Spotlight on Workplace Bullying

Exploring workplace bullying, its prevalence in Aotearoa/New Zealand, its effects, prevention strategies, and control measures

The Mental Health Foundation’s annual Pink Shirt Day appeal - an event focused on raising awareness of bullying in all its forms and contexts - is set to take place later this week; it serves as a timely reminder for understanding workplace bullying.

Internationally, the prevalence of employees’ experience of workplace bullying is said to be 15%. Recently, the Business Leaders’ Health and Safety Forum shared that, in Australia, workplace bullying and harassment is a little over 20% of all serious mental injury claims.

Decades of research has shown the significantly negative effects workplace bullying has on victims and witnesses.

Together, this highlights the importance of understanding workplace bullying, its effects, and what we can do to minimise and respond to it.

Contents

If you or someone you know is or has been affected by bullying at work, please refer to the resources below for where you can access information and support.

What is workplace bullying?

Defining Bullying

Defining workplace bullying is no simple task; researchers have struggled to agree on a consistent definition, although, in Aotearoa New Zealand, WorkSafe has offered a definition as part of its guidelines to support businesses and their leaders.

Workplace bullying is repeated and unreasonable behaviour directed towards a worker or a group of workers that can lead to physical or psychosocial harm.1

The various elements that make up this definition - repetition over a period of time, targeting one or more workers, and the significant, negative effects on recipients' health and well-being - are echoed in work undertaken by many researchers.

However, other researchers provide a different perspective. Explorations of workers’ experience of bullying identifies that, particularly for victims, single or one-off incidents can be "just as humiliating and damaging".2

Some studies have examined the occurrence of workplace 'incivility' - described as "a subtle form of interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace, consisting of rude behaviours [and] low intensity aggression"3 - as a precursor to workplace bullying.

One argument is that repeated acts of incivility increases the likelihood of bullying; over time, uncivil actions become more systematic and escalate into bullying, resulting in greater harm.

Which behaviours might not be bullying?

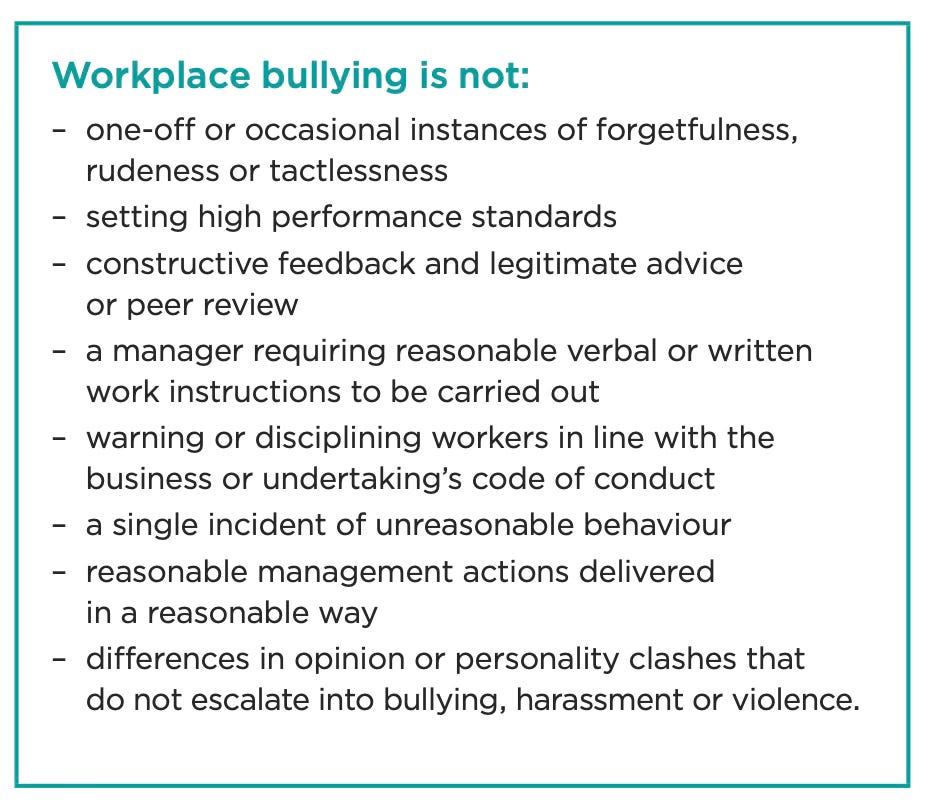

A useful way to understand workplace bullying is to consider what workplace bullying is not. WorkSafe offers useful guidance here, explicitly identifying behaviours that may not be considered to be workplace bullying.

While individual instances of these behaviours might not constitute bullying, these behaviours are examples of incivility; therefore, they should be considered a ‘red flag’ for businesses. Importantly, these types of behaviours can have a significantly detrimental effect on victims' health and well-being and should be addressed appropriately (e.g., providing support for victims).

An important consideration is that there can be some 'blurring' of the lines in terms of what constitutes workplace bullying because of factors related to the culture of the workplace.

Different workplaces may also have norms that are part of their culture such as friendly banter or rites of passage when joining the organisation. These practices may be acceptable when they are designed to strengthen and include, and can assist new workers to become part of the group. However, if left unchecked over a period of time, these practices can become targeted or exclusionary and could be considered bullying.4

Therefore, addressing issues related to work culture is a key action workplaces, leaders, and other employees can take to prevent and respond to bullying.

Types of bullying

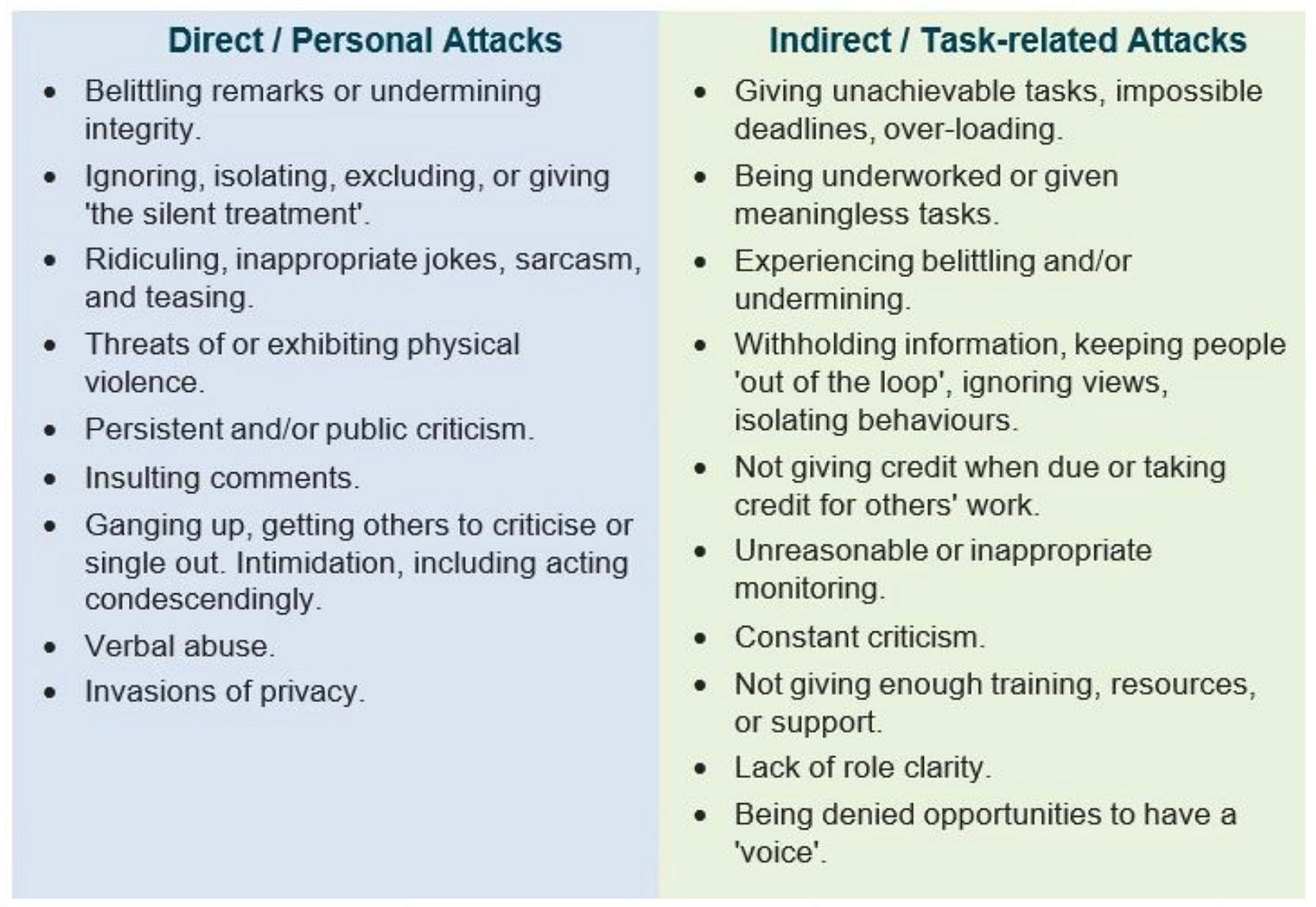

Different commentators point to different types of bullying behaviours, that can be delivered in different ways, including face-to-face, electronically/digitally, and/or via third parties.

Some commentators suggest the most common bullying behaviours can be categorised into two main groups:

direct or personal attacks; and

indirect or task-related attacks.

Examples of behaviours that fall into these groups are shown below.

Bullying can sometimes be difficult to identify and may often be mis-categorised as ‘reasonable’ reactions to a specific context when, in fact, they signal the start of a series of behaviours against an employee that results in significant harm for that individual and, potentially, witnesses and the wider organisation.

Although bullying is often understood as or perceived to manifest as explicit aggressive behaviour, it usually will take more subtle forms. Much bullying as experienced is understated and insidious. Bullying behaviours can be conducted in secret and can include passive actions, such as excluding [staff ] from meetings...5

Bullying categories

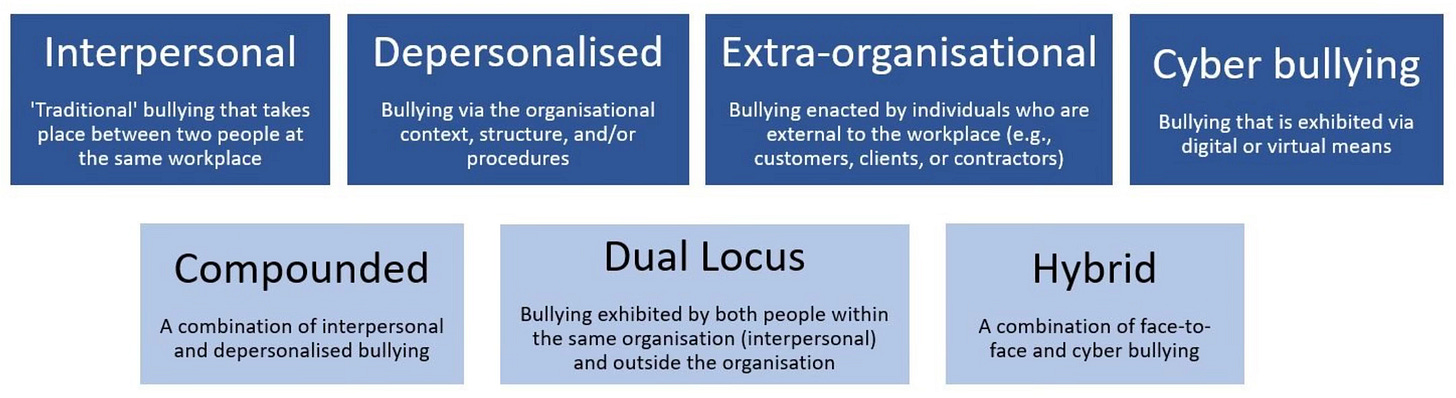

In addition to the types of bullying behaviours discussed above, some suggest there are seven different categories.

The consistent feature of all types and categories of bullying is that they involve one or more parties engaging in negative behaviours that have wide-reaching effects on victims and bystanders.

Regardless, the status of bullying as a widespread problem in workplaces across Aotearoa means that businesses and their leaders must take action to prevent, reduce the risk of, and respond to bullying and its associated harm.

How prevalent is workplace bullying in Aotearoa?

Estimates of the prevalence of bullying in workplaces across Aotearoa vary.

Some research suggests 11-20% of workers have experienced or been affected by workplace bullying.

However, WorkSafe's 2021 survey of over 3,000 workers found that, in the year leading up to the survey, the percentage of staff who experienced or were witness to bullying and cyberbullying was 23% and 16% respectively.

A 2022 survey from the Human Rights Commission found that 40% of respondents reported being bullied at some time in their working life, and reported that "one in five workers have experienced workplace bullying in the last 12 months".6

The same research also demonstrated that nearly "half of workers (44%) have either observed workplace bullying, were told by someone that they were bullied in the workplace, or heard about someone who was bullied in their workplace."7

Even more recently, research from Professor Jared Haar (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Mahuta) indicates a much more distressing picture. These results showed bullying in the workplace is highly prevalent, with only 8.6% of employees reporting they have never been bullied, while 24.2% say that on average, they experience bullying monthly. The highest frequency of bullying - where employees face it weekly or more - sits just under 10%.

This research also demonstrated that:

16% of male and 8% of female employees were more likely to be in the high bullying frequency group

workers aged 36-40 and 41-45 are most likely to experience workplace bullying and/or harassment

differences are seen in occupations, with the following having more than 25% in the high bullying frequency group:

skilled animal and horticultural workers

farmers and farm managers, and farm, forestry, and garden workers

food trade workers

arts and media professionals

design, engineering, science and transport professionals; and

sports and personal service workers.

Regardless of the source, then, research consistently highlights that workplace bullying in Aotearoa is a significant and widespread problem.

Who are the victims of bullying?

As the findings discussed above identify, the literature identifies some clear trends around which employees are subjected to bullying, with some studies indicating a higher incidence of bullying for specific groups, such as women, older workers, Māori, or people with disabilities.

It's important to note, however, that results from research exploring individual characteristics of bullying victims vary across several factors.

In addition to specific individuals or groups, research has indicated that while rates of bullying vary across industries, workplace bullying has been shown to be "more prevalent in large organisations...in public sector organisations...and organisations that are male-dominated".8

Often, bullying is understood as a power imbalance between two or more parties. However, this does not mean that workplace bullying is solely a top-down phenomenon; it is seen at all levels and can occur as a top-down, bottom-up, equal-level, and bi-directional process.

What are the antecedents of workplace bullying?

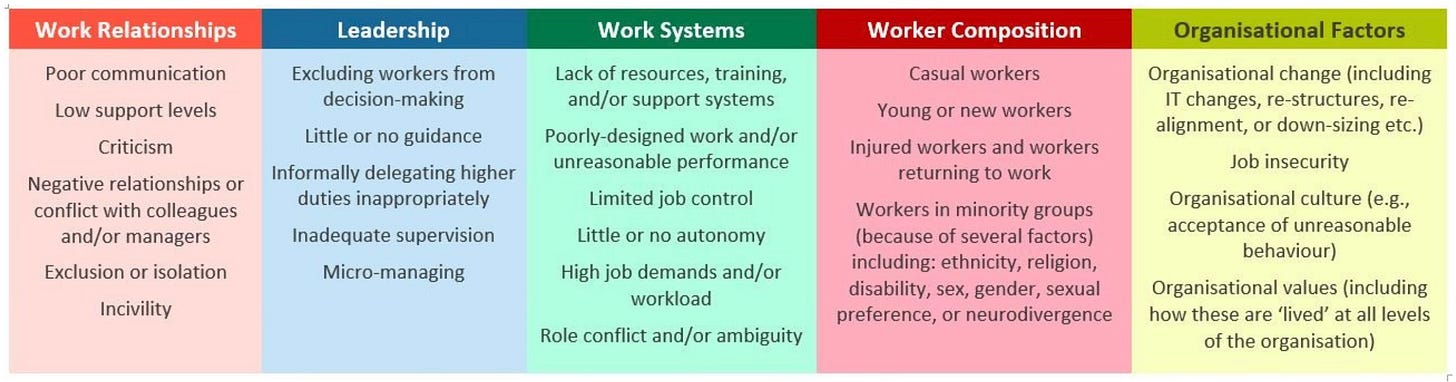

Various studies have identified a range of factors or antecedents that can affect workplace bullying or which enable bullying to flourish. Broadly, these can be divided into organisational-level and individual-level antecedents.

Organisational-level antecedents

Seminal work in the 1990s put forth a 'work environment hypothesis' that singled out four main factors relating to the occurrence of bullying: work design; leaders' behaviours; the position of the victim; and the organisation's morals or values.

While the language may vary, researchers have used these categories to identify factors that increase the likelihood of bullying. As per the figure below, there are several factors that can put workers at greater risk of experiencing bullying in the workplace; these are related to:

the way work is designed

relationships at work

issues of diversity and inclusion

leadership

the type of worker; and

large-scale organisational factors.

Importantly, while the factors listed above can increase the risk of experiencing or being exposed to bullying, many of them are - particularly when repeated - bullying behaviours in their own right.

Often, a key consideration is delivery. For example, the context in which criticisms are delivered, the way staff are excluded from discussions or decision-making, and the way organisational changes are rolled out are all examples of how individuals' behavioural choices can influence the experience of, and harm caused by, bullying.

As this figure illustrates, while specific actions taken by leaders (for example, restricting engagement) can increase the risk of bullying, the style of leadership adopted by managers and leaders in an organisation can also have a major effect on the risk and experience of bullying.

Individual-level antecedents

A second line of enquiry into bullying antecedents focuses on workers' individual characteristics. In other words, researchers work to identify demographics and personality characteristics or traits that increase the risk of bullying exposure or experience.

In this regard, results from the literature are mixed, with findings influenced by the work context, profession, research methods, and/or geographical location.

the effects and influence of individual antecedents are likely to vary across organizational contexts and between demographic groups...[and] one would also expect that different antecedents may take on different meanings in different settings, and that [individual] factors...would impinge upon such meanings [sic]9.

Gender, ethnicity, disability, and occupation

Some research finds no evidence for differences in gender or sex while other studies indicate the opposite result. Yet other work, however, suggests that, while the cause is unclear, bullied women take more sick leave than their bullied male counterparts, which, in turn, makes the impact of bullying worse and, correspondingly, women are more likely to self-report the experience of being bullied.

Similarly variable results have been found in studies looking at prevalence rates among different ethnicities and age-groups. Generally, older workers and individuals of Māori or Asian descent report a higher incidence of bullying, but whether this is a significant difference depends on the methods used to undertake this research.

New Zealand’s Human Rights Commission recently noted that “Bullying is especially high among disabled workers (52%), bisexual (39%), and Pacific workers (26%)"10, while also delivering results suggesting the risk is higher for those working in specific industries (e.g., retail, hospitality, health care, and arts/recreation services).

Specific occupations have also been highlighted in international research, with workers in roles where they are required to work directly with patients or other clients and/or the public seeing a higher prevalence of bullying.

Some research suggests disabled workers are at higher risk of experiencing workplace bullying; other work reinforces this by suggesting "mental health problems, especially anxiety, are a risk factor of the occurrence of bullying"11, along with physical disabilities and long-term illnesses.

Personality

Studies looking at the link between personality and workplace bullying is similarly mixed.

Some work has identified a correlation between 'negative' emotions and an increased risk of workplace bullying. Such emotions include neuroticism, less locus of control - the perceptions individuals hold about the cause(s) of life events - or lower psychological capital (e.g., hope or motivation).

Other studies suggest "Machiavellianism, openness to experience, [a] sense of coherence...hardiness, psychological detachment, proactive personality...generalised self-efficacy... [and] assertiveness and social anxiety"12 act as a 'buffer' or reduce the impact of bullying.

Interestingly, recent research suggests the reverse may be true as "bullying also may lead to personality changes in exposed individuals".13

Leadership

Researchers have paid particular attention to leadership style as a precursor to workers’ experience of bullying.

Leaders have a direct influence on elements of an organisation’s and team’s culture, as well as elements of work design (e.g., role clarity, limiting control, or approaches to communication) that can have a significant effect on the incidence and, ultimately, effects of, bullying.

In terms of leadership style, research suggests there are two styles that have been strongly associated with workplace bullying: autocratic or authoritarian leadership and 'laissez-faire' or 'hands off' leadership. The latter is associated with a distinct lack of support that provides a condition in which bullying can flourish; some researchers go so far as to suggest a 'laissez-faire' style is a form of bullying in and of itself.

Choosing one of these styles can be a damaging approach as it "perpetuates high-power distance clusters and [increases] bullying behaviours".14

Conversely, a more positive approach, such as transformational, transactional, and supportive leadership, has been shown to act as a 'buffer', mediating some of the negative effects of other organisational factors, and even having a protective effect.

However, it's worth considering that some studies suggest that, even in the presence of positive leadership styles, their effects can be undermined in instances where bullying is occurring between colleagues on the same level in an organisation.

Interactions between antecedents

Of course, while the literature has explored these two different avenues, antecedents are not mutually exclusive; there is nothing to suggest that workers at risk of bullying because of their demographical characteristics are not at greater risk due to organisational factors.

In all likelihood, there are complex interactions between organisation- and individual-level antecedents. This is reflected in findings from research that provide support for both group of antecedents acting as risk factors for exposure to bullying.

One example of such an interaction is the finding that conscientiousness has been shown to be a "significant predictor of later victimization from bullying [sic]", highlighting "the importance of work factors in predicting bullying".15

What are the effects of workplace bullying?

Key to understanding workplace bullying is the harm resulting from bullying behaviours.

More than a decade ago, researchers noted that "exposure to workplace bullying is a 'more crippling and devastating problem for employees than all other kinds of work-related stress put together"16 Despite the antecedents discussed above, multiple studies and reviews highlight these effects are seen regardless of geography or profession.

Importantly, research identifies that, in addition to the victim, workplace bullying has serious implications for witnesses, colleagues, and the wider organisation.

It's important to keep in mind that various issues with the body of research looking into these effects (e.g., research design, sampling limitations etc.) mean that causal relationships between exposure to bullying and these effects cannot be easily identified or generalised.

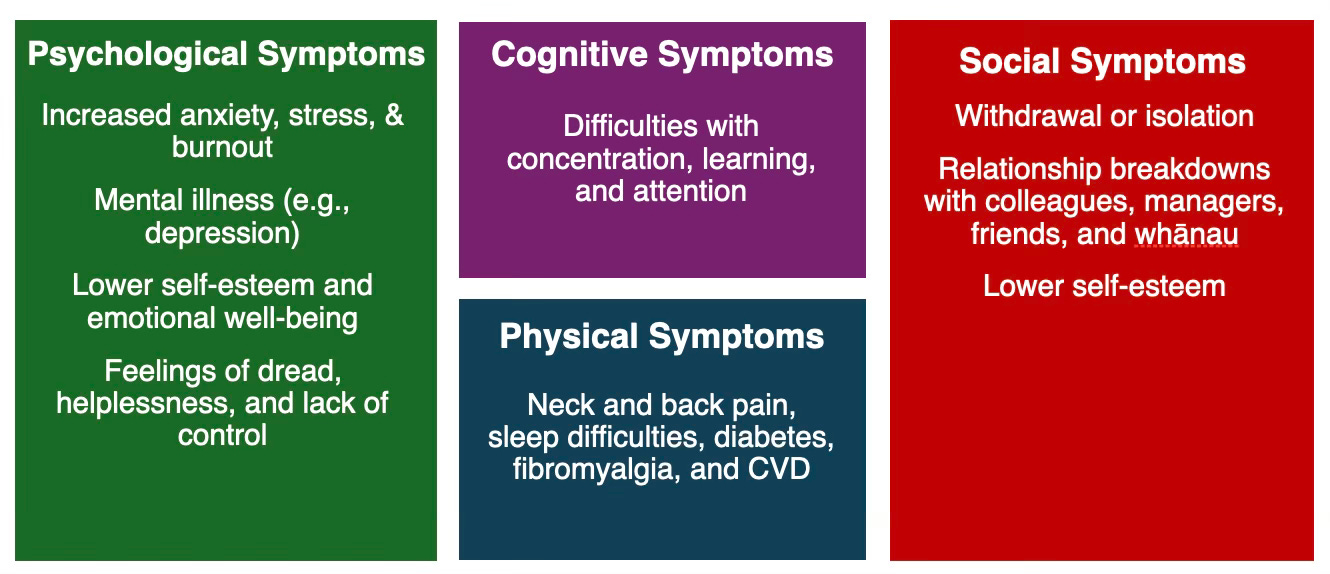

Individual effects

Victims of, and witnesses to, bullying present with a range of physical, psychological, cognitive, and social symptoms.

Psychological symptoms:

Increased anxiety, stress, and burnout.

Serious mental health issues such as depression and suicidal ideation.

Lower self-esteem and emotional well-being.

Feelings of helplessness, dread (around work), and lack of control.

Physical symptoms including (but not limited to):

neck and back pain

sleep difficulties

diabetes

fibromyalgia; and

cardiovascular disease.

Cognitive symptoms, such as difficulties with:

concentration

learning new things; and/or

low attention.

Social symptoms such as:

withdrawal or isolation

low self-esteem; and/or

a breakdown in relationships with colleagues, friends, and whānau.

Alongside these effects on individuals, various sources note other key considerations, including:

"the longer the traumatic events are endured, the more severe…the consequent ill-health effects"17

exposure to workplace bullying can have a generalised effect on an individual’s quality of work life (QWL) - which “can influence job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and determine the ability of employees to cope with their work [sic]” - with research showing an inverse relationship between bullying and QWL

"targets of persistent bullying [have] reported higher levels of psychological strain when they sought...a solution [their emphasis]"18

when people report bullying, research suggests this results in negative experiences continuing, resulting in further harm

Such considerations underscore the importance of businesses or organisations ensuring they take a proactive, quick response to complaints of workplace bullying that leverage proven effective interventions.

While experiences of and witnesses to workplace bullying generally result in negative effects for individuals, it's also worth noting that research into bullying in the health and allied health sectors has found that, for some, the experience of bullying had a positive effect in the form of increased individual resilience.

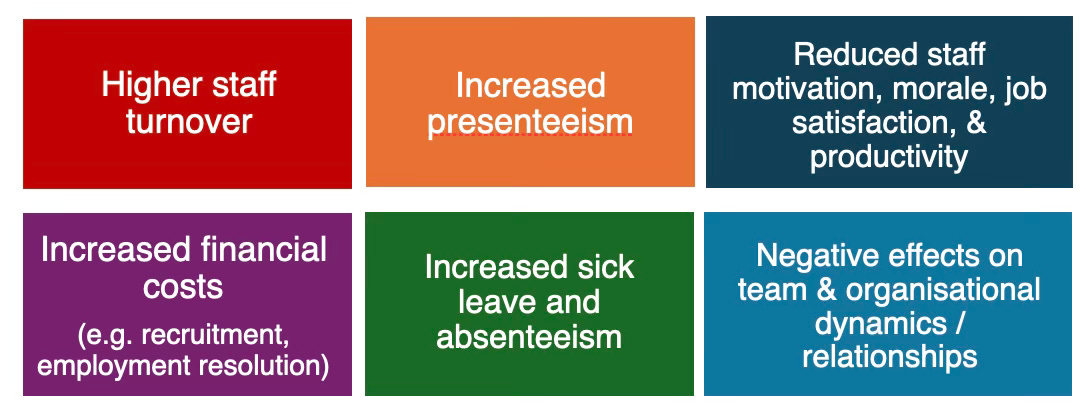

Organisational effects

In addition to effects on individuals, workplace bullying can also affect the organisation in several ways.

Higher rates of sick leave/absenteeism.

Higher rates of presenteeism.

Lower staff motivation, morale, job satisfaction, and productivity.

Higher staff turnover.

Effects on team and organisational dynamics and relationships.

Costs associated with recruitment, retention, and legal/conflict-resolution processes.

While it is not clear what the financial cost of bullying is to workplaces in Aotearoa, "research in Australia estimated it cost businesses there between $7.5-16 billion per year"19

What can workplaces do to address bullying?

Workplace strategies

As with many other health, safety, and well-being risks, to be effective in dealing with workplace bullying, workplaces need to use a combination of strategies that address prevention and effective responses.

To address bullying - and support the mental health and well-being of workers - it is important workplaces focus on three 'levels' of interventions.

Primary - those interventions that tackle bullying at the source (i.e., the factors that give rise to bullying, such as poor leadership).

Secondary - interventions that empower staff to effectively cope with issues.

Tertiary - interventions that provide support to staff once they have been exposed to bullying at work (e.g., EAP support).

This approach reflects a hierarchy of controls proposed by the Government Health and Safety Lead for dealing with similar psychosocial risks.

individual coping strategies alone are likely to be ineffective, reinforcing the need for the organisation to develop primary prevention measures to tackle workplace bullying20

In addition, literature reviews highlight that "managing bullying is likely to be less effective than preventing it"21 in the first place.

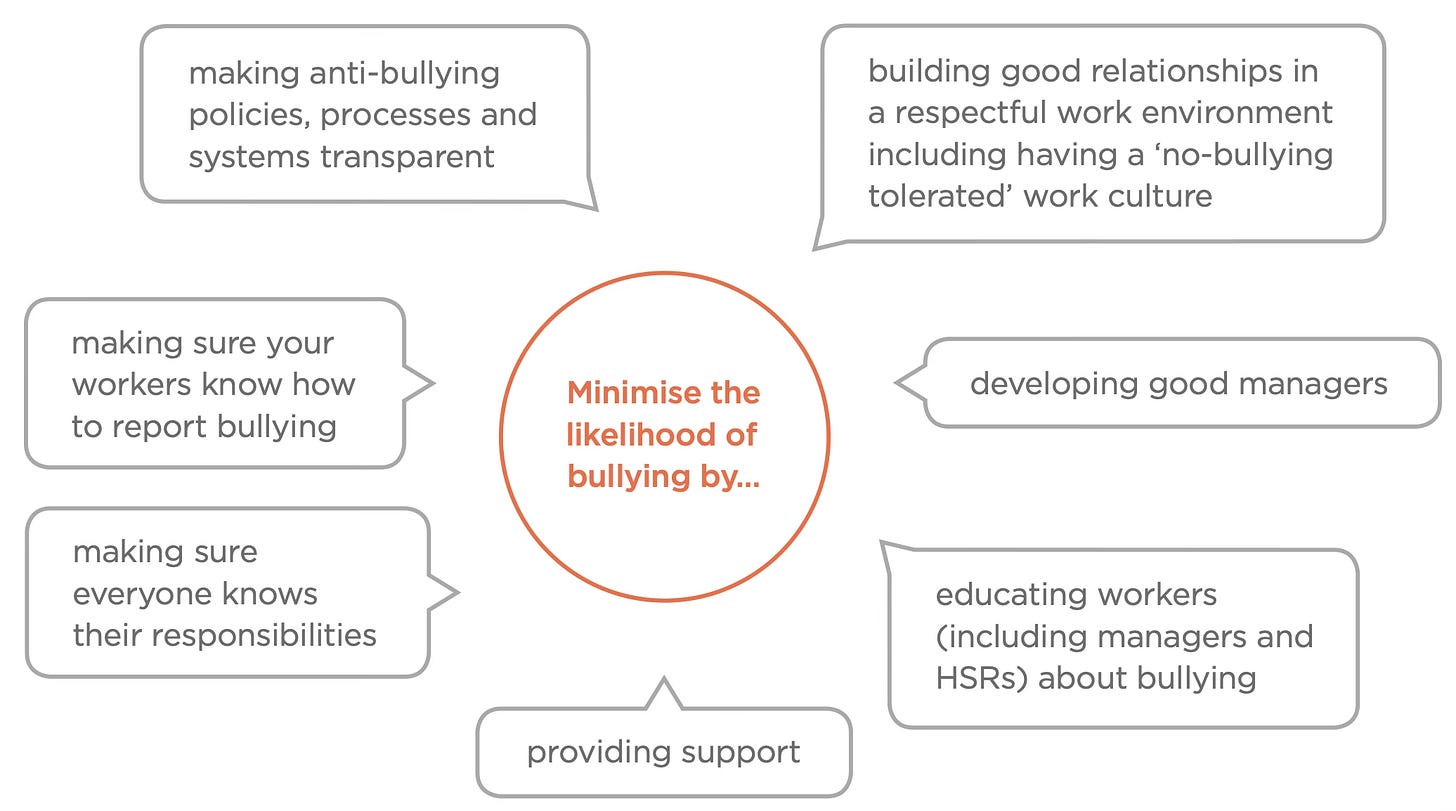

In 2017, WorkSafe updated its guidance for workplaces, identifying seven control measures businesses can implement to reduce the likelihood of bullying in their organisation.

The content below provides further detail on some key interventions, including focussing on work culture; bullying policies; leadership; and organisational responses; these reflect the "four pillars of healthy work" identified by Catley.22

Intervention effectiveness

When selecting strategies, interventions, or control measures to combat workplace bullying, it’s important businesses consider the efficacy of those they choose.

Reviews from the mid-2010s found that interventions introduced to combat workplace bullying had little to no effect on the occurrence of bullying, and what effect they did have was isolated to "knowledge...attitudes, and self-perceptions".23 Others present contrasting findings, while acknowledging the limited availability of studies that robustly examine the efficacy of interventions targeting workplace bullying.

[M]easures to prevent workplace bullying have a positive impact, particularly when they are perceived as being effective. The presence and perceived effectiveness...have been linked to less bullying and to reducing the negative impact on wellbeing and performance [sic]."24

This paucity of research highlights the importance of on-going, robust research, as well as the important practical step of ensuring workplaces continue to review and measure the effectiveness of the interventions they use.

Workplace strategies

Respond effectively

One key step organisations can take to support their employees is to ensure appropriate response mechanisms are in place.

While processes that support workers' ability to report bullying is essential, what is perhaps more critical is a work environment in which all staff feel safe to speak up (i.e., there is a high level of psychological safety or a positive psychosocial safety climate).

Even though definitions of bullying emphasise its repetitive, pattern-based nature, researchers note that processes for investigating and responding to reports should be initiated "even [if they are] one-off incidents that appear insignificant - regardless of whether they constitute bullying or not [my emphasis]".25

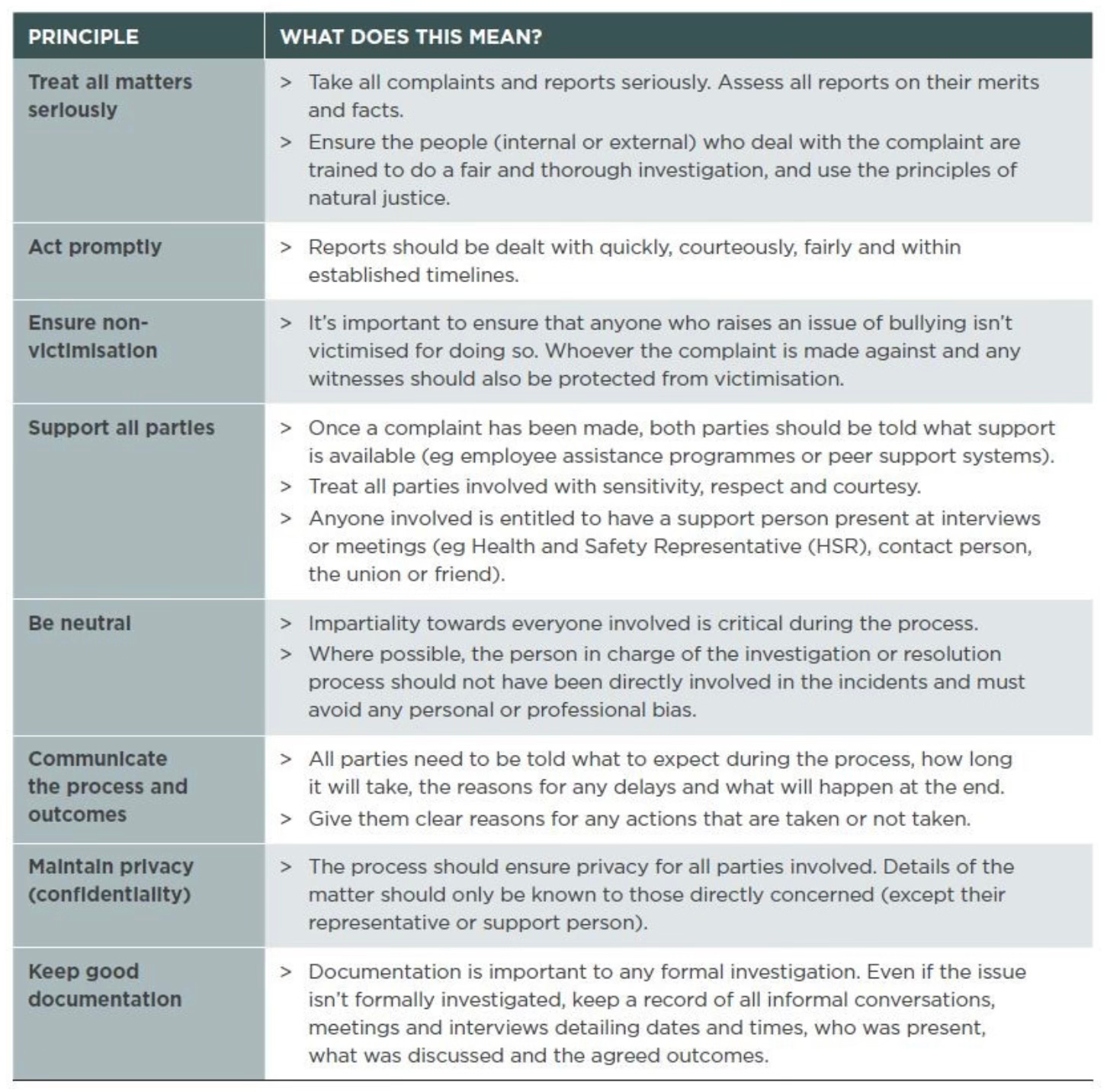

WorkSafe provides useful guidance around the processes and systems needed to deal with bullying (e.g., training, reporting, monitoring, feedback). This includes a set of key principles WorkSafe recommends for workplaces to follow when handling bullying complaints.

Importantly, when investigating reports of bullying, processes need to:

be impartial and fair for all parties

be transparent

be undertaken in a timely fashion

focus on behaviours, rather than personalities; and

include a pathway for processes and practices that will help all involved rebuild potentially damaged relationships.

While we know an effective response that adheres to evidence-based principles is important, research has suggested that those who report bullying often did not see "a cessation in bullying" but, instead, experienced "a continuation of the ill-treatment, further victimisation for making a complaint and leaving the organisation" and "for the majority of those who reported bullying, the issue was not addressed and/or the behaviour continued"26

Alarmingly, research indicates workplaces sometimes engage in behaviours labelled as 'organisational sequestering' in which professionals avoid concerns raised by staff and do not attempt to resolve the issue(s). Catley27 suggests such behaviour can present as:

"reframing - repositioning the concern to make it something else entirely"

"rejigging" - putting in place "surface level solutions that do not address the underlying cause"; or

"rebuffing" - responding by pushing away "an individual's concerns and requests for intervention".

Given the risk of such behaviours, it is essential senior leaders, other managers, and support personnel do what they can to ensure those raising a concern are not harmed further by these types of behaviour.

Under the Employment Relations Act, employers are required to respond to and address complaints regarding bullying and harassment at work as part of their duty of good faith and to provide a safe workplace. When a concern or complaint is raised, the response taken should be impartial, fair to all parties, guided by the rules of natural justice, and take into account the nature of the issue and wishes of the person who raised it [sic].28

This point from MBIE is echoed by other authors, who note that, given bullying "is a serious psychosocial hazard...under current legislation (Health and Safety at Work Act, 2015) employers have an ethical and legal obligation to identify and manage this risk [my emphasis]."29

A common response when an employee reports one or more bullying events is to move the affected staff member (i.e., the person who made the complaint) to a different team, business group, or reporting line. Both the Ministry for Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE) and WorkSafe are clear: this should NOT be the default action taken by businesses.

If the behaviour is not considered serious enough to suspend the person [the complaint is against] while [an] investigation is being done, then it may be appropriate to move the person to another area during the investigation. The complainant shouldn’t be the person moved (unless they specifically want this) as this may look as if they are being punished for being the victim/saying that they are being bullied [my emphasis].30

Timeliness is another important consideration; the earlier bullying behaviours can be 'headed off at the pass', the lower the impact on the parties involved in a given situation. Speaking about the role of incivility as a precursor to bullying, researchers identify it is important to take action "immediately...to avoid conflict escalation, and the subsequent risk of bullying".31

Similarly, a focus on behaviour, rather than personality, is key. In some instances, "victims are blamed as having previous personality disorders to justify their subsequent injuries".32 Because of the resulting harm arising from such actions, it is essential workplaces avoid such judgements.

Focus on work culture

The culture of the organisation is often cited as being key to the effective prevention of and response to bullying.

Organisations need to seek to establish a culture:

where bullying is not tolerated

that can be characterised as a healthy, respectful workplace; and

in which organisational values and behaviours support "a positive communication culture"33

Importantly, even the perception of support provided via a positive work culture can reduce - or, when this is perceived to be lacking, increase - the impact of bullying.

Providing such a culture is a key component of mentally healthy work; this is essential for supporting all workers' mental health and well-being at work and, as such, is a requirement under current legislation in Aotearoa.

There is no point in having interventions if the culture is wrong in the first place.34

Scholars identify the following elements of a positive work culture needed to mitigate the risk of bullying:

having a clear Code of Conduct in place and ensuring all employees understand behavioural expectations

a commitment to making changes when a need to do so is identified

having clear values with supporting guidelines that further define expectations

using, and continuously improving, education and policies

fostering a shared sense of purpose

providing an environment that is psychologically safe

creating an environment that facilitates development and maintenance of positive work relationships; and

recognising and promoting diversity and developing an inclusive, tolerant environment.

Promote positive relationships

Just as poor relationships at work can increase the risk of bullying, positive relationships can go some way to mitigating the effects of bullying.

Consequently, a work culture that facilitates social support and work relationships will support those experiencing, or at risk of, bullying. This is doubly-important when one considers that, when bullying occurs, those at the receiving end are likely to lose some or all social support at work.

Various studies demonstrate the positive effects of support from co-workers, work friends, and other workplace relationships. Such support - particularly emotional support - provides an important resource that can be used to reduce the demands of bulling.

Interestingly, a review undertaken by Farley and colleagues noted that "leadership-specific support showed mixed effects [in research]"35, although other research opposes this position, instead asserting that support from leaders is especially important in reducing risks and subsequent impacts.

Outside of work, studies show non-work relationships can significantly reduce the impact of bullying on victims/targets, while support provided by whānau (family) can act as a 'buffer' between the experience of bullying and burnout.

Build a positive Psychosocial Safety Climate

An important component of work culture is the psychosocial safety climate or PSC. A positive PSC is where:

the workplace is psychologically safe (i.e., workers can ask questions, provide feedback, and suggest improvements without fear of reprisal)

managers and leaders value employee welfare over business outputs or metrics

there are transparent, effective health and safety policies and processes in place; and

there are effective, multi-directional opportunities for engagement with and between staff.

[A negative PSC] is talked about as the 'cause of the causes' of work stress and is the leading psychosocial risk factor at work capable of causing psychological and social harm through its influence on other psychosocial factors.36

A positive PSC has been consistently shown to reduce the impact of bullying on victims, and have also been shown to act as a preventative measure, while negative or low PSC workplaces are associated with a higher incidence of workplace bullying.

In this context, a high level of psychological safety is important as, typically, higher levels of bullying are seen at workplaces where conformity is highly valued and/or rewarded, and where staff engage in behaviours that pressure others to conform. Consequently, to combat this, it's important all leaders promote and reward a culture of speaking up, asking questions, and challenging the status quo in a constructive and respectful way.

Develop robust policies

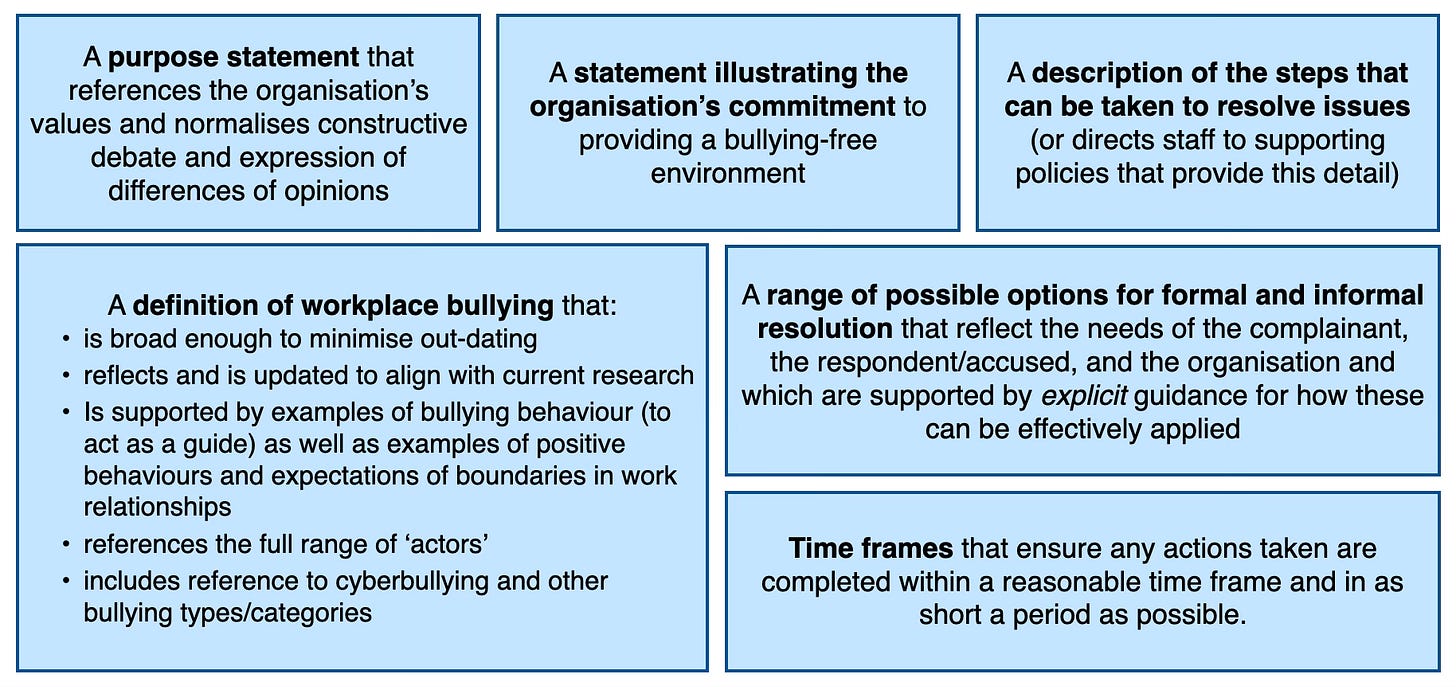

Another key strategy is the development, provision, and continuing review of an appropriate anti-bullying policy.

Authors have identified a number of elements that need to be included in an effective policy.

In addition to the elements highlighted above, others note the importance of ensuring such policies set-out specific roles and responsibilities.

In terms of accessibility, bullying policies need to be written using language that is easy-to-understand (avoiding, wherever possible, 'legalese'), and available in multiple languages and formats; less coherent policies and processes are typically associated with a higher incidence of workplace bullying.

Finally, others argue that bullying policies need to take a wider approach to how bullying is defined.

Policies that only cover matters protected in legislation (e.g., harassment based on race [or] gender) can be used to exclude bullying behaviour that does not meet a legal definition and therefore fail to protect from many other types of bullying.37

Policy implementation and review

Unfortunately, research shows "that, although policies may be well written, they may be poorly implemented"38; this can result in ineffective action or, worse, further harm to those exposed to bullying.

Commentators agree: any such policy needs to be supported by clear processes and resources. This includes providing:

on-going training for new and current staff

'socialisation' processes in which the policy and associated issues are discussed in multiple settings; and

a clear, easy-to-use process for reporting instances of bullying.

As "studies highlight the need for leadership support of, and skill in, implementing a [workplace bullying] policy"39, managers and leaders need to be given an appropriate level of support to ensure they are confident with policy implementation.

A final piece of the puzzle is the need for a robust process for undertaking regular policy reviews. As with initial policy development, these should be undertaken via a lens of both victims and perpetrators, and with input from all stakeholders, including employee representatives (e.g., union Delegates).

Handling complaints - Key principles

WorkSafe has outlined some key principles businesses and organisations need to adopt when they receive reports or complaints from staff about bullying or harassment.

Arguably, given the role instances of incivility may play as a precursor to workplace bullying and their effect on workers' well-being, it may be appropriate for workplaces to consider adopting these principles in all reports - including 'one-off' instances - of inappropriate behaviour.

Some research has noted that "when targets of bullying are perceived as [being] responsible for their situation, they are less likely to receive help from others"40. In particular, if staff are seen or heard to complain about bullying but are then perceived to not actively address the issue, they receive less help from HR professionals and less support from employers and colleagues.

Ignoring reports and/or not treating them seriously is an especially 'slippery slope' as this can increase the harm experienced by those who have experienced or witnessed bullying.

Research also suggests additional biases may be in play.

Perpetrators were afforded leniency from [HR professionals] for failing to make changes because of a (potential) lack of information regarding the situation, but targets who were frightened of or unaware of the procedures for dealing with workplace bullying were definitively less likely to receive help.41

Consequently, it is essential the principles above - including treating all matters seriously, remaining neutral, and supporting all parties - are followed when concerns about bullying are raised. This can be supported by formalised training for those who deal with and respond to bullying complaints.

An additional consideration is ensuring staff have access to individuals who can act as advocates or 'champions' (e.g., HSRs or union Delegates) to support adherence to principles, policies, and processes.

Provide effective leadership

Without effective leadership, policies may be poorly implemented and/or the ability to establish a positive work culture may be severely undermined.

Leaders need to take a hands-on approach to changing organisational culture. This means modelling mentally healthy work behaviours and being held accountable for staff wellbeing [sic].42

Leaders need to work hard to adopt a 'democratic' style (e.g., transformational, transactional, supportive, or authentic leadership) that will reduce the risk of bullying taking place. In addition, leaders "need to act as role models and exhibit open, honest and respectful communication, and lead the establishment of a bully-free culture"43

when leaders communicate clear goals and expectations, involve employees in decision-making, show concern for employee needs and employee development and handle conflicts well, the risk of bullying in the work community drops significantly [sic]44

Social support has been identified as a key strategy for mitigating the risk of harm associated with exposure to workplace bullying. As well as that provided by colleagues and work friends, managers and leaders can act as an important source of social support for workers directly or indirectly affected by workplace bullying.

As some studies highlight that managers’ efforts to address bullying are often ineffectual, organisations need to take appropriate action to ensure managers and leaders are well-supported.

To support managers, WorkSafe suggests organisations should:

seek feedback from team members on leaders’ performance

implement robust performance management practices; and

provide effective, regular training and support to managers and leaders.

Research suggests our awareness of available interventions is very low. Consequently, leaders have a key role to play in raising staff members' awareness and understanding of bullying and the supports available to their employees.

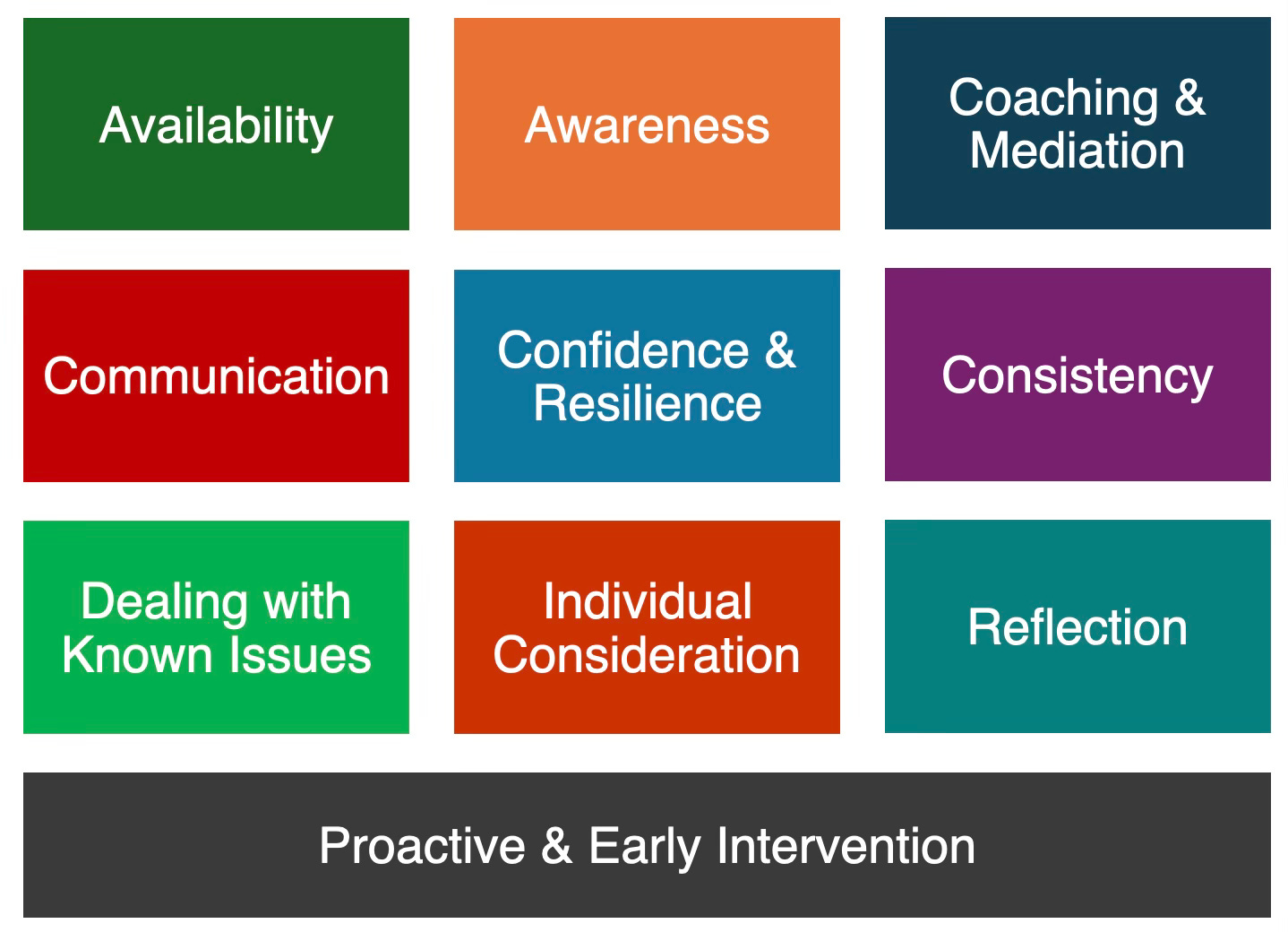

Core leadership competencies

In 2019, local research into the nursing sector identified key management competencies for managing bullying at work.45

Being available to hear staff members' concerns and ensuring staff are heard.

Developing awareness and understanding of bullying and workplace processes.

Providing coaching and guidance, facilitating discussions, and applying questioning skills in an unbiased way.

Modelling clear, transparent communication and facilitating communication between team members.

Having the confidence and resilience to deal with issues as and when they arise.

Ensuring consistency when managing complaints, issues, and investigations, and applying a consistent approach to how behaviours are addressed.

Dealing with known issues by taking a solutions-focussed approach, taking responsibility for bullying, and dealing with any existing issues.

Showing individuals consideration by demonstrating empathy, sensitivity, and validating behaviours when responding to issues.

Being proactive by taking early and immediate action, and demonstrating situational awareness.

Engaging in self-reflection, understanding their own limits, and knowing when and how to seek support.

Many of these competencies align with the key principles for responding to bullying recommended by WorkSafe.

Importantly - as with all responses to concerns raised by staff around bullying, incivility, and other inappropriate behaviour - timeliness is key. As the nursing report from Blackwood and colleagues notes, these competencies "are more likely to be effective at the early stages of a bullying episode".46

Another consideration is an awareness that there are a number of other factors that influence the effectiveness of these competencies and managers' ability to apply/demonstrate them. These include:

Team factors, such as the number of people in the team.

Organisational factors, such as existing policies and processes, work culture, and support provided for managers.

Industry factors, such as funding.

Other factors, such as managers' workload, the individual characteristics of the parties involved, or managers' own experience of bullying.

Finally, while the importance of leaders in preventing and responding to bullying, and providing support for victims and witnesses is beyond contestation, it's important workplaces take a multi-pronged approach, applying many different primary, secondary, and tertiary interventions.

Where can you get help?

There are a number of avenues available if you or someone you know is experiencing or is witness to workplace bullying.

Useful sites

Helplines

Lifeline - 0800 543 354

Depression Helpline - 0800 111 757

Healthline - 0800 611 116

Need to Talk - 1737

Bibliography

Bentley, T. A., Catley, B., Cooper-Thomas, H., Gardner, D., O'Driscoll, M. P., Dale, A., & Trenberth, L. (2012). "Perceptions of workplace bullying in the New Zealand travel industry: Prevalence and management strategies". Tourism Management, 33(2), 351–360.

Blomberg, S., and Rosander, M. (2022). "When do Poor Health Increase the Risk of Subsequent Workplace Bullying? The Dangers of Low or Absent Leadership Support". European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(4), 485-495.

Bone, K., and Gardner, D. (2022). "Organisational Culture for Psychological Health at Work". In WorkSafe (Eds) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand: Short Essays on Important Topics, (pp.143-157). WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

Blackwood, K., D'Souza, N., and Sun, J. (2019). Understanding Management Competencies for Managing Bullying and Fostering Healthy Work in Nursing. Healthy Work Group, Massey University: Auckland.

Business Leaders' Health and Safety Forum (2023). Psychological Safety. Business Leaders' Health and Safety Forum: Wellington, NZ.

Catley, B. (2022). "Workplace Bullying in New Zealand: A Review of the Research". In WorkSafe (Eds) Mentally Healthy Work in Aotearoa New Zealand: Short Essays on Important Topics, (pp.172-217). WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

Elazzazy, O. M. (2023). “The Moderating Role of Workplace Social Support In The Relationship Between Workplace Bullying and Job Performance.” Journal of System and Management Sciences, 13(2), 529-542.

Employment New Zealand (2024). General Process: Preventing and Dealing with Bullying, Harassment and Discrimination. MBIE: Wellington, NZ.

Farley, S., Mokhtar, D., Ng, K., and Niven, K. (2023). "What Influences the Relationship Between Workplace Bullying and Employee Well-being? A Systematic Review of Moderators". Work & Stress, 37(3), 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2023.2169968

Feijó FR, Gräf DD, Pearce N, Fassa AG. (2019). "Risk Factors for Workplace Bullying: A Systematic Review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(11):1945. doi: 10.3390/ ijerph16111945

Field, E. M. and Ferris, P. (2021). "Diagnosis and Treatment: Repairing Injuries Caused by Workplace Bullying". In P. D'Cruz, E. Noronha, C. Caponecchia, J. Escartín, D. Salin, and M. R. Tuckey (Eds) Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse, and Harassment: Dignity and Inclusion at Work (pp. 231-264). Springer: Singapore.

Ferris, P. A., Deakin, R., & Mathieson, S. (2021). “Workplace Bullying Policies: A Review of Best Practices and Research on Effectiveness.” In D'Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Caponecchia, C., Escartín, J., Salin, D., & Tuckey, M. R. (Eds). Dignity and Inclusion at Work, pp.59-84.

Goh, H. S., Hosier, S., and Zhang, H. (2022). "Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses - A Summary of Reviews". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8256).

Government Health and Safety Lead (2021, May). Creating Mentally Healthy Work and Workplaces: A Guide for Public Sector Health and Safety Leaders and Practitioners. Government Health and Safety Lead: Wellington, NZ.

Government Health and Safety Lead (2022, June). Mentally Healthy Work 101. Government Health and Safety Lead: Wellington, NZ.

Hodgins, M., MacCurtain, S. and Mannix-McNamara, P. (2020), "Power and inaction: why organizations fail to address workplace bullying", International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 13(3), pp. 265-290.

Holm, K., Torkelson, E. & Bäckström, M. (2022). "Workplace Incivility as a Risk Factor for Workplace Bullying and Psychological Well-being: A Longitudinal Study of Targets and Bystanders in a Sample of Swedish Engineers". BMC Psychol, 10, 299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00996-1

Khieu, T., Hannah, T., and Mohammed, K. A. (2022). New Zealand Psychosocial Survey 2021. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

Marlowe, C., Ang, H. B., and Akhtaruzzaman, M. (2021). "The Long- Term Effects of Workplace Bullying on Health, Wellbeing, and on the Professional and Personal Lives of Bully-victims". New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 46(2), 31-51

Massey University (2023, May 18). Higher Frequency Bullying Remains Significant in Workforce.

Mental Health Foundation (n.d.). Fact Sheet: About Workplace Bullying. Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand: Auckland, NZ.

Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (2020). Summary Issues Paper: Bullying and Harassment at Work.

Namie, G. (2021). 2021 WBI U.S. Workplace Bullying Survey. Workplace Bullying Institute: Clarkston, WA.

New Zealand Human Rights Commission. (2022). Experiences of Workplace Bullying and Harassment in Aotearoa New Zealand. Human Rights Commission: Wellington, NZ.

Nielsen, M. B. and Einarsen, S. V. (2018). "What we Know, What we do not Know, and What we Should and Could have Known about Workplace Bullying: An Overview of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research". Aggression and Violent Behavior, 42, pp. 71-83.

Rae, K. and Neall, A. M. (2022). "Human Resource Professionals' Responses to Workplace Bullying". Societies, 12(6), 190.

Raypole, C. (2019, April 29). How to Identify and Manage Workplace Bullying.

Salin, D. and Hoel, H. (2020). "Organizational Risk Factors of Workplace Bullying". In S. V. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, and C. L. Cooper (Eds) Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace (3rd Edition) (pp. 305-329). CRC Press: FL, US.

Stanley, N. (2019, July 22). Getting to the Bottom of New Zealand Workplace Bullying.

Umbrella (2023, June 20). Understanding and Dealing with Workplace Bullying.

Wilson, C. R. (2021, December 18). Bullying in the Workplace: 24 Examples and Ideas for Supporting Adults.

WorkSafe New Zealand (2017, March). Preventing and Responding to Bullying at Work: Guidelines for Persons Conducting a Business or Undertaking. WorkSafe: Wellington, New Zealand.

WorkSafe (2017). Bullying at Work: Advice for Workers. WorkSafe New Zealand: Wellington, NZ.

Zulkarnain, Z., Ginting, E. D. J., Novliadi, F., & Pasaribu, S. P. (2023). “Workplace Bullying and its Impact on Quality of Work Life”. KONTAKT-Journal of Nursing & Social Sciences related to Health & Illness, 25(1), 385-390

WorkSafe (2017, p.8).

Marlowe, Ang, and Akhtaruzzaman (2021, p.34).

Holm, Torkelson, & Bäckström (2022, p.2).

Mental Health Foundation (n.d., p.2).

Hodgins, MacCurtain, & Mannix-McNamara (2020, p.270).

New Zealand Human Rights Commission (2022, p.33).

Ibid, p.40.

Hodgins et al. (2020, p.266).

Salin & Hoel (2020, p.321).

New Zealand Human Rights Commission (2022, p.34).

Blomberg & Rosander (2022, p.486).

Farley, Mokhtar, Ng, & Niven (2023, p.13).

Blomberg & Rosander (2022, p.486).

Goh, Hosier, & Zhang (2022, p.16).

Nielsen & Einarsen (2018, p.74).

Bentley et al. (2012, p.351).

Marlowe, Ang, & Akhtaruzzaman (2021, p.34).

Farley, Mokhtar, Ng, & Niven (2023, p.14).

Stanley (2019, p.2).

Bentley et al. (2012, p.358).

Farley, Mokhtar, Ng, & Niven (2023, p.18).

Catley (2022, p.202).

Nielsen & Einarsen (2018, p.76).

Catley (2022, p.195).

Stanley (2019, p.3).

Catley (2022, p.203)

Ibid, p.204.

MBIE (2020, pp.7-8).

Blackwood, D’Souza, & Sun (2019, p.1).

Employment New Zealand (2024).

Holm, Torkelson, & Bäckström (2022, p.11).

Field & Ferris (2021, p.5).

Wilson (2021, p.3).

Marlowe, Ang, & Akhtaruzzaman (2021, p.36).

Farley, Mokhtar, Ng, & Niven (2023, p.15).

GHSL (2022, p.3).

Hodgins et al. (2020, p.274).

Ferris, Deakin, & Mathieson (2018, p.15).

Ibid, p.16.

Rae & Neall (2022, p.2).

Ibid, p.10.

Bone & Gardner (2022, p.X).

Bentley et al. (2012, p.358).

Salin & Hoel (2020, p.313).

Blackwood, D’Souza, and Sun (2019, p.14).

Ibid, p.13.