Spotlight on: Mentally Healthy Work

A deep-dive into the importance of mentally healthy work, psychosocial risks, and approaches to support and strengthen mentally healthy work

Contents

Introduction

In the past five years, research undertaken in Aotearoa has consistently demonstrated a high incidence of decreasing mental health in our workplaces, including higher levels of stress, worsening experience of job demands, and poorer physical and psychological well-being.

In addition, globally, the evidence suggests poor mental health is creating an increasingly high burden, with one billion of the global population living with some form of mental disorder.

In this context, researchers have identified the workplace as an important contributor to our mental health and well-being, with the potential to have either a protective or negative influence.

The concept of mentally healthy work is an increasingly important one for businesses, organisations, and workplaces across Aotearoa to support all workers and helping them thrive in their various places of employment.

Key Principles

What is mental health?

To understand mentally healthy work, it's important to have a clear understanding of mental health. In Aotearoa, historically, mental health has been equated with mental illness; to put it another way, we often regard 'good' mental health as the absence of a mental illness (such as depression). In reality, however, as the WHO identifies, mental health is more complex.

"Mental health is a state of mental wellbeing that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community...it is crucial to personal, community, and socio-economic development...[and] is more than the absence of mental disorders. It exists on a complex continuum, which is experienced differently from one person to the next [sic]"1

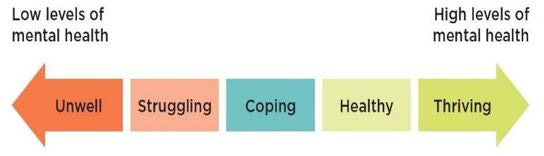

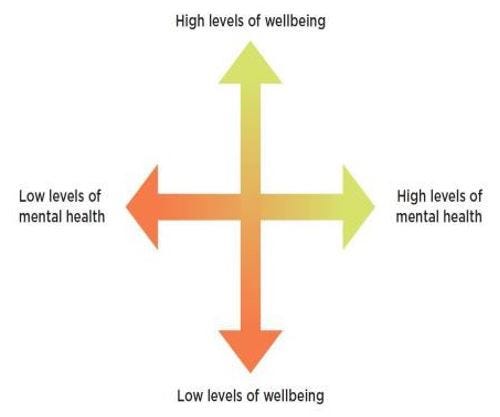

As noted above mental health is typically viewed as a continuum bounded by mental illness (or being "unwell") at one end and 'thriving' or 'flourishing' at the other.

An alternative perspective to this model is a dual continuum model. More akin to holistic models adopted by Māori and other indigenous communities, this model examines both the internal (horizontal axis) and external (vertical axis) factors that contribute to our sense of well-being.

This approach acknowledges that mental health and well-being is not something that exists in isolation; it is a feeling that is dynamically affected by our environment and interactions with others.

Regardless of the model used, the notion of mental health and well-being existing as a continuum means that, in all likelihood, the larger the organisation, business, or group, the greater the diversity of experience of mental health lived by the individuals within it and, importantly, this breadth will be continually changing and shifting.

Key to our understanding of mental health in the context of work (and, by extension, mentally healthy work) are two elements of the definition provided by the WHO.

The first - alluded to in the models above - is that an individual's mental health needs to be viewed as a 'complete package' whereby their overall mental health and well-being is influenced by work and vice versa, along with consideration of wider societal trends or "a largely physically safer but psychologically more challenging world".2

Second is the idea that an individual's mental health and well-being extends far beyond the absence of mental illness to a state of thriving or flourishing.

This wider consideration of mental health has implications for our understanding, development, and maintenance of mentally healthy work.

What is mentally healthy work?

Using the 2020 Position Statement provided by WorkSafe as a starting point, the Government Health and Safety Lead provides this definition:

"Mentally healthy work is work where the risks to workers' mental health are eliminated or minimised, and their wellbeing is prioritised ... [and] it does not cause psychological harm and may improve overall wellbeing [sic]"3

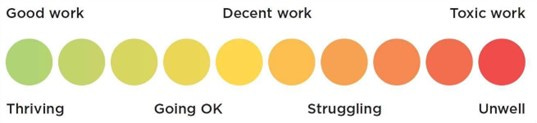

Conversely, of course, this means that work which may be psychologically harmful to a worker, or which may negatively affect or reduce their well-being, is not mentally healthy; this is referred to as 'toxic' work.

As with mental health, the difference between mentally healthy (or 'good') and toxic work can be illustrated on a continuum.

On the face of it, the definition above seems simple. But, in reality, there are a number of factors that work together to ensure people have work that allows them to flourish.

Before we explore the complex factors or risks linked to mental health at work, it's worth considering why mentally healthy work is so important.

Why is mentally healthy work important?

It goes without saying that protecting and promoting the mental health of all employees is important; this is because providing mentally healthy work has benefits for individuals, teams or business groups, the business/organisation as a whole, and - importantly - employees' lives outside work.

As noted in the introduction, the incidence of poor mental health at work is on the rise in Aotearoa. Research from 2019 found that, in the two years leading up to publication of its results, staff-reported stress had risen by 23.5%, while rates of absenteeism - resulting from stress - rose from 6.4 to 22.2% between 2016-2018 respectively.4 In addition, data from the Ministry of Health suggests that "20% of workers in any organisation at any one time, will be affected by a mental health challenge".5

More recently, a 2022 survey of more than 1,000 workers across Aotearoa found that 53% reported feeling burnt out in the three months leading up to the survey.6

Benefits of providing mentally healthy work

Workplaces support their employees by providing mentally healthy work, as this reduces the risk of injury and illness (physical and mental), while also increasing workers' well-being, helping them thrive and flourish. In turn, this increases productivity and performance, while reducing staff turnover, absenteeism, and presenteeism. This has down-stream effects for teams/groups as well as the wider organisation, helping meet its objectives and having a positive effect on the bottom line.

Providing mentally healthy work ensures employees "experience higher job satisfaction and morale, better physical and mental health, greater motivation, and the ability to manage stress more effectively."7 Recently, interviews with 57 workers from Aotearoa highlighted that for "most participants the psychosocial factors of work were...perceived as potentially more harmful than physical health and safety risks."8

The cost of poor mental health at work

The cost of poor mental health at work has been shown to be significant.

The Australian Government's Productivity Commission, poor mental health costs the economy "from $12.2 to 22.5 billion each year".9 In the US, meanwhile, approximately "one hour a week is lost as a result of depression-related absenteeism, while up to four hours a week are lost to depression- related presenteeism."10 Locally, research from 2020 showed poor mental health cost the economy in Aotearoa "7.3 million working days and $1.85 billion due to work absence".11 Research undertaken by WorkSafe in 2019 found that mental harm accounts for approximately 17% "of annual work-related disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost".12

Conversely, investing in workers mental health has demonstrable benefits for workers. In the UK in 2015, for example, research suggested that companies saw a return of £10 for every £1 spent on initiatives to support workers' well-being. More recent research indicates that, in Aotearoa, "for every dollar we invest in the wellbeing of our workforce...there is a $12 return".13

Poor mental health at work can result in mental harm which WorkSafe defines as taking place "when a significant cognitive, emotional, or behavioural impact arises from, or is exacerbated by, work-related risk factors...[this] harm may result from a single or repeated exposure [and] may be immediate (i.e., acute) or gradual (i.e., chronic)."14

“extensive research evidence shows that workers exposed to psychosocial hazards are at a greater risk of a range of poorer wellbeing outcomes related to both physical and psychological health, including, for example, stress, exhaustion and burnout, anxiety and depression, musculoskeletal disorders, and cardiovascular disease”15

In addition to effects at work, the provision or absence of mentally healthy work can affect life outside of work. Those experiencing poor mental health at work are exposed to negative effects such as increased reliance on substances (e.g., alcohol) to cope with stress, withdrawing from relationships, decreased motivation, difficulty sleeping, and worse relationships with partners, children/tamariki, and wider whānau members.

Importantly, as WorkSafe's John Fitzgerald notes: "exposure to psychosocial risks that can result in mental harm can happen to any worker, working in any industry, anywhere in New Zealand", making the need for mentally healthy work that eliminates or mitigates such risks more important.16

As noted above, exposure to mental harm can have implications for businesses and organisations too. Where psychosocial risks are identified in a business, there is more likely to be:

poorer engagement from workers

lower productivity

higher levels of absenteeism, presenteeism, and staff turnover; and

lower levels of job satisfaction and commitment among workers.

A requirement to provide mentally healthy work

Internationally, managing the psychosocial risks associated with poor mental health is enshrined in various work-based health and safety frameworks, regulations, and legislation. Although this point appears to escape the notice of many businesses, Aotearoa is no exception; the need to ensure the mental health of workers is captured by the Health and Safety at Work Act (2015).

“every time one reads the word 'health' in the Act, it is necessary to also consider 'mental health'. This includes, for example, the main purpose of the Act (section 3) which can be read as providing a balanced framework to secure the (mental) health and safety of workers and workplaces. Ensuring mental health and mentally healthy work are not new obligations, they are not an addendum… nor an additional responsibility for business owners, managers, and workers. It has always been there, hiding in plain sight."17

There is, then, a legal imperative for businesses to provide mentally healthy work that protects all workers from risks to their mental health, identifying, eliminating, and managing psychosocial risks. Importantly, this extends to "understanding the needs of workers, and what contributes to and diminishes their wellbeing, as well as actively managing risks to workers, work, and the work environment."18

In addition to legislation, the New Zealand Government, as an adherent to the 2015 Recommendation on Integrated Mental Health Skills and Work Policy, has additional obligations enshrined by the OECD. In terms of mentally healthy work, Part Ill of this document highlights several key elements, including responsive management, promotion, return-to-work strategies, and policy development.

What risks are linked to mentally healthy work?

We have seen that mental health at work - and, by extension, mentally healthy work - is a complex construct to which a number of risk factors are linked and, as noted above, anyone working in Aotearoa in any industry may be exposed to one or more of these risks at any time.

Risks to workers' mental health are known as psychosocial risks; there is a wide range of such risks and these may change depending on the industry, task(s) being undertaken, and workers' characteristics. The degree to which a worker is exposed and how they will respond to that exposure is influenced by a range of factors (for example, a worker's age, sex, ethnicity, experiences, or the state of their mental health).

In the recent standard - ISO 45003:202 7 - Occupational health and safety management - Psychological health and safety at work- Guidelines for managing psychosocial risks ("ISO 45003") - a psychosocial risk is defined as "the 'combination of the likelihood of exposure to work-related hazard(s) of a psychosocial nature and the severity of the injury and the ill- health that can be caused by these hazards”.19

Psychosocial risks "are workplace interactions or conditions of work that can negatively affect the health and wellbeing of workers [sic]".20 As such, they reflect the interactions between workers and the environment in which they work, as well as the complex interactions between employees as individuals, every aspect of their work, and workers' lives outside of the workplace.

In other words, the complexity of mental harm arising from exposure to psychosocial risks reflects that of mental health itself, with such harm involving "a complex interaction between workplace factors, work design, risk/exposure, and personal/individual factors."21

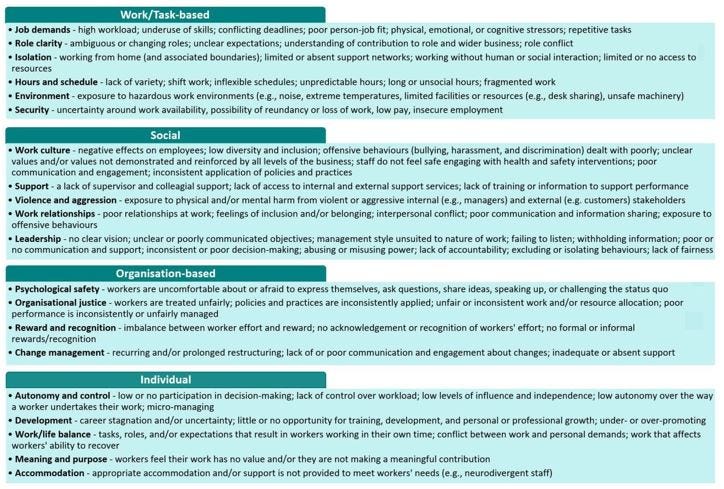

Psychosocial risk categories

Psychosocial hazards and risks can be categorised in several different ways. Earlier classifications divided psychosocial hazards into two groups ('work content' and 'work context'), while the Government Health and Safety Lead divided them into four categories:

task/work hazards

hazards associated with individuals

social hazards; and

organisational hazards

The ISO, meanwhile, identifies three main categories of psychosocial risk:

organisation factors

social factors; and

environment, equipment, and hazardous task factors.

This aligns with a definition of psychosocial factors of work, which identifies that these factors "refer to aspects of the design and management of work, and its social and organisational contexts, that have the potential to affect employee psychological or physical health".22

However, this categorisation, has been criticised for not considering the individual effects (e.g., capacity, expectations, level of fatigue etc.) that come into play.

Using data from multiple sources, the figure below identifies key psychosocial hazards and risks.

Where does stress fit in?

Aside from offensive behaviours (for example, bullying or discrimination), a commonly identified psychosocial risk is stress. According to WorkSafe "stress arises where work demands exceed the person's capacity and capability to cope".23

Research has identified a distinction between positive stress - sometimes called 'eustress' - and what we tend to think of in discussions of the phenomenon, the more negative 'distress'.

Eustress presents a number of benefits for workers, including challenging or mentally stretching them, acting as a motivator in the workplace and supporting people's ability to solve problems, and building their resiliency. In addition, eustress can bring people together, strengthening social connections. For such situations to have benefit, however, businesses, organisations, and managers need to ensure appropriate resources and supports are in place; without it, eustress can become distress, resulting in mental harm to workers.

Negative stress can lead to many forms of mental harm, including depression or burnout, and can also manifest as physical harm, contributing to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular or respiratory disease, diabetes, and cancer. This is especially concerning when we consider that such NCDs "are the leading causes of premature deaths and preventable ethnic and socioeconomic health inequalities in Aotearoa"24

Consequently, although beneficial in some contexts, stress - which falls into many of the sub-categories of psychosocial risk listed above - can be a serious risk to workers' mental health.

Addressing stress requires a similar approach to that used to combat other psychosocial hazards; crucially, it is not enough to address the effects of stress, it is important to "look at organisational factors that may be contributing to stress...and look to manage them in a systematic way."25

Identifying hazards and risks

Under the Health and Safety at Work Act (2015), identifying psychosocial hazards and risks is an essential step required of all employers in Aotearoa.

"Many causes of workplace stress and harm...are simply not even recognised by employers, so they are not identified as hazards. If they are not recognised, there is no hope of implementing an action plan to eliminate them."26

As part of its legislative obligations, a business or organisation should already have one or more mechanism in place for all staff to identify and/or report hazards and risks; this includes those related to workers' mental health. However, the complexity of mental health and variability of its effects means that a more structured approach might be necessary.

There are a range of tools and approaches businesses can use, including interviews, focus groups, surveys, observations, or workshops. One such tool is the Mental Wellbeing by Design resource developed by the Business Leaders' Health and Safety Forum; this provides a mechanism for teams to - in a workshop forum - explore risks at the task, individual, social, and organisational levels.

By adopting robust processes and systems for identifying psychosocial hazards and risks, workplaces can ensure they are developing and implementing the most appropriate interventions to help workers thrive.

Foundations

Supporting models of mentally healthy work

Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Mentally healthy work is reflected in the Hierarchy of Needs model developed by Maslow in the 1940s. This model posits the opinion that human behaviour is driven by a compulsion to meet five particular types of need.

With this model, when the four lower 'basic' and psychological needs are not met, individuals can be harmed; when these needs are met, an individual can flourish.

From a workplace health and well-being perspective "keeping workers physically safe is not enough, businesses also have an obligation to keep them psychologically safe - actually to support them to thrive… this means also supporting [workers'] collegial and social engagement, treating them with respect, supporting their productivity and recognising their contributions etc."27

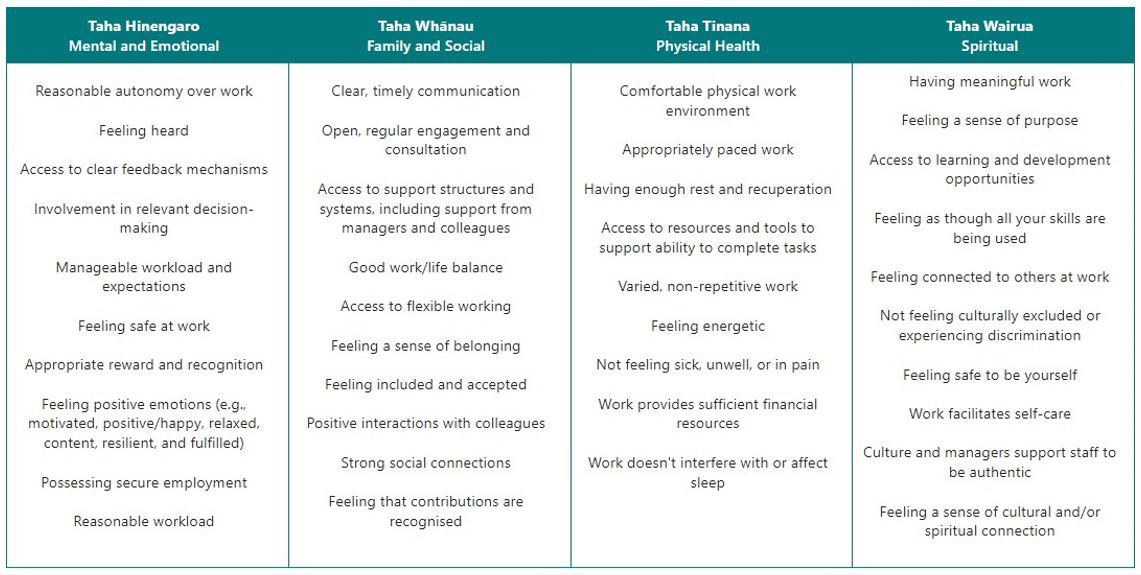

Te Whare Tapa Whā

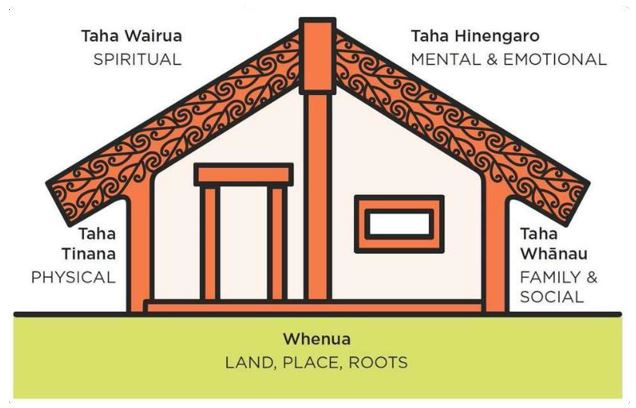

Earlier, we discussed the complexity of mental health and the need to consider this concept from an holistic perspective that weighs up multiple interacting factors. This approach is reflected in Mason Durie's Te Whare Tapa Whā model that, in Aotearoa, is a commonly used method for conceptualising health and well-being.

This model considers hauora (health) as being comprised of four walls of a whare (house), with each wall representing a separate domain of health:

Taha Wairua/spiritual well-being

Taha Hinengaro/mental and emotional well-being

Taha Tinana/physical well-being

Taha Whanau/family and social well-being

These four domains of Te Whare Tapa Whā work in concert to ensure our hauora is balanced; when one or more of these elements are out of balance, our well-being is affected.

The table below illustrates how mentally healthy work overlaps with each of these domains.

Providing mentally healthy work

As we've explored above, the risks to workers' mental health are many and varied; consequently, interventions and practices to support workers' mental health (that is, provide mentally healthy work) need to be multi-faceted to address the full range of risks, address the burden of mental health on workers, and support them to thrive and flourish.

"The opportunity for all organisations, regardless of size, is to design mentally healthy work that enables people to thrive. A person thrives when they feel, and function, well across multiple domains of their life. When a person thrives, they are confident and have positive self-esteem, build and maintain good relationships, feel engaged with the world around them, live and work productively, cope with the ups and downs of daily life, and adapt and manage in times of change or uncertainty."28

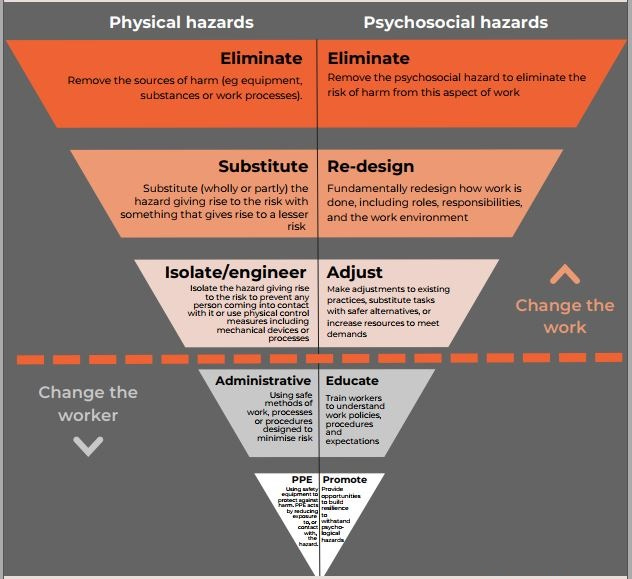

Multi-level interventions and a wider ecology

Across all health and safety practice, businesses and organisations across Aotearoa are encouraged to work within a hierarchy of intervention levels, with elimination as the 'gold standard' intervention. Addressing mental health at work is no exception.

Historically, businesses and organisations work at the the lowest level of this hierarchy, providing support for individuals such as access to EAP or similar counselling services, return-to-work plans, or referrals to other external services.

Instead, however, workplaces need to focus on multi-level approaches, with a particular emphasis on the top, primary level of interventions (that is, those that seek to redesign work and, in doing so, eliminate psychosocial hazards and risks).

Alongside the need to focus on elimination is that of ensuring the wider context for workers is considered. As noted in the literature, "it is important to recognise that workplaces sit within in an ecological system where they exist in relationship with all other parts of that ecological system...[and] that the social, physical, and cultural aspects of this multi-layered environment each have a cumulative effect on health."29

While this complex, holistic approach makes it difficult to design effective interventions, ignoring this consideration carries additional risk. In particular, any intervention that ignores the wider contexts in which workers live (and work) ensures that any such approach will fail to ensure individuals can thrive.

What makes an intervention effective?

Before exploring different interventions, it's important to have some understanding of what, according to research, makes such approaches effective.

As noted above, responses have often focused on approaches that support individuals and findings from research exploring these tertiary-level interventions and/or workplace well-being initiatives are mixed. In terms of the former, those based on mindfulness have been shown to be most effective, although researchers warn of avoiding a surface-level, 'McMindfulness' approach.

Bennett suggests the efficacy of strategies that focus on individuals may depend on a range of factors, including (but not limited to) its appropriateness for the organisation's context, focus, impact, and consistency of application.

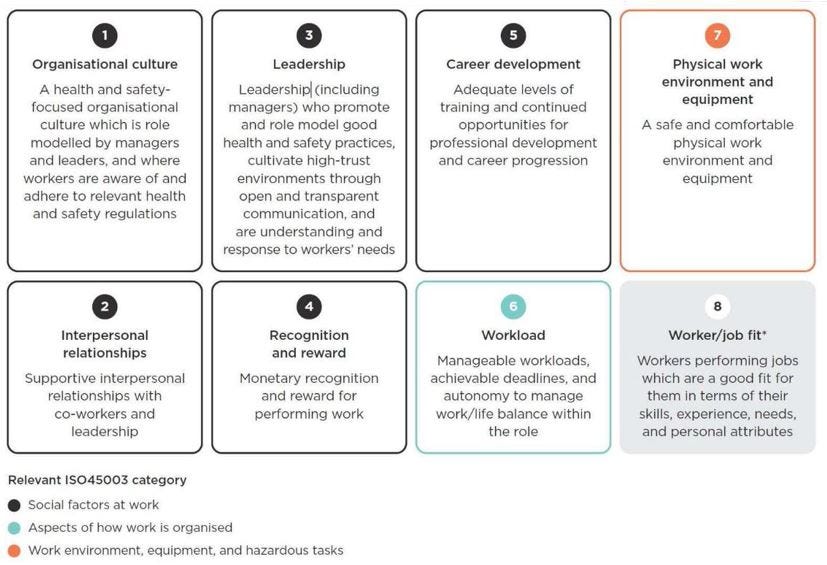

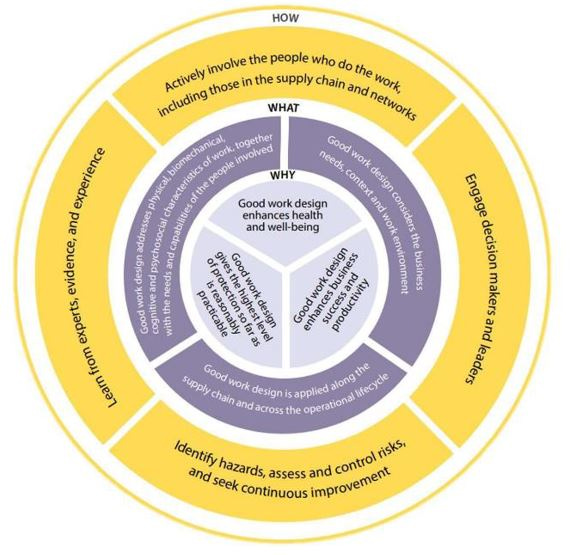

In its Principles of Good Work Design SafeWork Australia identified a set of 10 principles that are designed to show businesses how work and processes can be designed to support good work.

In 2021, Australia's National Mental Health Commission published a 'blueprint' resource on mentally healthy work. Its authors identified eight core principles for the process of establishing - and, by extension, measuring the efficacy of - mentally healthy work in a business.

Broadly speaking, these principles align with a key tenet put forth in ISO 45003 as a marker for effectiveness: "The success of psychosocial risk management depends on commitment from all levels and functions of the organisation, especially top management"30

Similarly, in 2022, WorkSafe released findings from a project examining what 'good work' that protects workers' well-being looks like in Aotearoa. Participants identified a set of protective factors that contribute to workplace well-being; arguably, these factors can be considered to be 'markers' of what makes interventions effective.

Interventions

Introduction

Keeping the general considerations discussed above in mind, there are several essential approaches for providing and supporting mentally healthy or 'good' work.

When designing such work, it is important businesses and their managers keep in mind the following:

"Effective design of good work considers:

The work:

how work is performed, including the physical, mental and emotional demands of the tasks and activities

the task duration, frequency, and complexity, and

the context and systems of work.

The physical working environment:

the plant, equipment, materials and substances used, and

the vehicles, buildings, structures that are workplaces.

The workers:

physical, emotional and mental capacities and needs [sic]"31

Re-designing work culture

An organisation's culture is a key psychosocial hazard and, while it is often categorised as a 'social' hazard, it is an element of work design that influences all domains of our health and well- being.

A positive workplace culture can serve as a protective factor for workers' mental health and well- being, while also influencing engagement practices, productivity, and staff turnover.

While workplace culture is a dynamic, 'live' construct that can change over time, its development comes from attempts to establish a specific focus within an organisation and is driven by the organisation's leaders.

To support mentally healthy work, business leaders need to work on developing a workplace culture that has elements and characteristics identified on the figure below.

Redesigning the culture of a workplace first involves working with employees to assess the current culture via multiple processes, such as surveys, focus groups, and interviews. From this process, leaders can work with staff and their representatives to map out the values, attitudes, and behaviours they wish to include in the re-designed culture.

It's important to keep in mind that this is not a quick process; leaders may need to start changing work practices while providing training and support for leaders - these steps will feed into re-shaping a more positive culture.

"approaches can [include]... building support networks; opening discussion among managers about how to foster healthy work behaviour; replacing stigma with positive affirmation; starting the conversation around mental health; and leading by example... [and also taking steps] to address work design: reducing psychological and physical demands of work; increasing employees' control over their work; creating a supportive and trusting environment; training leaders on building a positive organisational culture; designing and implementing relevant policies; providing support and resources; and encouraging communication."32

Diversity and inclusion

A workplace that promotes and supports diversity and inclusion is often called out as a key element of a positive workplace culture and, by extension, of mentally healthy work. A focus on diversity and inclusion "has a positive impact on staff engagement, productivity, growth, innovation, and the overall resilience and adaptability of an organisation", while also providing a mechanism for different approaches to problem-solving.33

To strengthen diversity and inclusion ("D&I") in the workplace, businesses can:

develop, implement, and maintain D&I policies and strategies

this should include a definition of the behaviours expected of staff that support D&I and mechanisms for measuring and evaluating D&I targets and goals

re-shape recruitment practices to actively promote and support D&I

ensure leaders have the knowledge, tools, and resources to promote and support D&I

provide training to staff on key concepts such as bias and neurodiversity

engage with staff on ways to improve practices and policies; and

use communication channels to promote and support D&I

Reward and recognition

Ensuring staff are rewarded and recognised for their mahi was a key protective factor identified by WorkSafe and lack - or inappropriate examples -of recognition and reward in the workplace is, in and of itself, a psychosocial hazard. Providing such recognition fulfils one of Maslow's 'esteem' needs and is essential for our health and well-being.

Reward and recognition also has a number of important interconnected benefits including, but not limited to, raising morale and job satisfaction, improving employees' sense of belonging, improving productivity, and reducing absenteeism and presenteeism.

While pay is an obvious - and vitally important - form of reward, research suggests that some would rather be paid less and, instead, receive or have access to working conditions that enhance well-being and that such non-monetary forms of recognition are more valued than monetary rewards.

There are several avenues open to businesses and leaders for rewarding and recognising their employees' efforts, including:

establishing and implementing a formal reward and recognition policy and programme

it is essential this is developed in concert with employees and is not a purely 'top down' approach

ensuring workers have opportunities to apply their skills and knowledge via diverse, interesting, and challenging work

giving staff opportunities for development

ensuring leaders have the skills, knowledge, and resources to support reward and recognition processes

it may be useful to include a requirement for demonstrating how managers have rewarded/recognised staff in performance management systems

using different mechanisms to praise and recognise efforts, including:

formal recognition (e.g., manager-led promotions or salary increases or long service awards)

informal recognition (e.g., activities led by managers or peers at the organisational or team level such as annual health and safety awards or office morning tea shouts).

everyday recognition (e.g., recognition in team or similar meetings, verbal or written thank-you messages, or E-cards or e-certificates).

Addressing stigma, bullying, and other offensive behaviours

The social stigma associated with mental illness and poor mental health is a particular burden both on the individual and society at large that can result in worse outcomes for those living with poor mental health. In addition, the conflation of 'mental illness' with 'mental health' often results in a range of poor outcomes for individuals and makes it more difficult for people to understand and empathise with others' experiences, resulting in further stigma and discrimination.

Despite the fact that nearly everyone experiences poor mental health at one time or another, workplaces are not immune to the proliferation of stigma and discrimination; such proliferation can prevent the development of a healthy, positive work culture.

Similarly, a culture in which stigma and discrimination is tolerated can give rise to an increase in workplace bullying, which - as well as having devastating effects for workers, witnesses, and the wider organisation - can significantly undermine efforts to promote mentally healthy work.

All employees have a right to personal respect and to not be subjected to discrimination, bullying, or harassment; by making a concerted effort to stamp out such behaviours, businesses can foster a positive culture and, in doing so, protect all workers.

In addition, under Part Ill of the OECD's Recommendation on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy, workplaces have a mandated responsibility to address stigma and discrimination in the workplace.

A key step in supporting a mentally healthy culture is for businesses to take a formal, consistent, transparent, and evidence-based approach to preventing and responding to bullying, harassment, and discrimination. Components of this approach can include:

having a robust Code of Conduct in place that sets-out behavioural expectations

implementing values and designing policies so they:

ensure recruitment practices do not discriminate against those living with (or having lived with) mental illness

keep people with experience of mental illness in the workforce

foster a supportive environment that ensures all workers feel valued and cared for, regardless of their characteristics or experience

fostering a psychologically safe workplace; and

using training and engagement to raise awareness and understanding of mental health and offensive behaviours.

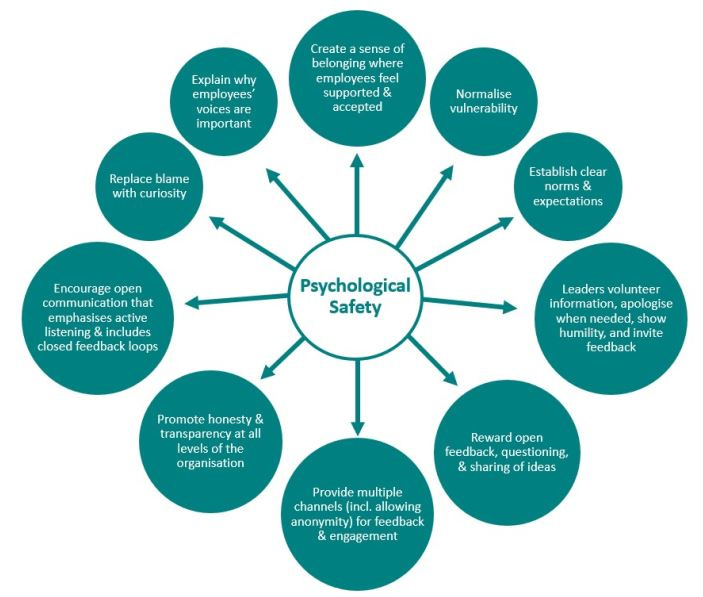

Foster psychological safety

Decades of research has pointed to psychological safety - the shared belief workers hold around whether it is safe to take risks, such as speaking up or admitting mistakes, without fear of punishment or humiliation - as a key enabler of mentally healthy work.

Psychological safety doesn’t just help people feel good at work, although it does that. It doesn’t just help foster a more diverse and inclusive work environment, although it does that as well…it substantially contributes to team effectiveness, learning, employee retention, and - most critically - better decisions and performance.34

Low psychological safety represents an organisational psychosocial risk that can result in harm for all workers. As well as helping mitigating the risk of this harm, fostering psychological safety in teams and businesses can:

improve productivity and performance, including safety performance

support teamwork

support learning and development

give workers a voice

boost creativity and innovation

improve inclusivity and workers’ sense of belonging

The level of psychological safety in an organisation can be influenced by a range of factors, including workers’ relationships, the length of time a group of employees work together, individuals’ actions (as acts of risk-taking can encourage others to take similar risks), the wider organisational culture, and the way work is designed.

One of the main determinants of psychological safety is leaders’ behaviours and style of leadership. Leaders can ‘make or break’ psychological safety by the degree to which they:

model psychological safety (e.g., admitting when they’ve made a mistake or don’t know something)

demonstrate support for and buy-in of mechanisms aimed at improving psychological safety

support team members’ risk taking behaviours (e.g., publicly and privately recognising and rewarding positive risk taking)

provide support for workers’ well-being

Employees’ perceptions of the degree to which their manager(s) demonstrate these behaviours influences the psychosocial safety climate (i.e., the belief that managers will protect and support workers’ psychological health and safety).

A poor psychosocial safety climate is talked about as the 'cause of causes' of work stress and is the leading psychosocial risk factor at work capable of causing psychological and social harm through its influence on other psychosocial factors.35

Recent research from Europe into the IT industry has examined which leadership styles are best suited to support psychological safety. According to Koutny and Chatziadam36, transformational, servant, and demoncratic leadership styles are more closely associated with high levels of psychological safety.

Alongside key leadership behaviours, the figure below illustrates approaches the relevant literature has identified as being important for fostering psychological safety.

Providing effective leadership

An essential element of providing mentally healthy work is for businesses to support and provide effective leadership.

Leaders - especially senior leaders - have "a strong influence over what a person experiences while they are at work, including whether the conditions they work in are harmful or supportive to their mental wellbeing [sic]"37

While managers cannot be held responsible for ensuring the mental health of employees outside of work, research suggests the support they provide is vital, particularly for managing spillover (i.e., the effect and impact work has on employees' personal lives).

Ensuring workers' maintain a high level of well-being at work via the provision of mentally healthy work, as well as possessing awareness and understanding of psychosocial risks, is a responsibility that comes from the top down through leaders and managers at every level of a business.

Alongside this responsibility is the support and buy-in leaders bring to interventions and strategies that support and foster mentally healthy work, without it, such approaches are doomed to failure.

Importantly, businesses need to provide their leaders with the resources, tools, and support they need to understand psychosocial hazards and risks, support mentally healthy work, and make the behavioural changes needed to support their team members.

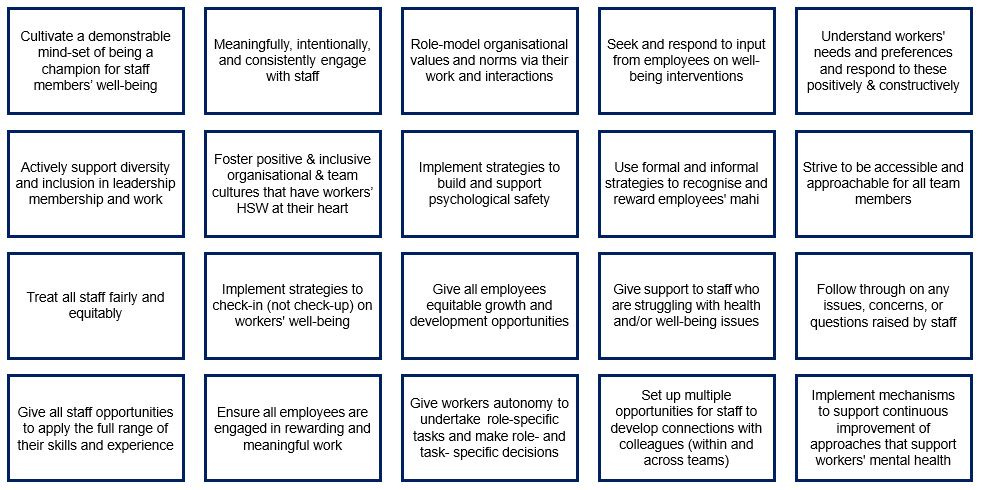

The figure below lists key behaviours and approaches leaders need to take to support workers' mental health and provide mentally healthy work.

Understanding employees

A key behaviour leaders can leverage is understanding the individuals that make up their teams.

Modern workplaces acknowledge that the whole person comes to work and our expectations of what this means are changing. This makes understanding what people intrinsically value central to how workplaces design their work and environment to support wellbeing. To do this not only benefits businesses but has wider impacts on whanau and communities - as wellbeing is relational and cannot be achieved alone [sic]38

Taking the time to understand your workers not only strengthens leaders' relationship with their team members but also provides opportunities to develop interventions that are tailored to employees' needs and preferences, while supporting their overall well-being. Importantly, engaging in korero to understand workers and their perspectives helps fulfil obligations under the Health and Safety at Work Act (2015).

There are, of course, a number of ways leaders can do this, including via one-on-one discussions, team workshops and team-building exercises, as well as more formal approaches, such as e-surveys. Regardless of the method used, the need for leaders to understand their team members and their needs and preferences is essential to creating and supporting mentally healthy work.

Effective engagement and communication

In the wider context of health and safety, it is well understood that effective engagement and participation is key to achieving success. This is no different for mental health and well-being at work.

A corporate mental health strategy is only as strong as the communication efforts behind it.39

To foster mentally healthym work in a sustainable way, organisational communication needs to:

include multi-directional engagement that takes place at all levels of an organisation; and

leverage a range of communication tools and strategies

While an open, collaborative approach to engagement needs to be led by organisational leaders, the level of trust in the manager-worker relationship is a key consideration. Consequently, the need to develop and sustain a positive workplace culture with a high level of psychological safety goes hand-in-hand with effective engagement and communication.

One way of strengthening trust within the business is to engage in whakawhanaungatanga - an on-going process of developing and bolstering relationships. Building these relationships will help develop trust, while affording opportunities for getting to know employees, and embarking on kōrero relating to mental health and well-being.

There are innumerable formal and informal options available to businesses for engaging in effective engagement across multiple platforms; many businesses employ communication specialists who should be available to support the development of an effective engagement strategy.

Regardless of the methods used, it is important to remember that, in terms of supporting their well-being, such a strategy can act as a protective factor for workers, making it an essential tool in providing mentally healthy work.

Raising awareness and understanding

A key control measure that can be used to mitigate the risk of mental harm is to provide education and training to raise awareness and understanding of mental health, psychosocial risks, mental illness, and mentally healthy work.

This can be achieved by:

sharing resources

using existing communication channels (e.g., workplace intranets)

providing access to mobile apps (e.g., Headspace)

running workshops; and/or

providing and/or accessing formal training to leaders and other key staff (e.g., Health and Safety Representatives).

However, it's important to be aware that, although well- intentioned, the efficacy of such initiatives is variable and may be influenced by a range of factors.

These types of interventions can have a number of positive benefits for individual employees, including improving healthy lifestyle habits (e.g., healthy nutrition and exercise choices), serving a protective role for mental health, and strengthening workers' resilience.

Combined with an environment in which there is a high level of psychological safety, awareness and education interventions can encourage staff to seek help earlier or prompt workers to provide support to their colleagues. Finally, providing training to, in particular, leaders/managers is especially important in supporting workers' well-being.

This mahi can be supported by establishing well-being or mental health 'champions'. Drawn from different levels within a business, these individuals can:

promote mentally healthy work

help raise awareness of mental health and associated topics

support interventions to reduce stigma; and

help support leaders, especially those struggling to understand the benefits of supporting mental health and well-being and/or having difficulty implementing one or more interventions.

Using champions with lived experience of mental illness may be particularly beneficial in this type of role.

Building and strengthening social connections

Having positive social connections at work has been described as "one of the most powerful factors" for supporting workers' mental health and well-being.40 Developing relationships with those we work with is, for many (but not all), a normal part of working and is seen as a hallmark of a healthy working environment.

Businesses characterised as a mentally healthy place to work actively support and enable its workers to build - not just professional but, also - social relationships.

Employees with a 'best friend' at work have been shown to be more productive, focused, and enthusiastic about their work, while also having fewer sick days; having these types of relationships also strengthens workers' sense of self and, in turn, supporting their well-being.

In a recent study, WorkSafe found that workers across Aotearoa understand the importance of workplace relationships, with some noting that “the people can make or break a workplace".41 These same research participants also underscored the value of social elements, identifying the ability and opportunity to have 'downtime' with co-workers and have a laugh as particularly positive factors.

In these ways, social relationships at work serve as a protective factor for workers mental health and well-being. Consequently, businesses need to support and facilitate social interaction and teamwork by, for example, providing comfortable facilities (such as staff lounge areas), organising team days or workshops, and supporting events in and out of work.

Additional supports

As well as the key elements discussed above, businesses can foster mentally healthy work by strengthening good work design, focusing on the physical environment, and providing access to tertiary-level services.

Strengthening good work design

Good work design is about taking a systems-level approach to supporting well-being, using a range of interventions across the hierarchy of controls. In addition to the elements of good work design already discussed, there are additional supports businesses can put in place.

Autonomy

As noted above, a lack of autonomy can be a psychosocial hazard for workers, acting as a negative influence on employee's mental health.

Repeatedly and actively withholding autonomy in an individual's role (for example, engaging in micro-managing or not acceding control over workflow) is an example of workplace bullying and, as such, can - particularly when combined with other negative behaviours - have a significant effect on an employee's mental health.

Conversely, research suggests an appropriate level of autonomy can have a positive effect on individuals' overall health and may also support workers' work-life balance.

High levels of psychological safety and robust mechanisms for reward and recognition are important for boosting workers' autonomy and, in addition, when considering the level of autonomy to give an individual employee, it is important leaders have a good understanding of the particular worker, as not everyone responds in the same way to high - or low - levels of autonomy.

The best approach, therefore, is to spend time understanding workers' needs and preferences, exploring what autonomy looks like for individuals (e.g., control over workload or flexible work) and collaborating with them to ensure expectations are met while meeting those needs.

Training and development

Similarly, equitable access to training and development opportunities is consistently identified as being either a positive (when it is provided) or negative (when it is withheld) influence on mental health and well-being. As well as supporting health and safety more generally, training and development opportunities can help employees feel valued and appreciated.

In contrast, withholding training and development opportunities from an individual employee can be viewed as an example of workplace bullying, undermining their health and well-being.

This intervention can act as both a primary- (e.g., organisation-wide training) and tertiary-level (e.g., resilience training for individual workers) control measure; while the former is more effective in fostering mentally healthy work, the latter has a place in supporting individuals when they are exposed to mental harm.

As we've seen, training and development has an important role in reducing stigma, fostering development of a positive culture, and supporting leaders to be effective.

Leaders need to spend time working with their employees to identify training needs and construct individual development plans. At the organisational level, senior leaders need to leverage engagement opportunities to identify development needs that will support the well-being of all staff, while working with specialists and subject-matter experts to understand which topics should be included as 'core' training for staff.

Flexible work

The provision of flexible work is also seen as a constructive step businesses can take to support their employees' well-being. Alongside other forms of autonomy, offering flexible hours and/or a flexible location can support workers' work-life balance, improve job satisfaction, increase trust, and act as a way of preventing bullying.

By developing a formalised policy and/or position and engaging workers to understand their needs and preferences, workplaces can further support mentally healthy work via flexible working.

Individual accommodations

Businesses can support workers' well-being by providing accommodations - changes to the physical environment or work design/approach that support workers living with a disability. Providing these changes is mandated under the Human Rights Act (1993).

In terms of mental health, accommodations may include changes such as flexible work, providing additional supervision, allocating 'light duties' in times of need, or allowances for mental health leave.

As with the supports listed above, successfully providing accommodations for staff requires engagement with employees to understand their needs, doing so will strengthen relationships between leaders and their team members, while ensuring any support plan that is developed is done so as part of a collaborative relationship.

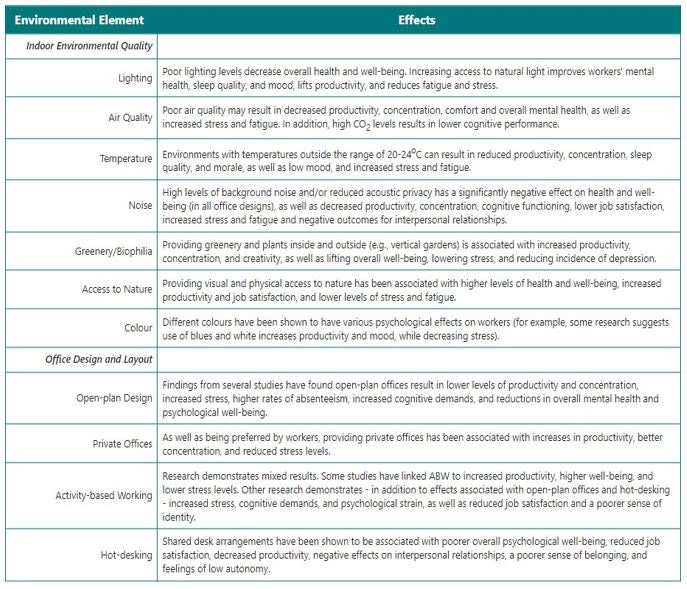

Improving the physical environment

Workplace physical environments are another key element that can support - or hinder - workers' mental health and well-being. Identified as a psychosocial hazard in several frameworks, considering the physical environment alongside psychological aspects of workers' well-being fits with holistic or ecological models.

Importantly, the ISO 45003 makes a distinction between the environment, equipment used at work, and hazardous tasks undertaken in those environments.

The physical environment at work has been defined as including "not only the objective physical stimuli within the workplace but also the ways in which these stimuli are subjectively perceived by the individual occupants"42

Researchers have identified a number of elements of physical environments that can influence workers' health and well-being as well as, in some instances, the wider business.

To support workers' well-being, businesses need to carefully consider each of these elements, ensuring workers' health is put ahead of cost-savings or similar concerns when undertaking workplace design and refurbishment ensuring - at the very least - workplaces are "clean, healthy, safe, accessible and well maintained so work can be carried out without risks to worker health and safety."43

Support services

Businesses in Aotearoa have been criticised for their over-reliance on tertiary-level interventions that are triggered in response to individual workers' complaints of mental harm. However, services such as Employee Assistance Programmes (EAP), supervision, and mental health first aiders have an important complementary role as part of an integrated approach to mentally healthy work.

Businesses need to ensure they have these mechanisms in place, as such services are important in:

providing clinical support

helping workers cope with the stress of, for example, offensive behaviours

assisting with return-to-work plans; and

raising awareness of psychosocial risks and mental illness.

Further resources and support

Resources

There are a number of resources available for those looking to learn more about mentally healthy work, some of these are listed below.

Mentally Healthy Work Hub – Government Health and Safety Lead

Mental Health – WorkSafe

Workplace Well-being – Mental Health Foundation

Working Well resources – Mental Health Foundation

Mental Health at Work – World Health Organisation

Mental Health at Work – MBIE

If you have a concern regarding mentally healthy work at your workplace or organisation, you should take the following steps:

If you feel comfortable doing so, raise the issue with your Manager or Leader.

Talk with your local Health and Safety Representative or, if applicable, union representative.

Depending on the seriousness of the issue, other organisations, such as the Police, the ERA, Citizens Advice, or the Human Rights Commission, may be more appropriate - the WorkSafe resource shown here provides guidance on who to speak to when.

You can also raise the concern with WorkSafe, but there are specific parameters around when WorkSafe will investigate and/or intervene.

Help and Support

If you are experiencing difficulties, there are services you can access for support:

Depression Help – 0800 111 757

Free call or text 1737

Healthline – 0800 611 116

Lifeline Aotearoa – Text 4357

Samaritans – 0800 726 666

Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 TAUTOKO (828 865)

What’s up – 0800 942 8787

Youthline – 0800 376 633

Bibliography

Asaari, M., Desa, N., & Subramaniam, L. (2019). "Influence of salary, promotion, and recognition toward work motivation among government trade agency employees". International Journal of Business and Management 74(4), 48-59.

Association of Consulting and Engineering (September 23, 2021). Mental Health isn't about Preventing Sickness - it's about Flourishing.

Beck, G. (2022). "Systems of thinking, systems of work." In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.251-266. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Bennett, H. (2022). "Mentally healthy work: Obligations and opportunities". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.83-98. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Bergefurt, A. G. M., Weijs-Perree, M., Appel-Meulenbroek, R., & Arentze, T. A. (2022). "The physical office workplace as a resource for mental health - A systematic scoping review". Building and Environment, 207A, [108505].

Best, T., Visser, R., and Conradson, D. (2021). "Stress, psychological factors and the New Zealand forest industry workforce: Seeing past the risk of harm to the potential for individual and organisational wellbeing". New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 57(5).

Beyond Blue (2022). Work and Mental Health.

Blackwood, K., D'Souza, N., Port, z., and Tappin, D. (2022). "Psychosocial factors: Pathways to harm and wellbeing". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.112-130. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Bone, K., and Gardner, D. (2022). "Organisational culture for psychological health at work". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.143-157. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Business Leaders' Health and Safety Forum (April, 2021). Protecting Mental Wellbeing at Work: A Guide for CEOs and their Organisations. Business Leaders' Health and Safety Forum: Wellington, NZ.

Catley, B. (2022). "Workplace bullying in New Zealand: A review of the research". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.172-217. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Cooper, V. (2022a). "How we korero about mental wellbeing matters". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.99-111. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Cooper, V. (2022b). "Stress - Has it had a bad reputation?" In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.218-231. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Corey, D. (August 21, 2018). How to Build an Employee Recognition Pyramid with Peer-to-Peer Recognition.

Donald, J., Johnson, A., and Nguyen, H. (2019). Workplace well-being: A critical review and the case of mindfulness-based programs. In R. Lansbury, A. Johnson, and D. van den Broek (Eds.) Contemporary Issues in Work and Organisations, pp.224-236. Routledge: London, UK.

Dyhrberg, S. (2022). "The Health and Safety at Work Act and psychosocial risks: Change the legislation or change our mindset?". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.73-82. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Employers and Manufacturers' Association (August 7, 2022). Workplace Wellbeing.

Employment Hero (2022). Wellness at Work.

Faulkner, L., Molloy, C., and Handley, K. (May, 2021). When Size Matters: Creating Mentally Healthy Workplaces. University of Newcastle: Callaghan, NSW.

Fitzgerald, J. (2022). "Mentally healthy work: The drive to thrive". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.56-72. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Gallo, A. (February 15, 2023). What is Psychological Safety?

Government Health and Safety Lead (May, 2021). Creating Mentally Healthy Work and Workplaces: A Guide for Public Sector Health and Safety Leaders and Practitioners. Government Health & Safety Lead: Wellington, NZ.

Government Health and Safety Lead (June 21, 2022). Mentally Healthy Work 101.

Hammoudi Halat, D., Soltani, A., Dalli, R., Alsarraj, L., and Malki, A. (2023). "Understanding and fostering mental health and well-being among university faculty: A narrative review". J. Clin. Med. 2, 4425.

Hopper, E. (February 24, 2020). Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Explained.

Koutny, N. & Chatziadam, P. (2023). Creating a Safe Workplace: Leadership and Psychological Safety [Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science]. Stockholm University: Stockholm, Sweden.

MacKenzie, P. (2022). "Positive and negative spillover: An intersection of work and personal life". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.232-250. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Mental Health America (2022). Why is Employee Recognition Important?

Mental Health Foundation (2016). Working Well: A Workplace Guide to Mental Health. Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand: Auckland, NZ.

Mental Health Foundation (2023). Statistics on Mental Health and Wei/being in New Zealand Workplaces.

National Mental Health Commission (2021). Blueprint for Mentally Healthy Workplaces. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care: Sydney, NSW.

Olakoyenikan, S. (December 7, 2020). 75 Ways to Promote Psychological Safety at Work.

Riegan, J. and Norriss, H. (2022). "Mentally healthy work in Aotearoa New Zealand". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.14-37. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Safe Work Australia (2020). Principles of Good Work Design. Safe Work Australia: Canberra, ACT.

Sander, E. J., Caza, A., & Jordan, P. J. (2019). "The physical work environment and its relationship to stress". In 0. Ayoko, & N. Ashkanasy (Eds.), Organizational Behaviour and the Physical Environment (pp. 268-284). Routledge.

Saunderson, R. (2004). "Survey findings of the effectiveness of employee recognition in the public sector". Public Personnel Management, 33(3), 255-275.

Saunderson, R. (November 3, 2021). Where Should I Focus My Time on Improving Recognition at Work.

Seitenbach, J. (2019). An Exploratory Study of How Millennials Approach and Communicate Mental Health in the Workplace [Thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements of a Master of Arts]. City University of New York: New York.

Sushil, Z., and Watts, K. (2022). "Growing a wellbeing movement at work". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.267-281. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Thompson, M. (2022). "Mentally healthy work in the public service". In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.282-296. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Walker, M. (2022). The Effects of Office Design on Workers' Health, Safety, and Well-being: Findings and Lessons from Research. [Unpublished literature review]

Walker, M. (May 29, 2023). Spotlight on Workplace Bullying.

Walker, M. (2024a). Mentally Healthy Work: An Introduction. [Unpublished e-book]

Walker, M. (2024b). Spotlight on Psychological Safety.

WorkSafe. (August, 2018). Workplace and Facilities Requirements. Wellington, New Zealand: WorkSafe New Zealand.

WorkSafe (August 19, 2020). Work-related Health Estimates and Burden of Harm.

WorkSafe (June, 2022). New Zealand Psychosocial Survey 2021. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

WorkSafe (August, 2022). Work-related Wellbeing: What Good Looks Like - New Zealand Workers' Perceptions of the Wei/being-enhancing Factors of Work. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

World Health Organization (June 17, 2022). Mental Health.

World Health Organization (2022, 17 June).

Riegan, J. and Norriss, H. (2022, p.15).

Government Health and Safety Lead (2022, 21 June, p.1).

See: Business Leaders' Health and Safety Forum (2021, April).

Bennett, H. (2022, p.86).

See: Employment Hero (2022, n.d.).

Mental Health Foundation (2016, p.4).

Seitenbach, J. (2019, p.19).

Beyond Blue (2022, n.d.).

Seitenbach, J. (2019, p.11).

Mental Health Foundation (2024, n.d.)

WorkSafe (2020, 19 August).

Association of Consulting and Engineering (2021, 23 September).

Bennett, H. (2022, p.85).

Blackwood, K., D'Souza, N., Port, Z., and Tappin, D. (2022, p.115).

Fitzgerald, J. (2022, p.59).

Fitzgerald, J. (2022, p.57).

Cooper, V. (2022, p.107).

Bennett, H. (2022, p.86).

Dyhrberg, S. (2022, p.74).

Fitzgerald, J. (2022, p.59).

Blackwood, K., D'Souza, N., Port, Z., and Tappin, D. (2022, p.113).

Bennett, H. (2022, p.85).

Cooper, V. (2022, p.223).

Cooper, V. (2022, p.224).

Dyhrberg, S. (2022, p.79).

Fitzgerald, J. (2022, p.66).

Cooper, V. (2022, p.86).

Best, T., Visser, R., and Conradson, D. (2021, p.6).

Business Leaders’ Health and Safety Forum (2021, p.16).

SafeWork Australia (2020, p.5)

Bone, K., and Gardner, D. (2022, p.154).

Mental Health Foundation (2016, p.21).

McKinsey and Company (2023, p.2).

Government Health and Saferty Lead (2022, p.3).

See: Koutny, N. & Chatziadam, P. (2023).

Business Leaders’ Health and Safety Forum (2021, p.5).

Cooper, V. (2022, p.106).

Seitenbach, J. (2019, p.371).

Mental Health Foundation (2016, p.20).

WorkSafe (2022, p.10).

Bergefurt, A. G. M., Weijs-Perree, M., Appel-Meulenbroek, R., & Arentze, T. A. (2022, p.2).

Walker, M. (2022, p.1).

Great post, thank you for sharing, there's some top notch info in here. Well worth the read.