Supporting Workers' Health and Safety via Workplace Design: Part 2

The second in a three-part series exploring how businesses can support workers' health, safety, and well-being via the design of the workplace

Introduction

The environmental conditions of a workplace are a key element of workplace design shown to affect workers’ health, safety, and well-being. Acoustics and noise, privacy, ergonomics, temperature, air-quality and ventilation, lighting, the number of distractions, aesthetics and colour design, furniture choice, space allocation and availability, IT resources and storage space have all been associated with workers’ overall health and well-being, job satisfaction, and productivity.

In Aotearoa, the national regulator - WorkSafe - sets out minimal requirements for workplaces and associated facilities, noting they “must be clean, healthy, safe, accessible and well maintained so work can be carried out without risks to worker health and safety.”1

As we’ve explored before, the way an office is designed and laid out can constitute a risk that may affect a worker’s health and, as a potential cause of stress, can be defined as a psychosocial hazard or risk.

A habitability model

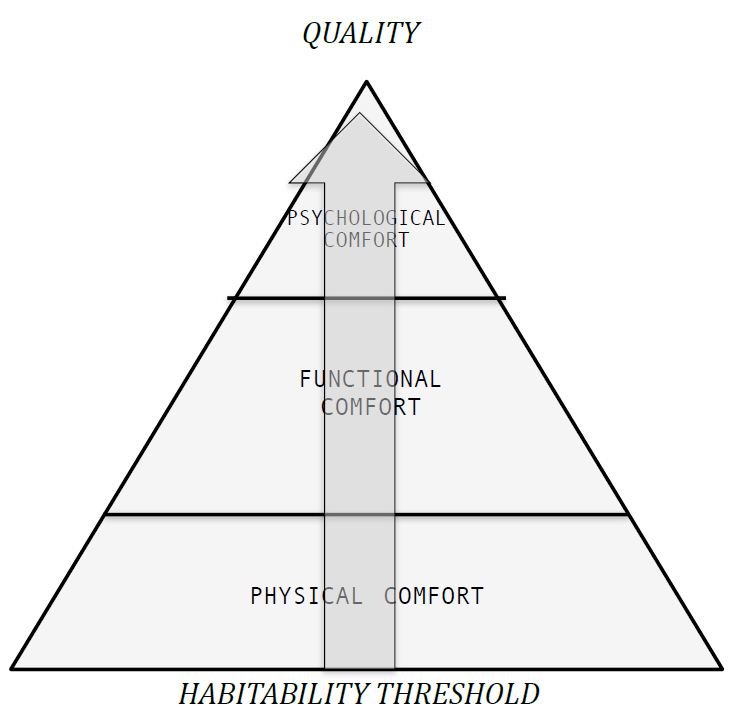

For some scholars, the physical workplace is considered a feature of ‘quality of work life’ (QWL) that, in turn, is a sub-category of overall quality of life. From this perspective, a poorly designed workplace results in a lower QWL, increasing workers’ stress. Therefore, this increases the risk of negative health outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, job dissatisfaction, and poor organisational outcomes, such as lower productivity and higher rates of absenteeism and presenteeism.

For these authors, habitability is an important concept in workplace health and safety.

‘Habitability defines the degree of fit between individuals or groups and their environment, both natural and man-made, in terms of an ecologically sound and humane, built environment’ (Preiser op.cit.). Habitability requires that the physical environment meet three categories of users’ needs: health and safety, functional and task performance, and psychological comfort. Improving habitability through a better fit between the occupant and the workspace means a better quality work environment and improved QWL.2

Working with these three levels of habitability, Vischer proposed a habitability model comprised of:

Physical comfort - the minimum health and safety requirements for workplace design, such as safe access or resources to support personal hygiene.

Functional comfort - a continuum of design elements that affect how well a worker can undertake the tasks associated with their role, such as lighting, acoustics, privacy, or ventilation.

Psychological comfort - the elements of design that support territoriality or a sense of belonging, privacy, and a sense of control.

According to this model, although a deficit in one area can be compensated by another, optimal workplace design is achieved “when workspace quality is assured at all three comfort levels.”3

As this model illustrates - along with WorkSafe’s requirements and a definition of a healthy workplace used by the WHO - environmental quality is essential to workers’ health, safety, and well-being.

Effects on workers

Not surprisingly, environmental conditions can have a range of positive and negative effects on workers.

Mental health and well-being at work has been shown to be significantly affected by the quality of the office environment. Conditions including lighting, thermal comfort, air quality and ventilation, acoustics, colour, and comfort of furnishings have all been shown to affect workers’ psychological and psychosocial well-being.

Workplaces’ environmental quality has been identified as an important consideration for productivity. Employees’ productivity has been shown to be affected by:

thermal comfort

air quality

exposure to daylight

the ability to control lighting

access to nature

noise, acoustics, and distractions

privacy; and

space allocation, including breadth of available spaces.

Similarly, environmental conditions have been shown to affect job satisfaction. Such conditions include increased noise and distractions, reduced privacy, and higher demands on cognitive load caused by poor environmental design.

The work environment significantly influences employee satisfaction… [with elements] such as space, physical layout, noise, tools, materials, and relationships…all play[ing] a crucial role.4

As noted in Part 1, these effects can sometimes be experienced differently by different groups.

Female employees have been shown to be, in general, more dissatisfied with environmental conditions, especially poor ventilation and higher levels of noise.

Older workers have also been found to be less satisfied with the work environment than their younger colleagues, and - not surprisingly - also feel the negative effects of noise more acutely.

Some personality characteristics, such as introversion, have been shown to be associated with a preference for quieter work environments.

In addition, staff with disabilities are a key consideration. Under current legislation in Aotearoa, employers are required to provide a workplace that takes account of all workers and their views, needs, and preferences.

While individual employees will have individual needs and preferences, common traits/presentations of some disabilities can be used to help guide design decisions. The ability to concentrate or maintain focus, for example, is commonly seen among those living with ADHD, design strategies such as ensuring there are quiet or focus spaces available, supported by appropriate use of lighting and colour can be applied.

In addition, general resources - such as MBIE’s Building for Everyone: Designing for Access and Usability resource - can be used to support the health and safety, and, by extension, well-being, of all workers.

Environmental considerations

As noted above, there are several different elements of the workplace environment businesses should consider.

Comfort

Although it is a complex, multi-faceted construct, employees’ physical comfort is a key consideration in workplace design.

While research has yielded mixed results, it consistently identifies a link between a poor work environment and negative effects on workers’ physical and psychosocial health, ability to concentrate, and productivity, which, in turn, affects their job satisfaction and overall well-being.

Comfort has been shown to be problematic in so-called modern ways of working.

Hot-desking has been shown to negatively influence workers’ physical health in terms of ergonomics.

Comparative research found that “ABW office occupants had the highest physical discomfort in shoulder, lower back, and wrist/hand regions.”5

This may be related to an inability to personalise ergonomic design of workstations, further underscoring the need to consider desk allocation.

An increasingly prevalent feature of flexible offices is the use of sit-stand desks.

A Japanese randomised controlled trial found that, although no effects were seen in relation to improving participants’ BMI or lower back pain, “participants’ subjective view of their health improved, and they reported that pain in their neck and shoulders was reduced compared to before the intervention”6.

While the evidence in support of these devices is mixed, some research indicates positive outcomes in terms of workers’ physical health and well-being, as well as a higher level of satisfaction with the office environment.

Noise and acoustics

Noise is a feature of workplace environments that is frequently identified as an area of concern, especially in office and similar ‘white collar’ environments. However, noise is problematic for a wide range of work environments, including, for example, hospitality, retail, construction, and manufacturing settings.

As noted in Part 1 of this series, open-plan and ABW designs is a significant issue for people working in these environments. Importantly, research has demonstrated that the effects of noise and distractions are enduring for those working in these environments.

If unmanaged, employees may be exposed to an increased risk of hearing loss which, according to WorkSafe “has health impacts including reduced productivity, feelings of isolation and exclusion, stress and fatigue”.7

Workers’ exposure to unwanted noise, and inability to control noise levels, in their environment can have several negative effects. This includes:

a loss of productivity and decreased performance

decreased job satisfaction

negative effects on work relationships, including increased workplace conflict

reduced collaboration and engagement

decreased cognitive functioning – such as effects on workers’ “reaction time, decision making, learning, and memory”8; and

a direct effect on employees’ health and well-being.

An associated issue is that of increased experience of distractions, not only from background office noise (for example, air conditioning units), but also from colleagues’ conversations/discussions and social interactions. These have been shown to have similarly debilitating effects on workers’ health and well-being. In open-plan offices, especially, distractions “can challenge concentration, leading to increased stress and poorer health and social dynamics.”9

As noted above, a key effect of noise - and distractions - at work is the increased cognitive demand placed on staff. These effects have been shown to be linked to increased instances of fatigue among workers, as the cognitive load associated with managing the environment increases. Other research suggests that increased noise and distractions leads to a decrease in the ability to concentrate, negatively affecting workers’ satisfaction, motivation, and general health and well-being.

Noise in open-plan and ABW environments has also been identified as a barrier for staff in terms of establishing a sense of belonging, often via the decreased communication and engagement that occurs. One reason for this is that, in an effort to reduce distractions and noise for others, workers stop initiating conversations, limiting the ‘casual’ and incidental interactions that take place.

Speech intelligibility has often been shown to be an issue, with studies indicating that low intelligibility (for example, whispered conversations) are often more distracting and disruptive for staff. In addition, as workers use whispering as a way of minimising noise, it can negatively affect workplace culture, acting as a potential source of conflict as staff become suspicious of why their colleagues are whispering to each other.

A particular issue associated with noise at work is the lack of control staff have. While resources such as PPE (e.g., ear plugs) can be used to combat some of the effects of noise, workers largely have no control over how much noise - and distractions - they are exposed to, further exacerbating the ill effects of noise and poor acoustic design.

However, although often cited as an area of concern for workers, it is sometimes ‘trumped’ by other environmental concerns. Recent research has offered results identifying that workers place “a lower rank [on] the importance of privacy and noise level.”10

Privacy

A lack or loss of both auditory and visual privacy has been shown to negatively affect workers’ health and well-being; it is a repeatedly cited disadvantage of the open-plan and ABW approaches to office design.

Lower auditory and/or visual privacy in the workplace has a number of negative effects on workers’ health, safety, and well-being. These include:

negatively affecting relationships with colleagues

increased demands - especially cognitive demands - on workers; and

general negative effects on workers’ psychological and psychosocial well-being.

A 2013 analysis highlighted the loss of auditory privacy – the ability to have a conversation without others overhearing it – as the biggest complaint for those in open-plan offices.

The presence or absence of privacy in the workplace has also been linked to job satisfaction, with research demonstrating “that talk privacy has a significant relationship with job satisfaction”11.

Recent work identifies privacy “as a crucial element in an employee’s comfort and their capacity to perform tasks that require deep concentration”12 and notes that traditional open-plan workplaces yield low privacy ratings, suggesting they yield less positive outcomes.

Alongside ensuring other positive environmental conditions, such as access to nature, organisations that ensure privacy for staff are shown to reduce stress and improve mental health outcomes.

Temperature

Workplaces need to be designed to provide a temperature that facilitates a healthy working environment, ensuring, wherever practicable, the climate is not too hot or cold.

While there are a range of environmental and personal factors that can affect the temperature in an office, thermal discomfort has been associated with negative effects on workers’ motivation, mood, and general well-being, and - as a result - lower rates of productivity.

Temperatures below or above 20–24oC and a relative humidity below or above 40–55% could decrease an individual’s productivity, concentration, sleep quality, mood, and well-being, and increase fatigue and stress.13

Similarly, in laboratory experiments, higher temperatures – 28oC – have been linked to workers’ experience of negative mood.

Other work has highlighted that while workers are able to maintain their performance in thermally uncomfortable environments, doing so takes considerable effort, resulting in perceptions of higher workload and fatigue.

Recently, longitudinal research from the UK identified a 21.54oC as an optimal temperature for the workplace.

Lighting

Designing lighting to support workers’ health and safety is another important factor in the workplace.

Inadequate lighting is often cited as a key issue for workers’ health and well-being at work and has been linked to employees’ physical and mental well-being. In offices, research looking at a transition from cellular offices to an open-plan and ABW design highlights concerns around lighting, including a lack of natural lighting, with these concerns persisting around two years post-move.

Workers “with the shortest daily exposure time to high light levels reported the lowest mood… and the daily light dose received by people in industrialized [sic] societies might be too low for good mental health”14.

A key consideration here is perception: a comparison of subjective and objective measurement of light and its effect on mood identified negative effects for the former (when lighting was too dark or bright), but none for the latter.

However, ensuring staff have access to appropriate lighting is identified in the research as an important environmental factor that acts as a driver for workers’ decision-making around seat/location-selection.

Providing workers with access to natural light or ‘daylighting’ has been called out as key to supporting employees’ productivity, well-being, and overall mood. Other work indicates a lack of access to natural light is related to depressive symptoms and a lower sleep quality.

Current standards in Aotearoa advocate a light level of 300-500 lux for general office work, with lower levels for walkways/circulation spaces (c.100-200lx) and meeting rooms (300lx); tasks requiring fine detail-work (e.g., proof-reading/editing, reviewing plans or drawings, or process mapping on screens) require higher levels (600lx).

Air quality

Air conditioning systems have an essential role in providing an appropriate air quality for workers. If poorly controlled, air quality and unsuitable ventilation in the office can be a potential hazard for workers (for example, spreading pollutants, bacteria, or viruses).

Research identifies indoor air quality as a key predictor of comfort, health, and productivity, particularly in open-plan offices. Various work draws attention to the link between poor air quality/ventilation and workers’ mental health, including increased stress and fatigue.

High levels of carbon dioxide can indicate an increased risk of exposure to viruses such as COVID-19. A particular consideration here is the use of closed meeting rooms, in which CO2 levels can rise over time, increasing the risk of exposure for workers.

The risk of ‘sick building syndrome’ symptoms increases progressively when CO2 [levels] rises above 800 ppm… [research findings show] that cognitive performance and decision-making abilities are highest when CO2 concentrations are at 600 ppm, and progressively deteriorate at higher concentrations”15.

Access to nature

Giving workers access to outdoor views, as well as encouraging accessing outdoor areas directly (for example, going for walks in nature) has been shown to:

have a mediating effect on distractions in the office

reduce stress

increase job satisfaction

foster productivity

have a restorative effect for workers; and

improve overall health and well-being.

[The] impact of windowless environments [show] a direct link between the lack of windows in workplaces and negative outcomes like job dissatisfaction, feelings of isolation, depression, tension, and claustrophobia.16

However, for some researchers, providing a view is not enough as “quality of views is important [as well as] placement of desks to avoid negative consequences from glare and uncomfortable temperatures”17.

In contrast, others suggest that “studies have consistently shown that building users prefer having access to windows and views regardless of the quality of the view [my emphasis]”.18 Granting staff access to views and windows, it is argued, offers psychological, emotional, social, and physiological benefits, and is considered important to workers’ satisfaction with and comfort in the workplace.

As well as views, giving staff access to nature inside the workplace is shown to be beneficial for workers. The addition of biophilia/plants in the workplace, research suggests:

increases productivity

improves concentration

increases workers’ creativity

reduces stress

reduces incidence of mental illness (e.g., depression)

lifts overall health and well-being; and

acts as a ‘buffer’ or resource to help cope with job demands.

Layout

As we discussed in Part 1, the way a workplace is laid out is a major consideration for safe and healthy workplace design. Careful consideration of layout requirements can have an important effect on health and well-being via their influence on team effectiveness, job satisfaction, and productivity.

Zoning and layout are especially important considerations for ‘modern’ office environments. In open-plan and ABW environments, researchers have identified several issues, including:

not providing enough desks, meeting rooms, or ‘break-out’ areas

placing quiet zones too close to collaboration zones and/or circulation spaces

poor ergonomic design of different work zones

providing furniture and design elements in quiet/focus zones that encourage conversations

not making different zones visually distinctive (making it difficult for staff to interpret the intended use); and

a lack of behavioural guidelines or ‘rules’ in place to support zoning and signage/information to communicate the same.

Such poor design decisions can exacerbate other problems - in particular, negative effects of noise/poor acoustics. Similarly, to avoid errors like those listed above, leaders need to engage in analysis to understand requirements for tasks and the needs and preferences of teams and individuals.

Collaboration

Workplaces need to be designed so they strike a balance between facilitating work, supporting social connections/interactions, and building and strengthening team and organisational identities.

Previously, research has pointed to layout as a significant predictor “of perceived support for collaboration”19, supporting the need for careful design when collaboration and engagement between staff is important to a business or team.

When people can work near direct colleagues, it is argued, their health and well-being is improved, alongside positive effects on relationships between managers and their direct reports. This needs to be balanced against individuals’ personal space boundaries as, when breached, colleagues working too close or too far away from staff increases individuals’ discomfort.

In addition, while improvements in communication and collaboration can be beneficial, noise, acoustics, and privacy considerations are vital to decision-making related to how closely workers should be placed together.

A final consideration - especially in modern office environments - is the flexibility of layout.

Given the importance of collaborative problem-solving, organizations need dedicated spaces with flexible furniture arrangements and technologies to facilitate the exchange of ideas and promote innovative thinking.20

Other environmental considerations

Aesthetics and furnishings

Previous work identified aesthetics, furnishings, and the ability to adapt work areas as being highly ranked in participants’ perceptions of productivity, health, and comfort, suggesting a clear need for careful planning of these design elements. Similar results have also been found in relation to employees’ level of satisfaction with the comfort of furnishings.

A series of interviews with Swedish consultants, for example, revealed that, while not necessarily a deciding factor in choosing where to work, “[when] elaborating on the interior design of their office spaces, many [participants] express they experience a pleasant feeling to work in a well-designed office.”21

Similarly, various authors identify workplace aesthetics as important for workers’ mood, productivity, and job satisfaction.

Cleanliness

Research has highlighted the importance of cleanliness, both as a predictor for worker productivity and as a tool to minimise the risks associated with the spread of infection.

In Aotearoa, at least, there is a clear requirement for workplaces to provide a level of cleanliness that protects and promotes workers’ health and safety. This is an element that has received considerable emphasis in recent years, in the onset and aftermath of the COVID-19 global pandemic.

Colour

Another element of the office environment is colour selection; this has been linked to people’s behaviour, health and well-being, and productivity.

While colour-coding is important for identifying risks and hazards in the workplace, colour-selection has been shown to influence physical health (for example, reducing eye- strain), mood, and mental well-being.

IT Resourcing

While not an environmental or ambient design consideration per se, providing appropriate IT supports, especially in office environments, is identified as a key consideration.

The provision of IT resources and supports has been shown to be important for both implementation of new workplace designs and the day-to-day operationalisation of the same designs. Importantly, not providing such resources can make a bad workplace design worse for some workers.

Such resources can include, but is not limited to:

ensuring there are enough power sockets provided

digital directories that allow workers to easily find each other

digital sign-in tools

robust (and consistently working!) Wi-Fi connections

effective, easy-to-use, booking tools

‘follow me’ printing services; and

robust, effective video conferencing tools.

Environmental control

The environmental considerations discussed above form the physical and functional comfort levels of Vischer’s habitability model. In other words, they are the foundation upon which a safe and healthy workplace design rests.

As discussed at the start of this post, psychological comfort is a third element that is equally essential for workers’ health, safety, and well-being. We explored the notion of belonging in Part 1 of this series. In particular, the use of hot-desking has been called out in the literature as a key detractor in helping workers form a sense of belonging and cultivate their identity at work.

A second element of psychological comfort is environmental control. This is a key component of giving workers autonomy and is, therefore, an essential component of mentally healthy work.

Possibly, the most effective way of optimizing environmental comfort will be to allow employees to adjust local conditions to their own preferences, instead of attempting to satisfy all occupants with the same configuration of [indoor environmental quality] [sic].22

Similarly, giving employees control over their environment can act as a key coping mechanism that can mitigate the effects of stress associated with a change in office design. Some research, for example, demonstrates improvements in workers’ thermal comfort following the introduction of individualised controls for temperature.

The ability to adjust chairs, desks, and screens, personalise their desk, open and close doors, rearrange furniture (for example, moving tables), adjust lighting, and create “micro-climates” is shown to have a positive effect on physical and psychological well-being. As noted above, the application of ‘modern’ workplace design benefits immensely from flexible design, such as being to adjust different design elements to support different ways of collaborating.

Different workers “prioritize [sic] and attend to different features of the environment, and the easier one can adjust and control their environment, the easier they can adapt”23

Just as how a workplace is designed can support or undermine workers’ health and well-being, the environmental conditions in the workplace have the potential to have a massive influence on individual workers, teams, and organisations as a whole.

Leaders, business owners, and workplace designers need to pay careful attention to environmental conditions such as lighting, ventilation, acoustics, colour, and furniture choice. If they don’t, they risk putting their workers in harm’s way and, ultimately, affecting their own success.

Part 3 of this three-part series will explore interventions and recommendations for implementation.

Bibliography

Ahlberg, D., & Blomberg, A. (2024). "I want to socialize at the office, but I'll quit if forced to be there": A Qualitative Case Study on Belongingness of Junior Consultants in Hybrid Work Environments (Dissertation). Retrieved from https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-232280

Alsarraj, H. A. (2019, July). Open-plan Office and its Impact on Interpersonal Relationships [Master’s Thesis]. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University of Technology.

Andrews, D. C. (2016). A Space for Place in Business Communication Research. International Journal of Business Communication, 54(3), 325-336. doi:10.1177/2329488416675842

Appel-Meulenbroek, R., Voordt, T., Aussems, R., Arentze, T., & Le Blanc, P. (2020). Impact of Activity-based Workplaces on Burnout and Engagement Dimensions. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 22(4), 279-296. doi:10.1108/JCRE-09-2019-0041

Ayoko, O. B., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2020). The Physical Environment of Office Work: Future Open Plan Offices. Australian Journal of Management, 45(3), 488-506. doi:10.1177/0312896220921913

Babapour, M. (2019). The Quest for the Room of Requirement: Why some Activity-based Flexible Offices Work While Others Do Not [Doctoral Thesis]. Gothenburg, Sweden: Chalmers University of Technology.

Babapour Chafi, M., Harder, M., & Danielsson, C. B. (2020). Workspace preferences and non-preferences in Activity-based Flexible Offices: Two Case Studies. Applied Ergonomics, 83, 102971.

Bergsten, E. L., Wijk, K., & Hallman, D. M. (2022). Implementation of Activity-Based Workplaces (ABW): The Importance of Participation in Process Activities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14338.

Bernstein, E., & Turban, S. (2018). The Impact of the 'Open' Workspace on Human Collaboration. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1753), 20170239.

Bodin Danielsson, C., & Theorell, T. (2024). Office Design’s Impact on Psychosocial Work Environment and Emotional Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 21, 438

Buick, F. et al. (2024). Adopting a Purposeful Approach to Hybrid Working: Integrating notions of place, space, and time. Policy Quarterly, 20(1), 40-49

Burton, J. (2010). WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Budie, B., Appel-Meulenbroek, R., Kemperman, A., & Weijs-Perree, M. (2019). Employee Satisfaction with the Physical Work Environment: The Importance of a Need-based Approach. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 23(1), 36-49. doi:10.3846/ijspm.2019.6372

Candido, C., Chakraborty, P., & Tjondronegoro, D. (2019). The Rise of Office Design in High- performance, Open-plan Environments. Buildings, 9(4). doi:10.3390/buildings9040100

Candido, C., Gocer, O., Marzban, S., Gocer, K., Thomas, L., Zhang, F., & ...Tjondronegoro, D. (2021). Occupants' Satisfaction and Perceived Productivity in Open-plan Offices Designed to Support Activity-based Working: Findings from Different Industry Sectors. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 23(2), 106-129. doi:10.1108/JCRE-06-2020- 0027

Candido, C., Marzban, S., Haddad, S., Mackey, M., & Loder, A. (2020). Designing Healthy Workspaces: Results from Australian Certified Open-plan Offices. Facilities, 39(5/6), 411-433. doi:10.1108/F-02-2020-0018

Colenberg, S., Appel-Meulenbroek, R., Romero Herrera, N., & Keyson, D. (2021). Conceptualizing Social Well-being in Activity-based Offices. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(4), 327-343. doi:10.1108/JMP-09-2019-0529

Colenberg, S., Jylhӓ, T., & Akesteijn, M. (2021). The Relationship Between Interior Office Space and Employee Health and Well-being - A Literature Review. Building Research and Information, 49(3), 352-366. doi:10.1080/09613218.2019.1710098

Cu, A. (2024). Does space matter? An exploratory study of the effects of workplace settings on the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness [Thesis for MA (Psychology)]. Auckland University of Technology.

Forooraghi, M., Cobaleda-Cordero, A., & Babapour Chafi, M. (2022). A Healthy Office and Healthy Employees: A Longitudinal Case Study with a Salutogenic Perspective in the Context of the Physical Office Environment. Building Research and Information, 50(1- 2), 134-151.

Gauer, S., & Ilic, L. (2023). Leadership in Multi-space Offices: Realizing the Potential of Modern and Flexible Workplace Concepts. IntechOpen, doi: 10.5772/intechopen.106887

Geldart, S. (2022). Remote Work in a Changing World: A Nod to Personal Space, Self- regulation and Other Health and Wellness Strategies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4873). doi:10.3390/ijerph19084873

Gerlitz, A., & Hülsbeck, M. (2023). The Productivity Tax of New Office Concepts: A Comparative Review of Open-plan Offices, Activity-based Working, and Single-office Concepts. Management Review Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00316-2

Gillespie, K. (2019, April 11). Open-plan, Hot-desking...The Fast-track to Poor Well-being and Performance. Retrieved from: https://www.glwswellbeing.com/working/open-plan-hot-desking-the-fast-track-to- poor-wellbeing-performance/

Government Property Group. (2020, April 28). Principles for Office Design. Retrieved from Workplace Design Guidelines: https://www.procurement.govt.nz/property/workplace-design-guidelines/principles-for-office-design/

Haapakangas, A., Hallman, D. M., Mathiassen, S. E., & Jahncke, H. (2019). The Effects of Moving into an Activity-based Office on Communication, Social Relations, and Work Demands - A Controlled Intervention with Repeated Follow-up. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 66(101341). doi:10.1016/j.envp.2019.101341

Haapakangas, A., Hallman, D. M., & Bergsten, E. L. (2023). Office design and occupational health–has research been left behind? Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 49(1), 1.

Hancock, F. (2022, July 11). Whose Breath are You Breathing? Retrieved from https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/in-depth/470690/whose-breath-are-you-breathing

Harb, F., Hidalgo, M. P., & Martau, B. (2015). Lack of Exposure to Natural Light in the Workspace is Associated with Physiological, Sleep, and Depressive Symptoms. Chronobiology International, 32(3), 368-375. doi:10.3109/07420528.2014.982757

Healey, N. (2020, February 17). Hot-desking Was Meant to Save Us All Time and Money. It Hasn't. Retrieved from: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/hot-desking-meaning-benefits

Hirst, A. (2011). Settlers, Vagrants, and Mutual Indifference: Unintended Consequences of Hot-desking. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(6), 455-473. doi:10.1108/09534811111175742

Hodzic, S., Kubicek, B., Uhlig, L., & Korunka, C. (2021). Activity-based Flexible Offices: Effects on Work-related Outcomes in a Longitudinal Study. Ergonomics, 64(4), 455-473. doi:10.1080/00140139.2020.1850882

James, O., Delfabbro, P., & King, D. L. (2021). A Comparison of Psychological and Work Outcomes in Open-plan and Cellular Office Designs: A Systematic Review. SAGE Open, 11(1), 1-13. doi:10.1177/2158244020988869

Kamarulzaman, N., Saleh, A. A., Hashim, S. Z., Hashim, H., & Abdul-Ghani, A. A. (2011). An Overview of the Influence of Physical Office Environments Towards Employees. Proceedia Engineering, 20, 262-268.

Kim, J., & de Dear, R. (2013). Workspace Satisfaction: The Privacy-communication Trade-off in Open-plan Offices. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 18-26.

Kim, J., Candido, C., Thomas, L., & de Dear, R. (2017, July). Desk Ownership in the Workplace: The Effect of Non-territorial Working on Employee Workplace Satisfaction, Perceived Productivity, and Health. Building and Environment, 103(July), 203-214. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.04.015

La Brijn, D., Houtveen, S., & Schlangen, J. A. (2022, September). The role of cohesion and connection within the ABW framework: A critical elaboration. Paper presented at the 3rd Transdisciplinary Workplace Research Conference, Politecnico di Milano, Italy.

Langer, J. (2021, June). The Impact of the Physical Office Environment on Occupant Wellbeing. [Doctoral Thesis]. Cardiff, Wales: School of Psychology, Cardiff University.

Langer, J., Smith, A., & Taylour, J. (2019). Occupant Psychological Wellbeing and Environmental Satisfaction After an Open-plan Office Redesign. In R. Charles, & D. Golightly, Contemporary Ergonomics and Human Factors (pp. 223-233). Warwickshire, UK: Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors.

Ma, J., Ma, D., Li, Z., & Kim, H. (2021). Effects of Workplace Sit-Stand Desk Intervention on Health and Productivity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11604.

Mache, S., Servaty, R., & Harth, V. (2020). Flexible Work Arrangements in Open Workspaces and Relations to Occupational Stress, Need for Recovery, and Psychological Detachment from Work. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 15(1), 1- 11.

Mateescu, M., Schulze, H., & Kauffeld, S. (2024). Choosing where to work: an empirical study of collaborative activities’ impact on workspace choice behavior. Journal of Corporate Real Estate.

MBIE. (2022). Practical Application of Universal Design. Retrieved from: https://www.building.govt.nz/building-code-compliance/d-access/accessible-buildings/about/practical-application-of-universal-design/

Morrison, R. L., & Macky, K. A. (2017, April). The Demands and Resources Arising from Shared Office Spaces. Applied Ergonomics, 60(April, 2017), 103-115. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2016.11.007

Mueller, B. J., Liebl, A., & Martin, N. (2020). Is wearing active-noise-cancelling headphones in open space offices beneficial for cognitive performance and employee satisfaction? INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings. 261, pp. 3002-3013. Seoul, Korea: Institute of Noise Control Engineering.

New Zealand Government. (2016, February 15). Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Government.

Nguyen, N. N., Varsani, K. V., Avgoulas, M. I., Carey, C., Drakopoulos, T., & Carey, L. (2024). The Effects of ‘Hot-desking’ on Staff Morale: An Exploratory Literature Scoping Review. Retrieved from: https://opal.latrobe.edu.au/articles/report/The_Effects_of_Hot-desking_on_Staff_Morale_An_Exploratory_Literature_Scoping_Review/26877511/2/files/48895486.pdf

Occupational Safety and Health Service. (1995). Guidelines for the Provision of Facilities and General Safety and Health in Commercial and Industrial Premises. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Labour.

Othman, M. K., Rais, S. L., & Azir, K. M. (2020). Exploring Determinants of Healthy Workplace Elements in The Office Building. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 498(1), 012084.

Pan, J., Chen, S., & Bardhan, R. (2024). “Reinventing hybrid office design through a people-centric adaptive approach”. Building and Environment, 252, 111219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.111219 .

Plimmer, G., & Cleave, E. (2017). Modern Office Design: Friend or Foe - Reviewing the Research. Wellington, NZ: Centre for Labour, Employment, and Work.

Rasid, M. F. A., Aris, M. A. M., Hamdi, N. H. Q. N. & Ramli, S. (2024). Examining Factors Influencing Employee Job Satisfaction in a Hybrid Work Setting: A Case Study of an Oil & Gas Company. e-Academia Journal of UiTM Cawangan Terengganu 13(1) 61-75

Richardson, A., Potter, J., Paterson, M., Harding, T., Tyler-Merrick, G., Kirk, R., & ...McChesney, J. (2017, December). Office Design and Health: A Systematic Review. New Zealand Medical Journal, 130(1467).

Roskams, M., & Haynes, B. (2021a). Environmental Demands and Resources: A Framework for Understanding the Physical Environment for Work. Facilities, 39(9-10), 652-666.

Samani, S. A. (2015). The Impact of Personal Control Over Office Workspace on Environmental Satisfaction and Performance. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 1(3), 163-172.

Sander, L. (2017, April 12). The Research on Hot-desking and Activity-based Work isn't so Positive. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/the-research-on-hot-desking-and-activity-based-working-isnt-so-positive-75612

Satumane, A. D. (2024) Influence of Environmental Design Factors on Perception and Performance of Indoor Occupants [PhD (Architecture) Thesis]. University of Oregon.

Scrima, F., Mura, A. L., Nonnis, M., & Fornara, F. (2021). The relation between workplace attachment style, design satisfaction, privacy and exhaustion in office employees: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 78, 101693.

Stacy, J. (2019, January 15). Psychological Impact of Hot Desking. Open Sourced Workplace. Retrieved from https://www.opensourcedworkplace.com/news/psychological-impact-of-hot-desking

Stohler, J. (2018, May). Flex-able Personalities: How Personality Moderates the Relationship Between Office Design and Employee Outcomes [Master’s Thesis]. Ithaca, NY, US: Cornell University.

Tokumura, T., Akiyama, Y., Takahashi, H., Kuwayama, K., Wada, K., Kuroki, T., ... & Tanabe, S. I. (2023). Impacts of implementing activity‐based working on environmental satisfaction and workplace productivity during renovation of research facilities. Japan Architectural Review, 6(1), e12345.

van der Voordt, T., & Jensen, P. A. (2023). The Impact of Healthy Workplaces on Employee Satisfaction, Productivity, and Costs. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 25(1). doi:10.1108/JCRE-03-2021-0012

van Duijnhoven, J., Aarts, M. P., Aries, M. B., Rosemann, A. L., & Kort, H. S. (2019). Systematic Review on the Interaction Between Office Light Conditions and Occupational Health: Elucidating Gaps and Methodological Issues. Indoor and Built Environment, 28(2), 152-174.

Veitch, J. A. (2011). Workplace Design Contributions to Mental Health and Well-being. Healthcare Papers, 11(Special Issue), 38-46.

Vischer, J. C. (2007). The effects of the physical environment on job performance: Towards a theoretical model of workspace stress. Stress and Health, 23(3), 175-184.

Vischer, J. C. (2008). Towards an Environmental Psychology of Workspace: How People are Affected by Environments for Work. Architectural Science Review, 51(2), 97-108.

Vischer, J. & Wifi, M. (2017). The Effect of Workplace Design on Quality of Life at Work. In Fleury-Bahi, G., Pol, E., & Navarro, O. (Eds). Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research (Chapter 20), pp. 387-400. London: Springer.

Williamson, S., Pearce, A., Dickinson, H., Weeratunga, V., & Bucknall, F. (2021). Future of Work Literature Review: Emerging Trends and Issues. Canberra, AUS: Public Service Research Group, UNSW.

Worek, M., Venegas, B. C., & Thury, S. (2019). Mind Your Space! Desk Sharing Working Environments and Employee Commitment in Austria. European Journal of Business Science and Technology, 5(1), 83-97. doi:10.11118/ejobsat.v5i1.159

WorkSafe. (2018, August). Workplace and Facilities Requirements. Wellington, New Zealand: WorkSafe New Zealand.

WorkSafe. (2018, September 17). Noise: What's the problem? Retrieved from: https://www.worksafe.govt.nz/topic-and-industry/noise/noise-whats-the-problem/

WorkSafe. (2019, February). Interpretive Guidelines: General Risk and Workplace Management. Wellington, New Zealand: WorkSafe New Zealand.

WorkSafe. (2019, July). Managing Thermal Comfort at Work. Wellington, New Zealand: WorkSafe New Zealand.

WorkSafe. (2019, August 20). What is Work-related Health? Retrieved from: https://www.worksafe.govt.nz/topic-and-industry/work-related-health/about-wrh/

WorkSafe (2018, p.1).

Vischer & Wifi (2017, p.5).

Vischer (2007, p.179).

Rasid et al. (2024, p.64).

Laughton & Thatcher (in Langer, 2021, p.31).

Ma, Ma, Li, & Kim (2021, p. 7).

WorkSafe (2018).

Langer (2021, p. 69).

Satumane (2024, p.44).

Pan et al (2024, p.12).

Bodin Danielsson & Theorell, (2024, p.3).

Satumane (2024, p.134).

Bergefurt et al (2022, p. 8).

Veitch, (2011, p. 42).

Roskams & Haynes, (2021, p. 388).

Satumane (2024, p.40).

Langer (2021, p. 43).

Satumane (2024, p.29).

Langer (2021, p. 67).

Mateescu et al., (2024, p.10).

Ahlberg and Blomberg (2024, p.32).

Roskams and Haynes (2021, p. 395).

Stohler (2018, p. 79).