Context is Key: Exploring the Psychosocial Safety Climate

This article explores the concept of the psychosocial safety climate, its benefits, and what businesses can do to improve it.

Introduction

Internationally, it is acknowledged that poor health, safety, and well-being at work is a significant burden on individuals, teams, organisations, and societies at large. This burden takes many forms, including financially and, of course, as effects on individuals’ health.

A sub-set of this burden comes from the harm caused by psychosocial hazards and risks. While our understanding of these phenomena has increased, the burden of psychosocial hazards is also increasing. In part, this is due to organisations’ failure to effectively address such hazards and to ensure workers have access to mentally healthy work.

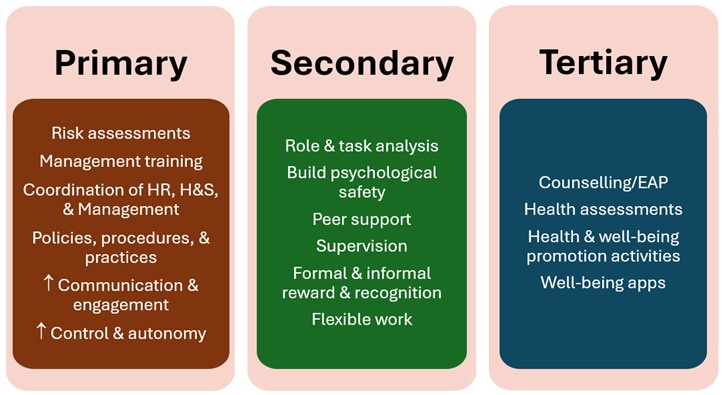

Time and again, research highlights employers’ on-going focus on reactive, tertiary level interventions – such as counselling services or access to health-related apps – that place responsibility at the feet of individuals. Instead, businesses need to put their resources into primary, organisation-level initiatives.

One such initiative is promoting and strengthening the psychosocial safety climate (PSC) of a business or organisation.

Contents

What is the PSC?

Fundamentally, the PSC is a high-level construct that reflects the value an organisation or business places on the psychosocial and mental health, safety, and well-being of its employees. When they introduced the concept in 2010, researchers Dollard and Bakker labelled the PSC as an organisation-level resource, stating:

PSC is defined as policies, practices, and procedures for the protection of worker psychological health and safety.1

Subsequent authors have broadened this definition to look at the PSC as employees’ shared understanding of an organisation’s approach to psychological health and safety and their perceptions of how their employer’s policies, practices, and procedures are enacted at work. In addition, others have added ‘organisational systems’ to Dollard and Bakker’s original list of the levers available for supporting psychological health and safety.

While it is understood to be a concept that relates to organisation-level activities, authors identify managers as key to understanding the PSC and suggesting that managers’ “values and beliefs”2 are the main driver of an organisation’s PSC.

“PSC is the way in which…management shows through what they say and do [sic] that stress prevention and mental health is a priority in the organisation.”3

Four components of the PSC

The PSC is typically conceptualised as a phenomenon that includes four main components:

Commitment, that is, how quickly and decisively managers act when an employee or group of employees raises concerns about psychological health and well-being.

Priority – the level of importance managers place on workers’ psychological health and well-being.

Participation – how well employees are supported and encouraged to participate in activities and decision-making related to their psychological health and well-being.

Communication – the effectiveness and frequency of communication between managers and their employees (that is, multi-directional) on psychological health and well-being.

These four components, it is argued, interact to form the PSC; if one element is low or poor, then the climate is negatively affected. A positive PSC, then, is one where:

managers are committed to, and demonstrably place a high priority on, workers’ psychological health and well-being

staff are actively encouraged to take up one or more multiple opportunities made available to participate in psychological health and well-being matters

importantly, without fear or experience of negative consequences; and

there is open, multi-directional communication, delivered via multiple, different channels, on psychological health and safety within the business.

PSC, demands, and resources

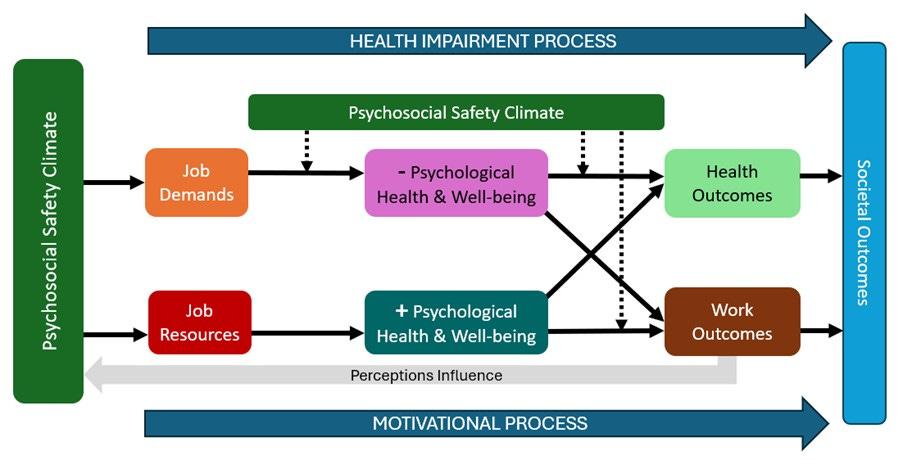

The concept of the PSC is closely aligned with the Job Demand-Resources (JD-R) theory, with the original authors presenting the PSC as an extension of the earlier JD-R model. That model – initially presented in 2001 – argues that demands (e.g., work pressures) and resources (e.g., autonomy) affect workers’ health via two processes:

a health impairment process in which “sustained effort to cope with chronic job demands leads to…negative responses”4; and

a motivational process whereby access to adequate resources leads to positive outcomes for individuals and the organisation.

Generally, a positive PSC is viewed as a resource, facilitating workers’ ability to cope with the demands placed on their roles at work. Conversely, a low or negative PSC can exacerbate the negative effects of demands at work.

However, at the same time, as a ‘cause of causes’, PSC precedes the health impairment and motivational processes.

PSC and management

Not surprisingly, managers are seen as key to the PSC. Some authors frame the PSC as something that reflects managers’ approach – rather than the organisation more generally – to the four elements of PSC discussed above.

Management has the power and position to enhance employees’ opportunities and use practical strategies to manage emotional demands. Managers possess the power and resources to implement these changes, and their commitment is important to any workplace policies targeting employees’ well-being.5

To put it simply, managers – especially senior managers – set the tone in the workplace; if these individuals are seen to not value workers’ psychosocial health and well-being, the PSC is already low.

As we’ve seen elsewhere, managers have a key role to play for improving psychological safety at work; this is linked to the PSC as, managers who support psychological safety are seen to demonstrate a greater commitment to workers’ psychological health and well-being.

In addition, research consistently shows a direct link between managers’ commitment to psychological health and an increase in employees’ demands at work. Similarly, the literature underscores the importance of managers’ support – especially that from senior managers – has in the effectiveness of interventions introduced at work.

It’s also worth considering that:

managers and leaders tend to rate the PSC higher than workers reporting to them, suggesting different understanding and/or experience of the PSC at a business; and

previous research findings have “found [the PSC] to protect managers from burnout and improve their quality of management.”6

Why is the PSC important?

Investment in workers’ mental health has been shown to have direct benefits for workers and organisations. In 2021, for example, the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research showed that organisations’ “focus on strengthening mental health at work…[has] a return on investment of $5 for every $1 spent”7. In addition, it brings downstream benefits including increased productivity, improved morale, decreased absenteeism and turnover, and benefits to workers’ health.

Within this wider context, research findings have underscored the importance of the PSC.

Improvements in PSC could save organisations with 5000 employees [sic] between 0.6 and 2.7 million US dollars annually.8

The PSC is viewed as both a lead indicator for, and antecedent of, psychosocial hazards and workers’ health in the workplace.

Empirical evidence shows that PSC is ‘a cause of causes’, a leading indicator of task-level job demands and job resources…and worker’s [sic] psychological health, as well as psychosocial safety behaviours.9

As well as the benefits discussed below, the PSC has been linked to specific workplace phenomena, including:

acting as a “social determinant of…bullying and harassment”10

“union density”11 (in Europe)

creativity and innovation (with a poor PSC leading to less creativity and innovation)

workers’ safety behaviours

worker engagement

interpersonal relationships

job design (with a poor PSC resulting in poor job design)

learning and development (with a high/positive PSC leading to greater engagement with development activities)

psychological safety or employees’ “voice behaviour [such as] conveying information for improvements or challenging the status quo”12; and

organisational justice.

It’s perhaps worth noting that research undertaken in 2018-2021 yielded findings that highlight the importance of the PSC, while also pointing to a moderate level of PSC in workplaces across Aotearoa, suggesting “that workers are at moderate risk of psychosocial harm…and…moderate risks for organisations”.13

Advantages and disadvantages

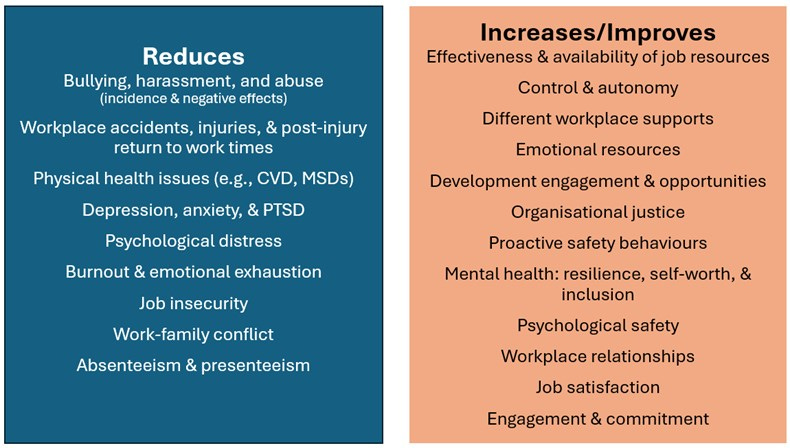

In the 15 years since the introduction of the concept of a PSC, research has unveiled many advantages and disadvantages associated with a high/positive and low/negative PSC (respectively).

Somewhat obviously, a high or positive PSC equates to an environment where the mental health and well-being of workers is valued and prioritised. Because of this, workers are protected from the negative effects of high job demands.

PSC has a significant and negative association with cognitive demands, psychological demands, emotional demands, quantitative demands, work intensification, work pressure, conflicting pressure, workload, long-working hours, hindrance demands, challenge demands and compulsive working.14

Businesses with a high or positive PSC

Where organisations fit into this category:

the effectiveness of job resources is improved, especially during difficult periods such as organisational change, restructures etc.

workers have better access to job resources, including:

“job control, decision authority, [and] decision influence”15

different levels of support (i.e., colleagues, managers, and the organisation)

emotional resources

opportunities for development

organisational justice; and

an increase in the “availability of secondary resources, such as supervision, training, and feedback”16

in terms of offensive behaviours in the workplace (i.e., bullying, harassment, and all forms of abuse):

the negative effects of these behaviours are reduced; and

the incidence of such behaviours is reduced and, in businesses with a very high PSC, these behaviours are eliminated

The research suggests that a 10 per cent increase in PSC within organisations would lead to a 4.5 per cent decrease in bullying, a 4 per cent decrease in demands, a 4 per cent reduction in exhaustion and a 3 per cent reduction in psychological health problems as well as an 8 per cent increase in resources and a 6 per cent increase in engagement.17

lower incidence of workplace injuries and accidents, along with an increase in positive/proactive safety behaviours

“PSC can directly promote safety behaviour, and can also indirectly influence safety behaviour through psychological resilience.”18

reduced incidence of physical health issues, such as circulatory disease or MSDs, – sometimes because of the role PSC has as a ‘buffer’ – and improved general health,

better mental health, including:

lower incidence of depression, PTSD, and psychological distress

improved resilience

higher self-worth

perceptions of improved psychological safety

better overall psychological well-being

moderating the effect of mental illness on workers

reduced incidence of burnout; and

stronger feelings of inclusion

improvements in social relationships at work

higher levels of job satisfaction

better engagement with and commitment to work

job insecurity is reduced

work-family conflict is reduced; and

reduced absenteeism and presenteeism

“if employees moved from [a] high/medium to low risk [sic] PSC…savings would be $1.18 million per annum based on reducing unplanned sickness absence”19

workers return to work more quickly after illness or injury.

Businesses with a low or negative PSC

Where organisations fit into this category:

the negative effects of job demands are more keenly felt by workers

job demands are increased

instances of “burnout, job strain, and emotional exhaustion”20 are higher

workers report more workplace bullying and harassment

earlier research yielded findings in which “bullying/harassment proved to be the most important factor linking PSC to psychological health problems.”21

there is an increased risk of mental illness, such as depression and suicidal ideation

higher absenteeism, presenteeism, and job turnover

workers are less engaged with their work and committed to their employer

higher incidence of workplace injuries and compensation claims

psychological safety is low, and workers are less likely to ask for help when they experience higher job demands; and

reduced productivity, innovation, and creativity.

How can a business measure the PSC?

By actively engaging with workers, businesses can measure the PSC within their organisation. As well as specific measures, businesses can leverage traditional risk assessment processes to understand “the gaps in existing psychosocial risk management systems… [by involving] all levels of the organization [sic] either directly or indirectly.”26

[The] number one thing that organisations must do to build mental safety is to get an accurate picture of wellbeing [sic] at work (and track how it changes over time). This means asking people regularly about their key challenges at work, what they are struggling with, and what’s working well.27

The development of the PSC concept/theory was quickly followed by the publication of research supporting an assessment tool, which businesses can use to assess the PSC.

The PSC-12 – developed by the research team of Hall, Dollard, and Coward (2010) – is a twelve-item questionnaire that has been shown to be a reliable, valid tool, which organisations can easily use to measure the PSC. This tool is divided into four sub-scales, comprised of three questions each, scored on a five-point Likert scale.

The scores derived from this assessment can indicate the ‘state’ of the climate in a business.

Scores of 41 or above places workers at low risk for poor health whereas scores 37 or below places workers at high risk for poor wellbeing [sic] outcomes such as job strain and symptoms of depression.28

How can a business improve the PSC?

There are a range of strategies businesses can leverage to improve the PSC in their organisation.

Importantly, wherever possible, interventions need to focus on prevention.

[Businesses’ approach to interventions needs to] shift from the individual level, where workers are viewed as responsible…to address the organisational and social working conditions in the organisation. Combining organisational level [interventions] and strengthening individual coping responses are advisable approaches [my emphasis].29

Tertiary (or individual) level interventions are easier and, often, cheaper, to implement, making them a ‘go to’ for many businesses across Aotearoa. However, findings from research highlight that such approaches “are likely successful at reducing thoughts and feelings of distress but [are] not helpful in changing the workplace climate [my emphasis].”30

As authors note, context is important and, consequently, improving PSC requires a significant focus on the organisation level. However, different intervention levels are not mutually exclusive; the best results will be derived from approaches that effectively balance and implement strategies at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels.

Before we take a look at specific strategies businesses can leverage, given the nature of the PSC, we first need to consider the influence managers’ hold in raising the positivity of this climate.

Managers’ influence

As noted earlier, managers have a key role to play, as:

managers’ commitment to and prioritisation of workers’ psychological health and wellbeing helps set the PSC; and

their support for interventions has a direct influence on the effectiveness of those interventions.

More generally, promoting the PSC is a core function of all managers’ roles. This involves:

prioritising the psychological health and well-being of their staff when designing roles, assigning tasks, and in their interactions with employees

promoting participation in activities and kōrero related to workers’ psychosocial health; and

providing multiple opportunities and methods for engagement and consultation with staff on any aspect of work related to workers’ psychosocial health.

To do this, managers need to have a clear understanding of:

what mentally healthy work is and looks like in their organisation

the psychosocial hazards and risks in their specific place of work; and

the demands associated with each role in an organisation.

At the same time, managers need to know and understand their staff as, benefits associated with a positive PSC are more or less evident depending on “the way interactions with team members are prioritised and actively participated in”.31

Importantly, managers cannot undertake this mahi in isolation:

employers need to give managers the resources (e.g., time, access to training, guidance collateral etc) they need to effectively perform these functions

senior managers need to “prioritize the job-related wellbeing of their line managers [sic]”32; and

managers need to collaborate, engaging in peer-reflection and co-learning that collectively lifts a business’ management capability.

Some research examining the use of management training to support psychosocial health and well-being has provided inconclusive findings, but recent research lends more support. A recent study, for example, demonstrated that improvements associated with training for managers remained in place 18 months post-intervention.

Our findings suggest that when PSC is medium to high, shorter training focusing on the importance of following the steps in the risk assessment process and ‘leader as a coach’ can improve PSC and psychosocial risks.33

Strategies to improve the PSC

Alongside the influence managers wield, there are specific strategies businesses can leverage to make this climate more positive.

Complete a risk assessment

While not an intervention in the traditional sense, it is important businesses invest resources into completing a risk assessment. Using the measurement strategies discussed above, businesses can get an understanding of the current state of the PSC.

Importantly, this needs to be an on-going process in which manages use formal and informal tools as and after interventions are implemented.

Develop policies and procedures

Businesses need to engage with staff to develop policies and procedures that promote a positive PSC. Such resources need to be clear and accessible for all staff.

Importantly, these cannot be:

left to stand alone – there needs to be clear practices, role-modelled by managers, that support such resources, and which articulate how staff are expected to ‘live’ the principles set out in policies; and

[E]spoused policies are not enough to create real change. It is necessary to enact policies and practices to successfully create change.34

treated as a ‘once and done’ activity – businesses need to be proactive about reviewing such resources, ensuring there are clear pathways in place for staff to give feedback, as well as continuous improvement processes to ensure policies etc remain fit-for-purpose.

Adopt a ‘joined up’ approach

Managers need to work with staff employed in human resources and health and safety to ensure they adopt a consistent, collaborative, and ‘joined up’ approach that promotes and protects workers’ psychological health and well-being.

Effectively, there needs to be a shift from psychosocial risk management perceived as an HR and/or health and safety function to becoming “a critical strategic management…initiative”.35

[Organisations’] executive teams [need to] reduce bureaucratic control, transitioning from efficiency and capitalism-drive approaches to ones emphasizing [sic] employee compassion… Leaders should foster autonomy, recognition, and personal growth opportunities for employees to promote workplace safety from a psychological perspective.36

Strengthen psychological safety

For some, the PSC reflects the level of psychological safety within a business while the original authors who put forth the concept viewed the PSC “as an antecedent to Edmonson’s psychological safety construct”37.

Regardless, it’s fair to say that a business with a high/positive PSC will likely have a correspondingly high level of psychological safety.

Organisations prioritizing psychological safety, often indicated by high PSC, are likely to provide crucial resources for employees' well-being.38

Building an environment in which employees can safely share their views, ask questions, and challenge the quo is one way that managers demonstrate their commitment to and prioritisation of workers’ psychological health and well-being.

There are many avenues open to businesses to improving psychological safety at work.

Facilitate communication and engagement

As we’ve seen, a key component of the PSC is communication. In line with requirements under current legislation, it is important for businesses to establish multiple channels for staff to participate and engage in multi-directional communication (i.e., top-down, bottom-up, and horizontally).

This includes (but is not limited to) ensuring:

staff have accessible communication and engagement methods and can choose methods that meet their needs and preferences.

there is facility for providing anonymous feedback

there are processes in place for actioning and responding to feedback (e.g., staff should know what has happened to their feedback)

opportunities are provided in hui and other kōrero for staff to safely engage in communication; and

staff have opportunities to contribute to decision-making related to how their psychological health and well-being is supported at work.

Provide mentally healthy work

Mentally healthy work is a complex concept, comprised of many different aspects that need to be supported to protect and promote workers’ health and well-being.

In the context of the PSC, there are particular elements of mentally healthy work businesses should focus on. These include:

Ensure workers have access to flexible work arrangements, including different options for location, hours, and schedules (e.g., a nine-day fortnight).

Research suggests approaches such as a four-day working week (while retaining five-days’ pay) see significant improvements in PSC.

Ensure staff have a reasonable degree of control and autonomy in their roles. This includes:

supporting management/leadership approaches that facilitate autonomy (e.g., ‘servant’ leadership or avoiding micro-managing and authoritative leadership)

allowing staff to engage in decision-making for their role and – especially – matters related to psychological health and well-being.

Give staff – including, especially, managers – access to training and resources that improves their knowledge and understanding of the PSC and mentally healthy work.

Establish multiple avenues of support for staff that includes access to:

counselling (e.g., EAP)

peer and professional supervision

training and development opportunities

formal and informal pathways for reward and recognition.

Its role as the ‘cause of causes’ for psychological health and safety at work means the PSC has the potential to significantly improve workers’ health and well-being and, in doing so, deliver positive outcomes for businesses.

“To accomplish a PSC, measures to improve working conditions and mental health should be implemented in a coordinated approach that includes organizational communication, management involvement and commitment [sic].”39

Achieving this, however, requires a significant investment from businesses to leverage risk assessment and multi-level interventions that are fit-for-purpose for their organisation because, as we know, context is key.

Bibliography

Amoadu et al. (2023). Influence of psychosocial safety climate on occupational health and safety: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 23:1344. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16246-x

Andersen, L.P.; Andersen, D.R.; Pihl-Thingvad, J. (2025). Psychosocial Climate as Antecedent for Resources to Manage Emotional Demands at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 22, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010064

Australian Research Council/Centre for Workplace Excellence (2023). What is Psychosocial Safety Climate? University of South Australia: Adelaide, AU.

Bailey, T. S., Dollard, M. F., & Richards, P. A. M. (2015). A national standard for Psychosocial Safety Climate (PSC): PSC 41 as the benchmark for low risk of job strain and depressive symptoms. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(1), 15-26.

Bailey, T., & Dollard, M. (2019). Mental Health at Work and the Corporate Climate: Implications for Worker Health and Productivity. Adelaide, Australia: University of South Australia.

Berglund, R. T., Kombeiz, O., & Dollard, M. (2024). Manager-driven intervention for improved psychosocial safety climate and psychosocial work environment. Safety Science, 176, 106552.

Berglund, R. (2025). Building Psychosocial Safety Climate and Conditions for Employee-Driven Innovation (PhD dissertation, Mälardalens universitet). Retrieved from https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:mdh:diva-69623

Blackwood, K., D'Souza, N., Port, Z., and Tappin, D. (2022). “Psychosocial factors: Pathways to harm and wellbeing”. In WorkSafe (Ed.) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand, pp.112-130. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand.

Bouzikos, S., Afsharian, A., Dollard, M., & Brecht, O. (2022). Contextualising the effectiveness of an employee assistance program intervention on psychological health: The role of corporate climate. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5067.

Dera, A. K., Adedokun, M. W., & Iyiola, K. (2025). The Psychosocial Safety Climate’s Influence on Safety Behavior and Employee Engagement: Does Safety Leadership Really Count? Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 179.

Dollard, M. F., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 579-599. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X470690

Dollard, M. F. & McTernan, W. (2011). Psychosocial safety climate: a multilevel theory of work stress in the health and community service sector. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 20(4), 287-293.

Dollard, M. F., Bailey, T., McLinton, S., Richards, P., McTernan, W., Taylor, A., & Bond, S. (2012). The Australian workplace barometer: Report on psychosocial safety climate and worker health in Australia. Safe Work Australia: Canberra, ACT.

Dong, R. K., & Li, X. (2024). Psychological safety and psychosocial safety climate in workplace: A bibliometric analysis and systematic review towards a research agenda. Journal of Safety Research, 91, 1-19.

Forsyth, D., Ashby, L., Gardner, D., & Tappin, D. (2022). Psychosocial safety climate and worker health: Findings from the 2021 NZ Workplace Barometer. Massey University: Palmerston North, NZ.

Government Health and Safety Lead (2023). “Notes from 28th September 2023”. In Mentally Healthy Work Community of Practice: 2023 Summary Notes. GHSL: Auckland, NZ.

Hall, G. B., Dollard, M. F., & Coward, J. (2010). Psychosocial safety climate: Development of the PSC-12. International Journal of Stress Management, 17(4), 353.

Idris, M. A., Dollard, M. F., & Tuckey, M. R. (2015). Psychosocial safety climate as a management tool for employee engagement and performance: A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(2), 183.

Kamil, N. L. M., Stillwell, E., Nordin, W. N. A. W. M., & Zhao, K. (2024). The Longitudinal Effect of Psychosocial Safety Climate and Employee Voice Behaviour: Does Job Crafting and Paradoxical Leadership Matter? In Opportunities and Risks in AI for Business Development: Volume 1 (pp. 875-885). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Law, R., Dollard, M. F., Tuckey, M. R., & Dormann, C. (2011). Psychosocial safety climate as a lead indicator of workplace bullying and harassment, job resources, psychological health and employee engagement. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43(5), 1782-1793.

Loh, M. Y., Dollard, M. F., & Friebel, A. (2024). Economic costs of poor PSC manifest in sickness absence and voluntary turnover. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 1-14.

Loh, M. Y., Dollard, M. F., McLinton, S. S., & Brough, P. (2024). Translating psychosocial safety climate (PSC) into real-world practice: two PSC intervention case studies. Journal of Occupational Health, 66(1), uiae051.

Looi, J. C., Maguire, P. A., Kisely, S., Allison, S., & Bastiampillai, T. (2024). Psychosocial workplace safety in mental health services – Commentary and considerations to improve safety. Australasian Psychiatry, 32(6), 558-562.

Omorede, A., & Berglund, R. T. (2024). The level of burnout and cognitive stress in managers when teleworking: the impact of psychosocial safety climate and the mediating role of demand-control-support. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 17(3), 220-240.

Rathnayake, G. U. P., Chandrakumara, A., & De Zoysa, A. (2023, November). Bridging efficiency and empathy: The role of psychosocial safety climate in mitigating emotional stress in lean manufacturing environment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management. Anais... Michigan, USA: IEOM Society International (Vol. 14).

Taibi Y, Metzler YA, Bellingrath S, Neuhaus CA and Müller A (2022). Applying risk matrices for assessing the risk of psychosocial hazards at work. Front. Public Health 10:965262. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.965262

Umbrella Wellbeing (2024). Mental safety at work: Tackling the biggest mental health risk – and opportunity – for organisations in 2024. Umbrella Wellbeing: Auckland, NZ.

Walker, M. (2016). Psychosocial Safety Climate: An Introduction. [Unpublished resource]

Winwood, P. C., Stevens, F., & Bowden, R. (2013). The role of psychosocial safety climate in job stress and work-related injury: observations of the Australian aged-care industry. Occupational Medicine and Health Affairs, 1(135), doi: 10.4172/2329-6879.1000135

WorkSafe (2023). A Psychosocial Survey of Healthcare Workers. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

Zadow, A. J., Dollard, M.F., Dormann, C., & Landsbergis, P. (2021). Predicting new major depression symptoms from long working hours, psychosocial safety climate and work engagement: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 11: e044133. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044133

Zhao, W., & Li, S. (2024). How does psychosocial safety climate affect safety behavior in the construction industry? A cross-level analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1473449.

Dollard & Bakker (2010, p.580).

Hall et al. (2010, p.356).

Berglund (2025, p.23).

Dollard & Bakker (2010, p.581).

Andersen et al., (2025, p.11).

Berglund (2025, p.23).

Umbrella Wellbeing (2024, p.4).

Berglund (2025, p.24).

Loh et al., (2024, p.636).

Law, et al. (2011, p.1791).

Loh et al., (2024, p.636).

Kamil et al, (2024, p.2).

Blackwood et al, (2022, p.126).

Amodau et al., (2023, p.5).

ibid

Andersen et al, (2025, p.4).

Bailey & Dollard (2019, p.7).

Zhao & Li (2024, p.6).

Bailey & Dollard (2019, p.10).

Amodau et al., (2023, p.6).

Law et al., (2011, p.1790).

Zadow et al., (2021, p. 9).

Bailey & Dollard (2019, p.12).

Loh et al., (2024, p.641).

ibid

ibid, (p.2).

Umbrella Wellbeing (2024, p.12).

ASC/Centre for Workplace Excellence (2023, p.2).

Berglund, (2025, p.24).

Bouzikos et al, (2022, p.10).

Berglund, (2025, p.67).

Omorede, (2024, p.234).

Berglund et al., (2024, p.13).

Loh et al., (2024, p.2).

Berglund et al, (2024, p.3).

Dong & Lai, (2024, p.12).

Dollard & Bakker, (2010, p.580).

Kamil et al., (2024, p.3).

Taibi, (2022, p.14).