021, August 30). Autism, ADHD, and Dyslexia: How Workplaces can Help Neurodiverse Workers Thrive

Houdek, P. (2022). 'Neurodiversity in (Not Only) Public Organizations: An Untapped Opportunity?' Administration & Society, 54(9), 1848-1871. https://doi.org/10.1177/00953997211069915

Kirby, A. (2021). Where Have All the Girls Gone? Neurodiversity and Females. Do-IT Solutions Limited: Cardiff, Wales.

Knowsley, A. (2018, August 9). Disability in the workplace: What rights do employees have?

Krzeminska, A., Austin, R. D., Bruyere, S., and Hedley, D. (2019). "The Advantages and Challenges of Neurodiversity Employment in Organizations". Journal of Management and Organization, 25, pp. 453-463. doi:10.1017/jmo.2019.58

Marshall, B. A. (2022). Workplace Neurodiversity: An Exploratory Study [Dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Business Administration]. Alliant International University: San Diego, CA.

Ministry of Health (MoH) (2024, March 18). Briefing: Overview on Neurodiversity.

Morgan-Trimmer, R. (2020, August). What is Neurodiversity and Why Should You Care About It?

National Health Service (2021, November 18). Conditions: Tics.

Price, A. (2022, February 15). Neurodiversity and the Workplace.

Russell, A. (2022, May 12). The Neurodiversity Gap in our Workplaces.

Skellig, J. (2020, June 9). Neurodiversity: An Overview.

Stallings, B. (2023, February 13). Here are Six Practices to Support Neurodiversity at Work and Home.

Umbrella Wellbeing (2021, March 25). Neurodiversity in the Workplace: Different not Less.

Walker, M. [Host] (2023, March 9). 'Episode 6: Neurodiversity Part 1' [Audio podcast episode]. In Working Well.

Walker, N. (2021, August 1). Neurodiversity: Some Basic Terms and Definitions

Whelpley, C. P., Holladay-Sandidge, H. D., Woznj, H. M., & Banks, G. C. (2023). 'The Biopsychosocial Model and Neurodiversity: A Person-centered Approach'. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16, 25-30.

Worksafe (2021, July 8). Mentally Healthy Work.

World Economic Forum (2022, October 10). Explainer: What is Neurodivergence? Here's What You Need to Know.

Skellig (2020, p.1).

Krzeminska et al. (2019, p.453).

CIPD (2018, p.7).

MoH (2024, p.3).

Whelpley et al. (2023, p.25).

Burton, Carss, & Twumasi (2022, p.56).

Marshall (2022, p.11).

Ibid.

Skellig (2020, p.3).

Harris (2021, online).

Kirby (2021, p.1)

Morgan-Trimmer (2020, online).

DCIR (2022, p.2).

Price (2022, p.3).

CIPD (2018, p.11).

Barnes (2022, online).

Marshall (2022, p.26).

Community Law (2022, online).

Knowsley (2018, online).

Bainbridge (n.d., p.5).

Umbrella Wellbeing (2021, p.4).

DCIR (2022, p.8).

Price (2022, p.4).

DCIR (2022, p.10).

Ibid, p.12.

Umbrella Wellbeing (2021, p.3).

Whelpley et al. (2023, p.28).

Stallings (2023, p.7).

Walker (2023, podcast episode).