Introduction

In March this year, Umbrella Wellbeing released its well-being report for 2025. This report explored the economic, organisational, and individual costs of presenteeism at work in Aotearoa. To build on this excellent mahi, this post explores the concept of workplace presenteeism.

I would like to acknowledge the work undertaken by Umbrella Wellbeing in undertaking this research and serving as the inspiration for this post.

In this article:

What is presenteeism?

Defining presenteeism is, it turns out, not as straightforward as one would assume.

Traditionally, scholars have taken the approach of defining it as a concept whereby presenteeism refers to “an employee who is physically present at work but absent in mind or behaviour”.1

Changes in technology and a shift in the way many of us work - largely brought about by the COVID-19 global pandemic - have brought the physical presence component of this definition into question. Staff who work from home while they are ill, for example, are not ‘physically present at work’ but are still engaging in presenteeism.

More recent definitions, then, have been expanded to accommodate this change in thinking.

Presenteeism is typically understood to be a behaviour that meets two conditions, namely that the employee must attend work (irrespective of the location), and that [sic] they must be physically or mentally ill, or at the very least, believe they are ill.2

Others suggest a more nuanced definition, suggesting it is a “goal-directed and purposeful attendance behavior [sic] aimed at facilitating adaptation to work in the face of compromised health.”3

Some authors stress the importance of considering positive effects of presenteeism in definitions so they “accommodate both productivity loss and potential productivity gain as well as non-illness related reasons.”4

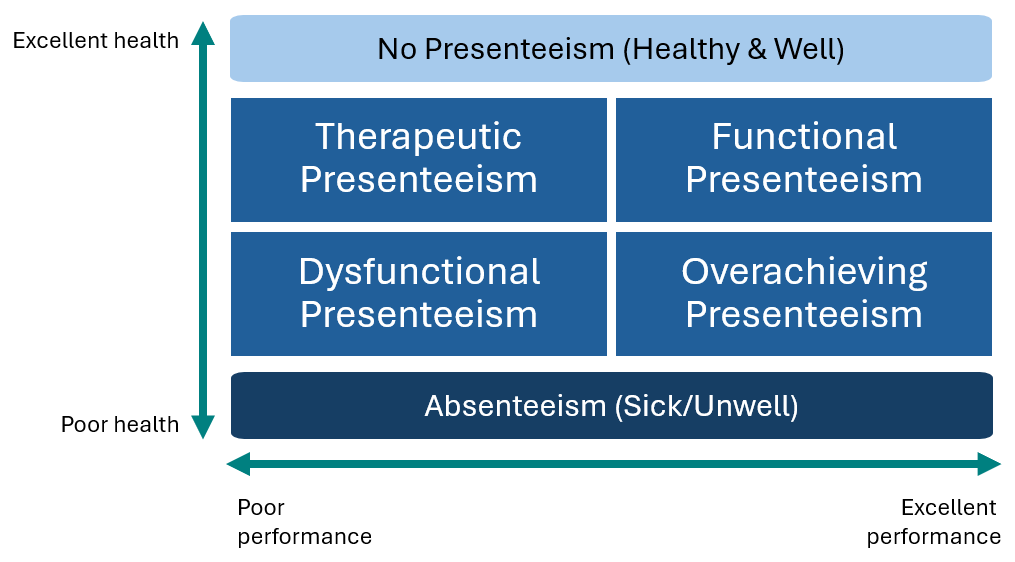

A model of presenteeism

While defining (and measuring) presenteeism is a fraught process, a popular framework of presenteeism has emerged in the literature. This framework proposes four distinct profiles or types of presenteeism.

In developing the framework, the authors argue that presenteeism is an adaptive behaviour, which seeks to balance health and performance.

As an adaptive behaviour, presenteeism is by nature a dynamic process: the four types of presenteeism are not fixed in time and possible trajectories between types depend on how presentees access and use resources to adjust to work demands and health impairments.5

Dysfunctional presenteeism

Dysfunctional presenteeism represents the most harmful type. It is a situation whereby sick workers choose to engage in presenteeism to the detriment of both their productivity/performance and their health and well-being.

Research suggests that, while health problems experienced by individuals aligning with this type are similar to overachieving peers, dysfunctional presentees demonstrate lower self-rated levels of performance. The same research indicates these individuals “report systematically higher exposure to all stressors compared to other profiles”6.

Crucially, research indicates that, for this group, there is a risk of a ‘downward spiral’ in which continuing to work when sick leads to further impairments of health and performance. This spiral can also feed into emotional exhaustion, as workers try to compensate for worsening health and/or performance.

Furthermore, because of the risk of this spiralling health and performance, the model’s authors note that this type of presenteeism can only ever be short-lived.

Overachieving presenteeism

When workers can maintain their normal level of performance (similar to, research suggests, functional presentees) while undermining their health and well-being, they are said to be engaging in overachieving presenteeism.

Researchers postulate these individuals may engage in this behaviour because of a lack of resources at home and/or due to workplace pressures, such as job demands or negative attitudes towards absenteeism.

Therapeutic presenteeism

Presenteeism is said to be therapeutic when workers focus on their health and well-being, but to the detriment of their work productivity/performance.

This group reflects the supportive nature of work, as individuals draw strength from the therapeutic value of engaging in work and spending time with colleagues and peers.

Some researchers suggest this type of presenteeism may be more widely seen among workers with mental illness or poor mental health, especially those with concerns about stigma and judgement from colleagues.

As with dysfunctional presenteeism, this type is typically short-lived, as the negative feedback and stigma garnered by on-going poor performance encourages workers to make a change.

Functional presenteeism

This type of presenteeism represents an ideal balance between performance and health. In other words, when someone is ill and they choose to work, they can maintain their productivity without negatively affecting their health and well-being.

Not surprisingly, individuals who fall into this category report less health problems and demonstrate a higher level of performance. However, some research results indicate these workers show similar levels of presenteeism as their dysfunctional and overachieving peers.

Key to the success of this type of presenteeism is the availability of resources that help workers achieve this ‘ideal balance’. Both internal and external resources - including a positive work environment and the provision of mentally healthy work - are vital to a health + performance balance.

What about remote work?

Changes in the way work is undertaken in many industries - largely driven by global events and technological advancements - have had a significant effect on our understanding of presenteeism.

[Remote work] has enabled workers to connect remotely, even when they are feeling less well, and even take time off due to their health conditions and without mentioning it to their line managers. The extent of presenteeism in the context of [remote work] may thus be underestimated.7

Some argue that, when workers are working from home or are undertaking similar remote work, there is an increased risk of presenteeism and that it can be more difficult for managers, leaders, and supervisors to identify when their staff are engaged in these behaviours. This increased risk is largely driven by:

a lack of need to travel to work

the reduced risk of spreading the illness among colleagues and/or customers

the flexibility afforded by remote work

implicit messages communicated by employers to “employees to ‘push on through’ while unwell if they can work from home”; and

reduced visibility to managers and colleagues, removing the need to justify or explain their decision-making

the introduction of new digital technologies has increased the risk of electronic monitoring and surveillance; workers’ fear of this risk may prompt workers to increase the frequency of presenteeism.

[Workers] may perceive their inputs and activities as extremely visible and under scrutiny, and therefore put in greater effort, which has been found to result in greater burnout. By intensifying the employees’ efforts at work, monitoring can promote a culture of being constantly available and generate feelings of attendance pressure, likely leading to working when sick.8

Importantly, some authors warn of the dangers associated with increased presenteeism seen amongst remote workers, many of which reflect the negative cost of presenteeism highlighted in research. In particular, the combination of limited social support from colleagues and managers and high job demands (especially those established by poor or inappropriate leadership practices) can result in:

reduced physical activity

social isolation and loneliness

poor work-life balance; and

procrastination (and, by extension, impaired productivity and performance).

Worryingly, low social support, high job demands, poor leadership, and a negative workplace culture (in which presenteeism is encouraged) reinforce “cumulative negative consequences (e.g., low well-being, anxiety, depression, burnout, loneliness, sedentary behavior [sic], and poorer sleep quality)” fostered by remote presenteeism.

Measuring presenteeism

A related difficulty with the phenomenon of presenteeism is that it is difficult to measure, with no standardised approach to doing so.

Often, researchers and businesses examine presenteeism from a position of the number of times staff go to work when they are ill and/or a perceived pressure (from managers or employers) to do so. The problem is, however, that presenteeism is a complex construct, with a range of factors coming into play.

Experts argue that any measure of presenteeism needs to reflect this complexity.

[Any] relevant measure of presenteeism needs to be able to distinguish between attendance motivation, propensity to engage in presenteeism behaviour as well as the act of presenteeism, to be able to shed light into the causes and consequences.

Understanding the effects of presenteeism, as well as the decision-making process, can be - from a research perspective - problematic because of measurement issues. As “there is no widely accepted measure of presenteeism”, different tools have been used to measure the phenomenon.

Because these tools differ in terms of content, response format, and the time period respondents are asked to reflect on, this makes comparisons problematic. Furthermore, while important, the subjective nature of measuring ill health adds further complexity.

How common is presenteeism?

Research indicates presenteeism is common in most countries.

It is a global phenomenon documented in many countries with prevalence reported to range from 30 to over 90% in different studies.9

One of the most striking aspects of presenteeism is its high prevalence across different countries and occupational groups.10

In Aotearoa, historical figures of presenteeism prevalence from a Gallup study put the phenomenon at 13% of employees. More recently, research highlights a rise in presenteeism (hitting 41.2% in 2024), while the report from Umbrella Wellbeing highlighted different rates of presenteeism for individuals working when mentally unwell (27%) and physically unwell (19%).

The majority of workers reported engaging in presenteeism at some point in the last month (87%).11

What does presenteeism correlate with?

Much work has been undertaken to identify the correlates of presenteeism.

On first blush, those who are generally unwell may be more inclined towards absenteeism, while those who are more fit more likely to engage in presenteeism. However, this is not borne out in research, as studies show “the less healthy are more inclined to both absenteeism and presenteeism”12.

Studies have highlighted that presenteeism is often correlated with a range of work-based factors.

Overall job demands, heavy workload, understaffing, and overtime are prominent correlates, as are uncivil interpersonal behaviours (abuse, harassment, discrimination), stress, and, particularly, burnout… [in addition to] working time arrangements… especially when a perceived gap between actual and desired working hours… [and] indirectly via the imposition of attendance pressure.13

Other work-related links with presenteeism include:

individuals’ job satisfaction

commitment to the organisation

engagement with work

job conditions (e.g., high workloads or high levels of stress)

work cultures - particularly in competitive sectors (e.g., hospitality); and

employment type - especially those with less secure employment (e.g., casual workers) and self-employed individuals.

Some work has examined the prevalence of presenteeism within specific industries. Although presenteeism is reasonably common across all industries, some - such as teaching, healthcare, and so-called ‘helping’ professions - appear to have higher rates. Researchers suggest this association is related to the nature of those professions and the populations they serve (i.e., concern for patients, the elderly, or tamariki).

A key observation here is that the industries in which presenteeism is more prevalent are, largely, female dominated. Correspondingly, the phenomenon is less evident in male-dominated industries, such as manufacturing or engineering.

A small body of research has looked at cross-cultural differences in prevalence. These studies have suggested higher rates of presenteeism in Latin countries and China, as well as those that provide more supportive provisions for sick leave and where “social welfare systems are relatively well developed”14.

What are the effects of presenteeism?

Whether online or in person, common sense would suggest that having staff at work when they’re ill would not have a positive effect. Certainly, most research has emphasised the negative cost of presenteeism.

More recently, however, authors have been calling for a more balanced view, arguing that presenteeism can have positive effects. As some definitions suggest, presenteeism is sometimes framed as an adaptive behaviour - especially in relation to remote work - implying a more positive view of the phenomenon and leading to increased expectations of ‘pushing through’ mild illness when working remotely.

Misconceptions of presenteeism as a solely negative behaviour increase the risk of mismanaged work, under-utilized [sic] capabilities, and attendance pressures…that can impede gradual recovery and return to work. Therefore, if managed well and supported with adequate resources, attending work during illness has the potential to benefit health and performance [their emphasis].15

Others note the co-occurrence of negative and positive effects, while some suggest “it is important that presenteeism is not viewed as an either positive or negative phenomenon, but rather as a trigger for a range of outcomes which have the potential to be negative or positive.”16

Negative effects of presenteeism

Various authors have identified different presenteeism costs to individuals and organisations. Importantly:

the adverse effects of presenteeism do not arise automatically, rather, they emerge when there is insufficient management or inadequate adjustments to work tasks, environment, or equipment.17

Productivity

When someone chooses to continue to work when they are ill, the most common ill effects are seen to be a reduction in productivity and performance.

Some research suggests that effects on productivity may vary according to the type of work being undertaken. One line of thought suggests task complexity is important, with performance of simple tasks being less affected by presenteeism than complex ones.

The degree of productivity loss, however, has been suggested to vary between workers, based on specific influencing factors.

[Research has] found that productivity loss during illness was lower for those with higher job security, for conscientious workers, and for those who could more easily be replaced at work when ill, whereas those with more pronounced neuroticism and higher family-to-work conflict reported greater productivity loss.18

In addition - and somewhat obviously - the nature of the illness can influence performance, with less severe illnesses putting a lower demand on workers, and some even taking the position “that not every health problem necessarily entails productivity losses”19.

Workers’ health

When staff choose to continue to work when they are ill, this can have a significant effect on their health and well-being, especially if not well-managed. Importantly, research highlights negative effects on both physical and mental health.

[Particular] health conditions such as allergies, hypertension, musculoskeletal pain, and mental health issues like anxiety and depression are strongly associated with higher rates of presenteeism and significant productivity losses.20

Such effects are related to:

depletion of resources (i.e., when workers go to work ill, their health deteriorates and their ability to recover is reduced)

increased stress related to feeling pressured to ‘show up’ when ill, potentially leading to emotional exhaustion and burnout

a need to engage in “sickness surface acting”21, in which a worker has to maintain the pretence of not being ill when undertaking tasks

this is especially common in public- or customer-facing roles, such as retail or hospitality; and

the negative effect of presenteeism on work-family conflict.

Importantly, if or when these elements work together, it can produce a spiral effect characterised by “a sustained spiralling loss of resources which [sic], in turn, can cause high levels of emotional exhaustion”22.

Employees’ health and well-being can also be directly influenced by negative organisational effects.

Employees experiencing presenteeism often suffer from depersonalization [sic], lower job satisfaction, reduced work ability, diminished work engagement, and increased emotional exhaustion…23

Organisational effects

The more often we choose to engage in presenteeism, the more severe the downstream effects.

In addition to a worsening of workers’ health and well-being and potential impacts on productivity, studies point to an increase in absenteeism - including long-term absenteeism - which, in turn, has a direct effect on teams and organisations.

Research also highlights “increased risks of workplace accidents and a greater likelihood of errors”24. These can affect organisations in several ways, including:

financial costs, such as lost revenue or inefficiencies arising from a need to correct errors

reputational damage

reduced morale and increased disengagement among workers

a decrease in productivity

disruptions to business operations (e.g., delays or system failures)

a potential increase in poor decision-making; and

potential legal and/or compliance risks.

In addition, of course, more accidents at work have a direct effect on workers’ health, safety, and well-being.

Recent research from Aotearoa highlights a range of specific, negative work-related effects for those who engaged in presenteeism. These included:

an impaired ability to enjoy work

struggling to handle work stress as well as they normally could; and

with regard to finishing tasks or achieving goals:

not having enough energy to do so

experiencing negative feelings about doing so

struggling to focus on achieving goals; and

not being able to complete difficult tasks.

Positive effects of presenteeism

Increasingly, research highlights some positive effects of presenteeism, with some suggesting that continuing to work when ill can be “therapeutic and functional”25. Positive effects of presenteeism include:

social benefits, such as being liked, demonstrating positive ‘citizenship behaviour’, avoiding isolation, maintaining career prospects, and showing loyalty

financial benefits (especially when calling in sick affects pay)

personal benefits, such as reinforcing one’s self-concept of resilience and endurance or strengthening feelings of accomplishment; and

role benefits, such as completing work tasks.

It’s argued that a key consideration is the role of work as a boon to workers’ health and well-being. In addition, engaging in work can support individuals’ recovery from ill health. From this perspective, presenteeism is viewed as a positive force, reinforcing the benefits of engagement with work, while also pushing back against negative outcomes associated with absenteeism, such as under-utilisation, isolation, and social effects (e.g., resentment from colleagues, exclusion from decision-making during absence).

Importantly, these positive effects can only be realised when presenteeism is managed correctly and there are appropriate supports - such as giving tasks to employees that align with their capacity when feeling unwell - in place.

[The] research states that the consequences of presenteeism can be positive if [my emphasis] adequate resources support some degree of flexibility and adjustment to work tasks, depending on the employee’s health status.26

Finally, it is important to note that:

any positive effects may be short-lived; and

even when workers’ experience of presenteeism is positive, frequent or longer periods of presenteeism can result in a worsening state of health and/or well-being and, consequently, increased absenteeism.

Costs of presenteeism

Alongside negative (and positive) effects of presenteeism, scholars have examined the financial cost of presenteeism to organisations and economies.

Various studies have identified that:

in Australia, presenteeism’s annual cost is approximately $34.1 billion

nurses’ presenteeism in the US has an annual cost of $12 billion; and

in the UK, there is a combined annual cost of absenteeism, presenteeism, and turnover of ₤53-56 billion, although presenteeism bears the lion’s share of this cost.

Many commentators suggest the cost of presenteeism is more significant than those associated with absenteeism.

[The occurrence of] presenteeism is up to 16 times more costly to employers in New Zealand than absenteeism.27

Research from Aotearoa suggests that the cost of presenteeism equates to a:

loss of just over a week of “productive days”

“monthly business cost of $2,032”; and

“up to $46.6 billion”28 annually.

In addition, other New Zealand-based research highlights the influence of other factors. A 2024 report examining the effects of bullying and harassment in Aotearoa identified that, in 2022, these behaviours resulted in rates of presenteeism with an annual cost of $369 billion. The authors of this report noted this estimate was “unlikely to capture the full extent of presenteeism-related costs”29.

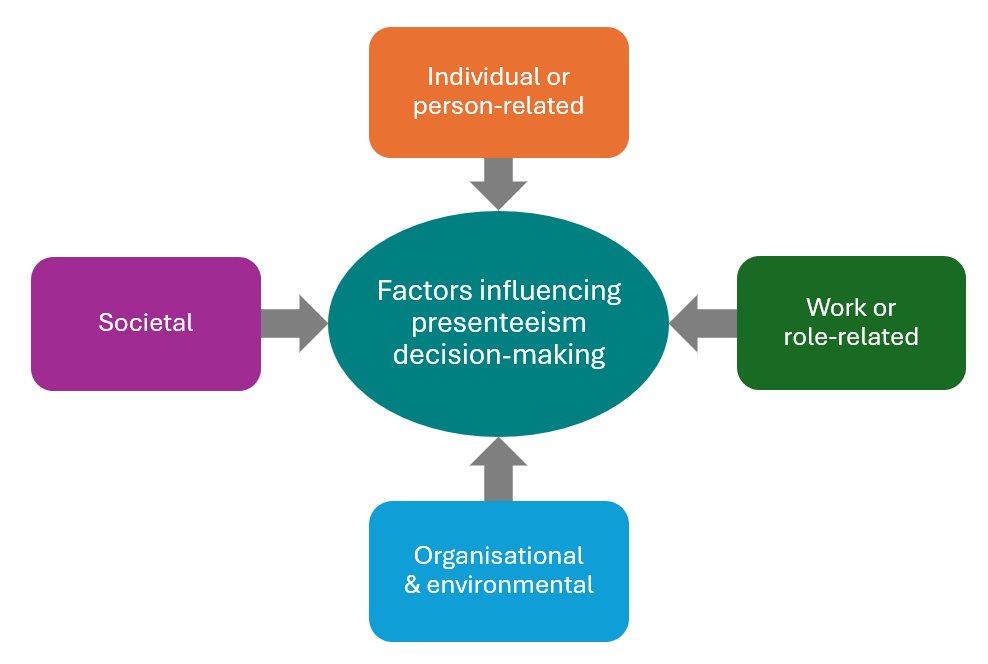

What influences presenteeism?

Over time, researchers have identified several factors that influence a worker’s decision to work when ill (or not). It is generally accepted that presenteeism behaviour is influenced by a complex interaction of factors to the extent that “workers with the same health problem could report different number of days of presenteeism and show different levels of performance”30.

There is a whole host of factors that come into play when deciding whether or not to work when sick. Importantly, these “can influence each other and can be contradictory to each other”31, making the decision-making process that much more difficult.

These factors also influence the type of presenteeism an individual may engage in. While they all have a degree of influence, authors identify two key factors.

[The] type of presenteeism enacted will be contingent on (1) the individual’s capacities or internal resources afforded by the health condition and (2) the flexible work resources available in the psychosocial environment and in organizational [sic] policies.32

Some research points to two particular factors that may have an out-sized influence on presenteeism:

social - especially collegial - support has been shown to act as a key resource, reducing stress and improving health and well-being; and

workers use leaders’ presenteeism behaviours as a model for their own behaviour (i.e., leaders engaging in presenteeism tacitly give their workers permission to do the same).

Individual or person-related factors

These factors are comprised of several elements, including:

personal values and attitudes, including someone’s “inner compulsion to work exceptionally hard”33

personality traits (e.g., conscientiousness or neuroticism)

psychological traits, including self-efficacy, health locus of control, and mental health

if someone perceives their ability to achieve goals through specific actions as high (high self-efficacy), they are more likely to demonstrate presenteeism behaviours; high self-efficacy can also act as a ‘buffer’, mitigating the risk of reduced productivity

an individual’s internal health locus of control reflects a “belief that one’s health is governed by internal factors”34 - this is associated with increased absenteeism and lower presenteeism (with a higher incidence of presenteeism seen among those with an external health locus of control)

a person’s ability to evaluate their symptoms during the ‘trigger’ stage of decision-making may be impaired if they are living with mental illness

work-family conflict

a worker’s commitment to mahi, as those with a higher degree of commitment to their work tend to increase presenteeism rates

level of job satisfaction, with less satisfied workers tending to choose absenteeism (over presenteeism)

individuals’ stress levels, as workers experiencing higher levels of stress are more likely to engage in presenteeism

the nature of the illness (e.g., how sick one feels, or how long we have been or expect to be sick, or how contagious the illness is)

demographics, such as gender, industry, and work-type (job security) have also been linked to differences in presenteeism rates

specific health conditions including depression, MSDs, and seasonal conditions; and

individuals’ level of financial stress.

Work- or role-related factors

Some authors suggest this group of factors has “a more decisive role”35 in the decision-making process.

Job demands have been identified as a key work-related factor. When demands - including psychological demands - are higher at work, workers tend to opt for presenteeism.

As noted earlier, social support is a significant driver in the decision-making process. Workers who feel they are better supported by colleagues and managers at work are more comfortable choosing to call in sick but, when the opposite is true, presenteeism becomes more common. Some research suggests that collegial social support may be more valuable than that provided by managers.

Autonomy, job control and decision-making latitude is another important element. In short, workers who feel as though they have little or no control and decision latitude are more likely to engage in presenteeism. Given its role as a component of mentally healthy work, research suggests this element may be the most important in protecting workers’ health and well-being.

As ever, leadership is a key antecedent. The influence of leadership on the decision-making process takes three main forms:

leaders’ behaviour providing a role-model for workers (i.e., when leaders model presenteeism, their staff tend to follow suit)

if a manager conveys an impression that they are suspicious of their employees’ sickness absence (sometimes called ‘supervision distrust’) those same workers are more likely to engage in presenteeism and may also experience other negative consequences

Presenteeism behaviors [sic] are a result of the perceived illegitimacy of sickness absence and may play an important role in increasing work-related emotional exhaustion.36

the leadership style managers apply in their mahi (e.g., a laissez-faire style increases presenteeism; a supportive style decreases the behaviour); and

the level of support leaders give their workers (e.g., encouraging staff to prioritise health and well-being).

A related concern is the relationship between workers and their manager. Some authors suggest that deciding whether to work when sick (or not) reflects “one’s desire to be more or less involved in a relationship with his or her supervisor”37. Similarly, the degree of psychological safety established in the employer-employee relationship is also important: when someone is ill, an open, honest, and safe relationship with their manager, for example, will likely lead to absenteeism.

As discussed above, the degree of job security a worker experiences is also reflected in presenteeism behaviours. The less secure an individual’s job, the more likely they are to work when sick. This means that temporary, casual, and fixed-term employees are more likely to engage in presenteeism than their peers with permanent, more secure roles.

Organisational and environmental factors

Alongside work- or role-related factors, there is a range of organisational factors that influence the decision-making process. Influencing organisational factors include:

workplace culture and organisational norms

as with leaders’ role-modelling, the degree to which presenteeism is normalised in a business or organisation - sometimes called ‘attendance pressure’ - strongly influences individuals’ decisions.

the psychosocial safety climate or PSC also has a role here as, according to this concept, instances of presenteeism should be low in a high PSC environment (because the organisation prioritises workers’ health and well-being above other considerations)

sick leave and attendance policies (and the associated HR practices)

more stringent and/or restrictive policies are more likely to result in a higher prevalence of presenteeism; and

the degree of organisational change

workers facing the threat of restructure and/or redundancies etc are more likely to engage in presenteeism behaviours.

Societal factors

Finally, wider societal factors may influence the decision-making process.

The economic climate may affect the prevalence of presenteeism in organisations, with times of financial difficulty leading to higher rates of presenteeism.

Changes in the way work is undertaken (e.g., the large shift to remote work seen with the COVID-19 pandemic) can affect the decision-making process. For example, higher rates of working from home can lead to higher rates of presenteeism.

Cultural differences and nationally driven attitudes and practices will also affect rates of presenteeism. Labour laws or cultural norms that discourage absenteeism, for example, may result in more presenteeism.

Individuals’ decision-making

The process for deciding whether to work when ill requires individuals to consider a range of external and internal factors or, as one group has described, “a complex and intricate network of forces”38.

Understandably, this is a complex, ever-changing, inconsistent, and intentional process. During this process, staff weigh-up the pros and cons of the potential effects to individuals, their team, and the wider organisation. Some authors have conceptualised this decision as a ‘fight or flight’ response. When they are ill, workers can choose to control (i.e., fight) or avoid (i.e., flight) the situation.

The decision-making process can be, it is argued, influenced by cognitive biases, including (but not necessarily limited to):

overconfidence bias or an inaccurate perception of control, with a greater sense of control leading to presenteeism

confirmation bias, in which seeing a colleague successfully navigating presenteeism reinforces that behaviour as a realistic option

social desirability bias, whereby people engage in presenteeism to appear dedicated or avoid judgement; and

a status quo bias, in which workers want to maintain a routine.

A key point to remember about individuals’ decision-making is that, when weighing up the pros and cons related to an instance of presenteeism, workers “tend to underestimate the potential long-term detrimental effects on their health”39.

A decision-making model

In 2023, a team of researchers from the UK presented a Presenteeism Decision-making (PDM) Model. This model presents the decision-making process as one comprised of four distinct stages.

The trigger stage is where an individual experiences the symptoms of their illness, starting the process.

During the options stage, the sick worker identifies the options available to them, and the factors that are relevant during this instance of ill-health.

The evaluation stage involves the process of weighing the pros and cons of each individual, work/role, organisational, and societal/cultural factor.

The final feedback stage is where the worker reflects on “the efficiency of their decisions against their health and performance demands”40.

As a model encompassing the full range of factors that influence the decision-making process, the PDM Model has been praised for highlighting the dynamic, spectrum-like nature of presenteeism, rather than a static, binary perspective.

How can we tackle presenteeism?

Organisations can adopt a range of strategies to combat presenteeism; not surprisingly, these align with some of the factors that influence the behaviour.

In their recent report, the team from Umbrella Wellbeing present an integrated framework for tackling presenteeism at work; some of these components are discussed further below.

Leadership

When managers adopt a positive, empowering style of leadership (e.g., ‘servant leadership’), staff are less likely to engage in presenteeism. Alongside this approach, managers can directly support workers by encouraging healthy behaviours and decision-making and supporting work flexibility (in both start/finish times and workload/responsibilities). Such support has been characterised as “a protective factor…[inhibiting] workers from attending work while ill.”41

[It] is essential for leaders to model healthy behaviors [sic] along with clarifying expectations and policies around sickness and attendance and promoting boundary-setting and mechanisms for switching off from work (including online communication) when sick.42

Relatedly, where present, senior managers need to work with their lower-tier and middle managers/leaders to eliminate behaviours and practices that signal supervisors’ distrust. This action goes hand-in-hand with establishing positive employer-employee relationships, strengthening psychological safety, and establishing a positive PSC.

Managers and leaders need to work on establishing and maintaining a positive, open relationship with their workers. This will not only facilitate their ability to apply a supportive leadership style but will also assist with encouraging workers to be honest in reporting illness and having conversations as part of the decision-making process.

[Leaders] have a role in identifying and supporting people with health conditions and help them to carry on with their responsibilities, or [sic] clarify and adjust their tasks if necessary.43

Resources

Workplace resources are frequently cited as important mechanisms for reducing presenteeism and/or mitigating its negative effects. When workers have support from managers, colleagues, whanau, and friends, for example, their performance when choosing to work when ill is significantly better than when this is low or absent.

As is often the case with workplace health and safety, robust, accessible policies and guidance are important for:

clarifying expectations

outlining options for temporal, spatial, and contract flexibility; and

where appropriate, outlining the degree of decision-making latitude workers have.

It’s crucial such resources are developed via bottom-up (rather than top-down) mechanisms that adhere to (at least) legislative requirements around engagement with workers. Finally, policies and guidance need to be supported by consistent practices that reinforce the business culture at all levels of the organisation.

While the efficacy of individual interventions to support mental well-being at work has, in recent years, been called into question, health and well-being programs can be a useful tool in reducing the risk of presenteeism. Given the relationship between presenteeism and workers’ physical and mental health businesses should, it is argued, look to health and wellness programs.

Culture

Alongside positive management and effective policies, to combat presenteeism, businesses need to consider the culture of the workplace. In particular, organisations should look to:

facilitate psychological safety to support conversations around the health vs. performance balancing act in the workplace; and

support autonomy, individual job control, and decision-making latitude.

A recipe for success

As with nearly all other elements of workplace health, safety, and well-being, the recipe for tackling presenteeism and ensuring those who engage in it adopt a ‘profile’ of functional presenteeism that involves an appropriate mix of support ingredients. This requires a coordinated approach within an organisation to ensure the business adopts an integrated model or, to stretch the metaphor further, carefully mixing the various ingredients to ensure the recipe turns out successfully.

[Businesses] should implement initiatives such as promoting self-awareness among employees, fostering a positive organizational [sic] culture, improving communication channels, monitoring presenteeism-related situations, and taking preventive or corrective measures. In this context, creating a supportive and harmonious work environment, ensuring equitable salary distribution and promotion systems, and offering opportunities for professional development are key elements of an effective approach to reducing presenteeism.44

To limit the negative effects and financial burden of presenteeism, businesses need to ensure managers (at all levels), teams, and individuals have the instructions needed to follow that recipe and, in doing so, ensure both healthy workers and a healthy organisation.

Bibliography

Biron, C., Karanika-Murray, M., Ivers, H., Salvoni, S., & Fernet, C. (2021) Teleworking while sick: A three-wave study of psychosocial safety climate, psychological demands, and presenteeism. Front. Psychol. 12:734245. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.734245

Biron, C., Karanika-Murray, M., & Ivers, H. (2022) The health-performance framework of presenteeism: A proof-of-concept study. Front. Psychol. 13:1029434. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1029434

Chen, H. (2024). Engaging in sickness presenteeism: How do people decide? The decision-making process behind sickness presenteeism, and implications for its management [Doctoral dissertation]. Nottingham Trent University: Nottingham, United Kingdom.

Cooper, C., Patel, C., Biron, M., & Budhwar, P. (2023). Sick and working: Current challenges and emerging directions for future presenteeism research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 44(6), 839-852. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2727

Correia Leal, C., Ferreira, A. I., & Carvalho, H. (2023). “Hide your sickness and put on a happy face”: The effects of supervision distrust, surface acting, and sickness surface acting on hotel employees' emotional exhaustion. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 44(6), 871-887.

Ferreira, A.I., Mach, M., Martinez, L.F., & Miraglia, M. (2022) Sickness presenteeism in the aftermath of COVID-19: Is presenteeism remote-work behavior the new (ab)normal? Front. Psychol. 12:748053. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748053

Fleming, W. (2023). Estimating effects of individual-level workplace mental wellbeing interventions: Cross-sectional evidence from the UK. University of Oxford Wellbeing Research Centre Working Paper, 2305. doi.org/10.5287/ora-yed9g7yro

Karanika-Murray, M. & Biron, C. (2020). The health-performance framework of presenteeism: Towards understanding an adaptive behaviour. Human Relations, 73(2), 242-261, doi: 10.1177/0018726719827081

Kişi, N. (2025). Analysis of presenteeism using a science mapping approach. Current Psychology, 1-16, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-025-07857-1

KPMG. (2024). Counting the Cost: Estimating the Economic Cost of Workplace Bullying and Harassment on New Zealand Employers. Wellington: Te Kāhui Tika Tangata New Zealand Human Rights Commission.

Lohaus, D. & Habermann, W. (2021) Understanding the decision-making process between presenteeism and absenteeism. Front. Psychol. 12:716925. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.716925

Masters, C. (2002, December 28). ‘Presenteeism’ attitude costing economy. The New Zealand Herald.

Mazzetti, G., Vignoli, M., Schaufeli, W.B., & Guglielmi, D. (2019) Work addiction and presenteeism: The buffering role of managerial support. Int J Psychol. 54(2):174-179. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12449

Priebe, J. A., & Hägerbäumer, M. (2023). Presenteeism reloaded – We need a revised presenteeism approach. Zeitschrift für Arbeits-und Organisationspsychologie A&O. 67 (3), 163–165

Ruhle, S. A., Breitsohl, H., Aboagye, E., Baba, V., Biron, C., Correia Leal, C., ... & Yang, T. (2020). “To work, or not to work, that is the question”– Recent trends and avenues for research on presenteeism. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(3), 344-363.

Tilo, D. (2025, March 12). Presenteeism rises: Employees clocked in, but not productive. HRD New Zealand.

Umbrella Wellbeing (2025). Presenteeism at work: Quantifying the cost to business in Aotearoa New Zealand of people working when unwell. Umbrella Wellbeing: Auckland, New Zealand.

Cooper et al. (2023, p.2).

ibid, p.5.

Karanika-Murray & Biron (2020, p.245).

Ruhle et al. (2020, p.7).

Karanika-Murray & Biron (2020, p.249).

Biron et al. (2022, p.12).

Biron et al. (2022, p.3).

Ferreira et al. (2021, p. 2).

ibid, p.2.

Chen (2024, p.10).

Umbrella Wellbeing (2025, p.9).

Ruhle et al. (2020, p.28).

ibid, p.29.

ibid, p.37.

Karanika-Murray & Biron (2020, p.244).

Ruhle et al. (2020, p.9).

Chen (2024, p.12).

Biron et al. (2022, p.4).

Ruhle et al. (2020, p.6).

Chen (2024, p.11).

Correia-Leal et al. (2023, p. 875).

ibid, p.881.

Kişi (2025, p.2).

ibid.

Ferreira et al. (2021, p. 6).

Ruhle et al. (2020, p.10).

Umbrella Wellbeing (2025, p.16).

ibid, p.10.

KPMG (2024, p.27).

Mazzetti et al. (2019, p.174).

Lohaus & Habermann (2021, p. 11).

Karanika-Murray & Biron (2020, p.251).

Biron et al. (2022, p.5).

Chen (2024, p.43).

ibid, p.37.

Ruhle et al. (2020, p.13).

Correia-Leal et al. (2023, p. 875).

Lohaus & Habermann (2021, p. 2).

Chen (2024, p.21).

Chen (2024, p.32).

Mazzetti et al. (2019, p.177).

ibid, p.3.

Karanika-Murray & Biron (2020, p.255).

Kişi (2025, p.13).