Managing Workplace Stress

April is Stress Awareness Month. Given the state of the economy and job cuts - and the threat thereof - across the public sector in Aotearoa, as well as the anxieties associated with the wider geopolitical context, the occasion is somewhat prescient. So, it's worthwhile revisiting the topic, especially what we can do if and when we find ourselves stressed at work.

In this post:

What is stress?

We tend to think of stress as a negative response to a challenging situation or unexpected event, such as being made redundant, losing your wallet, or running late for that important hui with your child’s teacher. In these types of situations, most of us experience similar symptoms like feeling irritable and/or flustered, our heart beats faster, you might get a headache; reading this, I’m sure you can immediately think of a recent example!

When it comes to workplace or work-related stress, these types of responses are very similar. But, regardless of the similarities between workplace and non-workplace stress, the concept is a bit more complicated.

Stress can be positive - sometimes called ‘eustress’ - or negative, which is sometimes referred to as ‘distress’. Some scholars refer to a continuum of a state of arousal (that is, how we respond to stress physiologically) with eustress and distress at either end.

The WHO provides a simple definition for the concept, suggesting it is “a state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation.”1

For workplace stress, Vanessa Cooper gives a slightly more expansive definition:

stress is understood as the physical, mental and emotional responses to unfamiliar, challening or complex work. It can be associated with thoughts and feelings of ‘not being able to keep up with, or have the right tools to cope with, the work demands placed on [workers]’ [sic]2

How common is workplace stress?

While stress is an accepted, normalised part of our everyday lives - who, for example, doesn’t feel some level of stress in their day-to-day life? - our experience of stress is becoming an increasing concern, especially at work.

WorkSafe, the Southern Cross Health Society, and Business New Zealand all identify a rise in workplace stress, “particularly so in office environments where workers are experiencing increased stress related to their work”.3

Last year, the Ipsos World Mental Health Day Survey reported:

Over half of [the 1,000] New Zealanders [who participated in the survey] said that they have felt stressed to the point where it had an impact on how they live their daily lives (64%) and felt stressed to the point where they felt like they could not cope / deal with things (57%) at least once in the past year.

In addition, Kiwis were more likely to report feeling so stressed they could not work (43%), compared with global compatriots (39% global average).4

Of particular concern are previous research findings suggesting:

Māori and Pasifika workers are disproportionally (negatively) affected by workplace stress. This is due to associated factors, such as institutional racism, and the high prevalence of Māori and Pasifika in less-secure, low-wage work, both of which are associated with higher stress levels.

Women may be more likely to experience workplace stress. In part, this is due to female employees’ higher experience of inappropriate behaviours such as bullying, discrimination and harassment. Another factor may be the lack of control women have in their work; women are often engaged in work with little to no decision-making latitude.

Unfortunately, women continue to bear the burden of undertaking a larger share of unpaid work - such as childcare - and continue to form the majority of domestic violence statistics; these factors result in a geneder imbalance of the experience of (negative) stress.

What causes stress at work?

While stress is a feature of our everyday lives, there are particular aspects of work that can increase the risk of us experiencing distress and, ultimately, harm.

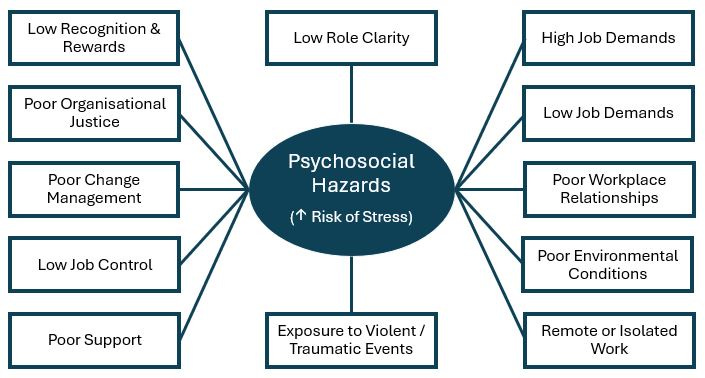

WorkSafe Victoria identifies several work-related psychosocial hazards that, while not necessarily acting as the cause of stress, can increase the risk of us becoming distressed at work.

Psychosocial hazards are factors in the design or management of work that increase the risk of work-related stress and can lead to psychological or physical harm…There is a greater risk of work-related stress when psychosocial hazards combine and act together, so employers should not consider hazards in isolation.5

The image below identifies common psychosocial hazards that can increase the risk of negative stress at work. It’s worth noting: many of these align closely with our understanding of what does and does not consitute mentally healthy work.

Given - in Aotearoa at least - the requirement of businesses to manage risks to workers’ health, safety, and well-being, it is important business owners, CEOs, and other managers focus on reducing the risk of their employees being exposed to such hazards at work.

What are the effects of stress?

Not surprisingly, positive and negative stress have corresponding positive and negative effects.

Eustress/positive stress

Eustress can challenge or mentally stretch us, motivate us, help us with problem-solving, and build our resilience. Positive stress can bring people together, strengthening social connections and acting as a protective factor for when eustress tips into distress. This type of stress is associated with a ‘growth’ mindset associated with learning and development, being open to feedback, greater collaboration, and innovation.

For workplace stress to remain positive and to avoid the harm associated with negative stress however, businesses, organisations, and managers need to ensure appropriate resources and supports are in place for workers who feel stressed.

Distress/negative stress

Work-related distress (which we generally call ‘stress’), is associated with a whole host of negative outcomes. These include:

Experiencing negative emotions, such as fear, anger, sadness, or frustration.

Changes in appetite, energy, desires, and interests.

Trouble concentrating and making decisions.

Sleeping difficulties, including nightmares and reduced sleep.

Physical symptoms (e.g., headaches, body pains, or stomach problems).

Contributing to non-communicable diseases (e.g., cardiovascular or respiratory disease, diabetes, and cancer).

Experiencing, contributing to, or exacerbating mental illness (e.g., depression or anxiety).

Increased substance abuse.

Often, when we’re experiencing negative stress, we experience many of these effects at once.

In addition, these symptoms can have downstream effects, often resulting in burnout, reduced job satisfaction, morale, motivation, and productivity.

Negative experiences can have wider effects on businesses’ performance and the wider labour market via increased absenteeism and presenteeism, reductions in employees returning to work (following illness-related absences), and early retirement/exit from work.

How do you identify a stressed worker?

Somewhat obviously, as individuals, we each - generally - have a good understanding of when we are experiencing eustress and when we might be tipping over into distress.

I should note that there is a strong disclaimer around *generally*; this isn’t true for everyone all of the time. Are you feeling on edge because you’ve got deadlines looming, your dog needs to go to the vet, and your car just failed its WoF? Or are you irritable because you feel - but can’t necessarily articulate - micromanaged by your boss, isolated from your colleagues, and undervalued by your employer?

To make matters even more complex, you might - like me - live with chronic mental illness, so *normal* stress is hugely different for each person.

Regardless of the complexities, there are some signs managers and colleagues can look out for. Drawing again from WorkSafe Victoria6, these include:

excessive emotional responses and erratic behaviour, such as uncharacteristic over-sensitivity, irritableness, or anger

obsession with some job elements while neglecting others

working longer hours than usual without the expected outputs, or working fewer hours

disengaging or withdrawing (e.g., a formerly social or extroverted employee suddenly becoming less social)

low morale, motivation, and/or energy levels

using negative language more frequently and/or entering into conflict with others more easily

appearing tired and experiencing headaches and/or frequent aches and pains

changes in physical appearance, such as less attention to personal grooming

reduced performance

How do you manage stress?

Negative stress, then, is something that needs to be carefully managed and, wherever possible, avoided via appropriate work design and support mechanisms.

While by no means exhaustive, here are some suggestions for how organisations, leaders/managers, and individuals can manage stress.

Know your employees/colleagues

Managers and colleagues need to invest time getting to know their staff/colleagues. Understanding what makes each other ‘tick’ - especially at work - and what particular triggers might be for individuals is key to being able to intervene early.

If you don’t know the people you work with, how will you effectively recognise the warning signs listed above?

The beauty of this is that investing this time - and, let’s be clear, across Aotearoa, businesses/organisations struggle with and/or avoid allocating time for doing so - has wider benefits. These include strengthening psychological safety, boosting staff morale, increasing job satisfaction, improving collaboration, lifting productivity, strengthening retention, and just overall making the workplace more positive.

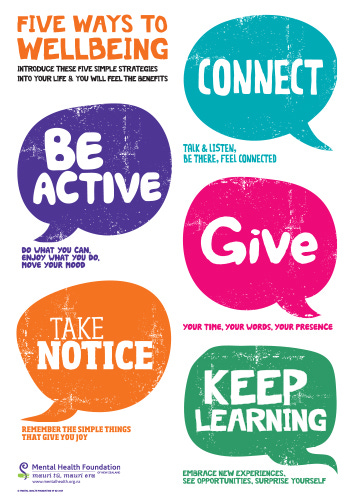

Practice the “5 Ways to Well-being”

For years now, the Mental Health Foundation has done a stellar job advocating the use of the 5 Ways to Well-being approach.

This evidence-based approach is comprised of five key strategies we can use in everyday contexts - and in a multitude of ways - to help reduce stress and support our overall mental health.

Connect/me whakawhanaunga - reach out and connect with people who are important to you, such as friends or colleagues

Be active/me kori tanu - do what you can to be active in your everyday life (e.g., taking the stairs or ‘deskercise’) and, if you can, engage in a physical activity that suits your mobility and fitness

Give/tukua - engage in acts of kindness, volunteer, give your time, attention, or acknowledgement

Take notice/me aro tonu - practice meditation, mindfulness, and pay attention to the present moment, your thoughts and feelings, and the world around you

Keep learning/me ako tonu - try something new, take on a new responsibility at work, explore a topic you’ve always wanted to know more about, or speak with a colleague or friend you know is a SME on a topic of interest; keep being curious

These strategies align with advice from the WHO and the Centres for Disease Control, who both identify all of the above strategies as methods for helping us cope with stress.

You can use these tools individually at work and home; managers can also work with their staff to explore how these strategies can be incorporated into everyday activities at work. As a bonus, employing these strategies will have general benefits for your mental health and well-being.

Practice healthy behaviours

Alongside the ‘five ways’ discussed above, to help reduce stress levels, it’s important you try to practice healthy behaviours including:

Eat well - aim to eat a balanced diet, balancing carbohydrates (and the all-necessary sugary treats!) with fruit, vegetables, and lots of water

Sleep well - try to maintain a regular routine, going to sleep and rising at the same time, avoiding hitting the 'snooze' button, and avoiding eating or drinking caffeine too late

Take your breaks - in New Zealand, we’re suckers for thinking that working through our lunch break or doing a couple of hours at the end of the day will help us. Spoiler alert: it won’t (especially in the long run). Take your tea break, use the whole hour for lunch, and clock off when you’re supposed to.

Engage in activities that bring you joy - most of us have activities we know help us feel better, whether it’s going to the gym, reading a book, watching a favourite movie, or - if you’re like me - doing some art; whatevever it might be, do the thing that helps take you to your happy place.

Avoid ‘doom scrolling’

Everyday, we’re bombarded with headlines and stories that can overwhelm us. If we’re already feeling vulnerable because of stress at work and/or home, this can be even more damaging.

To combat this, try limiting news exposure to a couple of times a day (or even week) and disconnecting from devices for a while. As long as you can stay connected with others via other means, you may even want to consider taking a break from social media.

Report it

As a former HSR and union Delegate, I know first-hand that we’re terrible at letting the right people know when we’re feeling stressed or encounter a problem at work.

While businesses have an obligation to support their employees’ health and well-being, this job is much harder if they don’t know that issues exist!

Use whatever lines of communication are in place to let managers and support staff know you are feeling stressed - especially if it is connected to one or more of the psychosocial hazards listed above. Leverage the H&S reporting system, speak with your manager and/or HSR, or - if you have it - discuss it during supervision.

Let people know you need help and how they can best support you.

What organisations can do

As I’ve mentioned a couple of times, in Aotearoa, businesses are legally required to protect and promote your health, safety, and well-being.

Under the Health and Safety at Work Act (2015), this means identifying potential hazards and risks that can create or exacerbate stress, implementing control measures to address those hazards and risks, and engaging with you - including seeking your input - on anything that may affect your health and/or safety.

Historically, when selecting and/or designing interventions to address workplace stress, businesses and organisations across Aotearoa have approached this at the lowest level of the hierarchy of controls. That is, reactive, individual-level strategies such as sending employees to EAP or similar services. While useful, this does not address the hazards that may be causing or exacerbating (dis)stress.

…agencies should not rely on tools at an individual level that may protect a worker when they are exposed to a risk; agencies should instead prioritise eliminating the risk at the source so far as is reasonably practicable.7

Organisation-wide strategies

As the figure below illustrates, there are many approaches buinesses can take to combat workplace stress, thereby meeting their legislative obligations.8

As with any and all strategies to effectively address to workers’ health and/or safety, a foundational approach is to promote active engagement and participation with employees.

Managers at all levels of an organisation need to take steps to meaningfully engage with their staff while promoting worker participation. While they are an important piece of the engagement puzzle, this needs to extend beyond consultation and engagement via Health and Safety Reps and Committees.

In addition, organisations should:

Consider developing an organisational policy and guidance on stress that, at least, includes definitions, assessment and reporting processes, information on roles and responsibilities, and available support services .

Strengthen workplace culture so that employees feel engaged, like they belong, their work is meaningful, they are valued and supported, are satisfied with and in their role(s), and that they can be themselves.

Focus on psychological safety whereby staff feel it is safe to

take risks, such as speaking up or admitting mistakes, without fear of punishment or humiliation.

Focus on eliminating or, failing that, minimising inappropriate behaviours including bullying, discrimination, and all forms of harassment.

Provide multiple formal and informal avenues for recognising employees’ contributions and rewarding staff for their mahi.

Provide multiple opportunities for staff to develop relationships and strengthen connections with colleagues across, between, and within teams.

Ensure there is access to support resources such as EAP/counselling, sick leave dedicated to mental health, return to work processes, and, where appropriate, supervision.

Provide a healthy work environment that protects and promotes workers’ health, safety, and well-being.9

Strengthen good work design be ensuring staff are well-matched to their roles, have autonomy and control, have access to training and development, can access flexible work options, and can safely access reasonable accommodations where required.

Leadership strategies

Research consistently highlights the importance of leaders’ behaviours in supporting workers’ health, safety, and well-being. When it comes to workplace stress, this is no different.

Leaders, managers, and supervisors in organisations are integral to the creation of psychosocial working conditions, but are also uniquely placed to buffer the impacts on their employees.10

In addition to their role in supporting the organisation-wide strategies listed above, all Leaders/Managers should:

invest time getting to know and understanding your direct reports - this will help them understand how your staff can be best supported

understand your own leadership style and how this might affect others’ stress levels

consistently demonstrate open, transparent, and honest communication (e.g., providing rationales for decisions and actions)

focus on feedback - invite it, give it, and learn how to provide and receive feedback appropriately and effectively

include staff in decision-making - seek their expertise, ask their opinion(s), and leverage their experience

actively promote and strengthen psychological safety (e.g., admitting when you’ve made a mistake, acknowledge others when they share ideas or constructively question decisions, and provide different avenues for sharing ideas and opinions) - make it safe for your people to speak up

work hard to always act in good faith while also applying policies and procedures consistently - don’t treat a team member differently just because you struggle to get on with them personally

follow-up on discussions and actions points - if you say you’ll do something, then do it, give staff timeframes for actions, be honest if you don’t know something (but do what you can to find out), check-in with staff after a ‘difficult’ or sensitive kōrero - in short, be kind

invest time in team-building (while remaining respectful and cognisant of your team members’ needs and preferences) and give lots of opportunities for your staff to connect as people; put effort into whakawhanaungatanga

encourage continuous improvement of processes and procedures - if someone identifies a more efficient process, see if you can adopt it; don’t be afraid to challenge the status quo just because “that’s how we’ve always done it”

Resources and support

If you’re feeling stressed - whether at work or elsewhere - you might find the following support avenues useful:

And, if you want to learn more about workplace stress, check out the resources below:

Healthy Work: Managing Stress and Fatigue in the Workplace (NZ)

Preventing and Managing Work-related Stress: A Guide for Employers (AUS)

Stress - National Center of Integrative and Complementary Health (US)

Bibliography

Bell, J. (2023, 3 February). Managing Workplace Stress and Fatigue.

Centers for Disease Control (2023, 25 April). Coping with Stress.

Cooper, V. (2022). “Stress - has it had a bad reputation?” In WorkSafe (Ed). Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.218-231. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

Employment New Zealand (2024). Stress Leave.

Fitzgerald, J. (2022). “Mentally Healthy Work: The Drive to Thrive”. In WorkSafe (Ed). Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.56-72. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

Government Health and Safety Lead (2021, May). Creating Mentally Healthy Work and Workplaces: A Guide for Public Sector Health and Safety Leaders and Practitioners.

Iposos (2023, 22 November). New Zealanders’ Views on Mental Health.

Mental Health Foundation (2022). Minimising and Managing Stress in the Workplace: The Implications of COVID-19. Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand: Wellington.

Mental Health Foundation (2024). Five Ways to Well-being.

National Center of Integrative and Complementary Health (2022, April). Stress.

NHS Employers (2022). Prevention and Management of Stress at Work.

Oakman, J., Lambert, K.A., Weale, V.P., Stuckey, R., Graham, M. (2023). Employees Working from Home: Do Leadership Factors Influence Work-Related Stress and Musculoskeletal Pain?. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 3046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043046

Pedersen J., Graversen B.K., Hansen K.S., Madsen I.E.H. (2024). The labor market costs of work-related stress: A longitudinal study of 52, 763 Danish employees using multi-state modeling. Scand J Word Environ Health. 50(2);61–72.

Walker, M. (2022, 27 September). Keeping Mentally Well.

Walker, M. (2023, July ). Spotlight on Mentally Healthy Work.

Walker, M. (2024, February). Spotlight on Psychological Safety.

Walker, M. (2024, February). Managing Psychosocial Risks at Work.

World Health Organization (2023, 21 February). Questions and Answers: Stress.

WorkSafe (2017, 12 November). Work-related Stress.

WorkSafe Victoria (2021, February). Preventing and Managing Work-related Stress: A Guide for Employers. WorkSafe Victoria: Geelong, VIC.

WorkSafe Victoria (2023, 9 May). Work-related Stress.

Yeats, J. (2021, 1 November). Lixin Jiang: How Leaders can Help Reduce Workplace Stress.

WHO (2023, 21 February). Questions and Answers: Stress.

Cooper, V. (2022). “Stress - has it had a bad reputation?” In WorkSafe (Ed). Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.218-231. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

WorkSafe (2017, 12 November). Work-related Stress.

Iposos (2023, 22 November). New Zealanders’ Views on Mental Health.

WorkSafe Victoria (2023, 9 May). Work-related Stress.

WorkSafe Victoria (2021, February). Preventing and Managing Work-related Stress: A Guide for Employers.

Government Health and Safety Lead (2021, May). Creating Mentally Healthy Work and Workplaces: A Guide for Public Sector Health and Safety Leaders and Practitioners.

For more detail on some of these approaches, see: Walker, M. (2023). Spotlight on Mentally Healthy Work.

For detail on office designs that promote workers’ health and safety, see: Walker, M. (2023, October). The Effects of Office Design on Workers’ Health, Safety, and Well-being: Findings and Lessons from Research.

Oakman, J.; Lambert, K.A.; Weale, V.P.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M. (2023). Employees Working from Home: Do Leadership Factors Influence Work-Related Stress and Musculoskeletal Pain?. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 3046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043046